From the

New York Review of Books, "How They Stopped Slavery: A New Perspective, David Brion Davis, by 6 June 2013 --

While historians have long countered the myth that slavery was not the central cause of the Civil War, they have clung to the view that the Union’s opposition to slavery developed very slowly and almost reluctantly, largely due to the Republicans’ commitment to the constitutional ban on “interference” with slavery that already existed in slaveholding states. Hence Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation often appears as a sudden, radical action, really out of the blue. Though I long accepted most such interpretations, I have always been puzzled by the so-called First and Second Confiscation Acts, passed by Congress in 1861 and 1862, which have received far too little attention. These acts applied, among others, to armies fighting in the South, to whom slaves might surrender. The 1861 act, for example, held that Confederate properties including slaves were the “lawful subject of prize and capture wherever found.”

Fortunately James Oakes’s Freedom National clarifies the aims of the war with a wholly new perspective. I agree with the eminent historians Eric Foner and James M. McPherson that his book (in Foner’s words) is “the best account ever written of the complex historical process known as emancipation,” though for some reason Oakes omits the complex French and British responses to the Civil War, including the close decision not to intervene and formally recognize the Confederacy.1 But Oakes shows how President Lincoln and other Republican leaders experienced “memory lapse[s]” that contributed to myths that obscured the meaning and impact of the two Confiscation Acts, that portrayed Lincoln as a “reluctant emancipator,” and that erased much of the history of emancipation before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863.

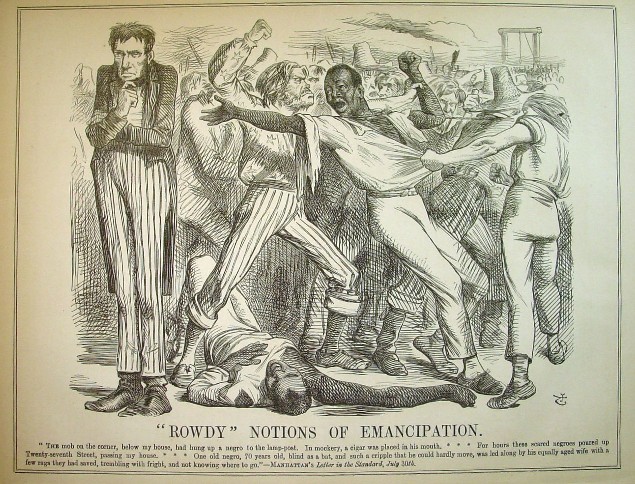

Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865; by James Oakes

The basic theme of Oakes’s long and extremely detailed book is that Lincoln’s new Republican Party was a strong and united antislavery party both before and throughout the war, a party dedicated to the proposition that defining humans as chattel property was a violation of the “freedom principle” embodied in natural and international law. Republicans held that such chattel bondage was unrecognized in the US Constitution, which defined slaves as “persons held in service,” not property, and was thus restricted within the boundaries of specific Southern states whose laws sanctioned true slavery.

This was the meaning of the slogan “Freedom National, Slavery Sectional,” terms used by the abolitionist Charles Sumner not long after he was elected to the Senate in 1851, terms that extended back to the pivotal British Somerset ruling of 1772, which held that “no master ever was allowed here to take a slave by force to be sold abroad because he had deserted from his service, or for any other reason whatever.” The terms also extended back to the natural condition of the populations of Western Europe.

Oakes shows that Republicans had devised well-considered plans for a national assault on slavery, that Southerners were quite right in seeing the Republicans as a threat to their “peculiar institution,” and that secession was not a paranoid act of irrationality. But while Republicans were determined from the first to move toward the ultimate extinction of slavery, they could never imagine that their efforts would result in four years of brutal war, at a cost of 750,000 military lives, in order to free four million slaves and permanently outlaw the institution with a ratified constitutional amendment eight months after the assassination of President Lincoln. Oakes succeeds in dramatizing the extraordinary complexity and difficulty of achieving that objective.

Oakes is so absorbed in the Republican Party’s prosecution of the war that he never takes notice of the actual nature of American slavery as experienced by slaves and never recognizes the economic strength and profitability of the institution, which presented one of the major obstacles to abolition, especially since Republican leaders believed that slavery was weak, vulnerable, and obsolete. (Their party had been founded in 1854 to oppose the extension of slavery into Kansas and Nebraska.)

But Oakes convincingly shows that by 1861 Republicans had drawn on the antislavery arguments of such figures as John Quincy Adams, Salmon Chase, Theodore Weld, Joshua Giddings, and Charles Sumner to formulate plans for undermining and attacking slavery, while still observing the “federal consensus” that the Constitution put slavery in the states beyond the reach of federal power. Republican policymakers found a solution to this conundrum in the conviction that, contrary to the Dred Scott decision of 1857, the legality of defining slaves as property was wholly confined to the existing slaveholding states, and could thus be kept from expanding into American territories or the high seas.

The Republicans’ first conception of their aims was based on a theory of containment: “a cordon of freedom” would stop the spread of slavery, a view that went back to abolitionist proposals of the 1830s and the later Free Soil Party. Actually, as early as 1784 Thomas Jefferson sponsored a narrowly failed provision in a bill in the Continental Congress to prevent “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes” from expanding into any of the western territories, even those west of Georgia and the Carolinas.

Oakes fails to mention this but notes that Jefferson’s words were incorporated into the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 banning slavery north of the Ohio River (passed when Jefferson was in France), and then into a Republican bill of 1862 banning slavery “in all places whatsoever where the national Government has exclusive jurisdiction,” including the territories taken over by the Union forces. Finally, Jefferson’s words were incorporated into the Thirteenth Amendment.

Apart from advocating the confinement of slavery to the existing slaveholding states, abolitionists had called for constructing a moral wall or cordon around the slave states in order to undermine even the slaveholders’ support of a condemned institution. As the young escaped slave Frederick Douglass put it in a speech to a large audience in London in May 1846:

I want the slave holder surrounded, as by a wall of anti-slavery fire, so that he may see the condemnation of himself and his system glaring down in letters of light. I want him to feel that he has no sympathy in England, Scotland, or Ireland; that he has none in Canada, none in Mexico, none among the poor wild Indians…. I would have condemnation blaze down upon him in every direction, till, stunned and overwhelmed with shame and confusion, he is compelled to let go the grasp he holds upon the persons of his victims, and restore them to their long-standing rights. (Loud cheers.)2

As Oakes points out, with the Republicans’ political victory in 1860, the cordon became more physical and material. Then the secession of eleven slave states enabled Republicans to abolish slavery in the nation’s capital, ban slavery from the western territories, refuse to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act, and withdraw federal protection from slavery on the high seas. No less important, they applied pressure on the “loyal,” slaveholding border states—Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, which were soon occupied by many Union troops—to abolish slavery on their own. And by early 1862, they required a new state, West Virginia, to abolish slavery as a condition for admission to the Union. That would become a precedent that would later be applied to all states wanting readmission to the Union.

The second abolitionist plan held that in the event of war or rebellion, the federal government could free slaves by “military necessity,” as finally exemplified by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. Here the Republicans drew heavily on two sources of legal argument. First, the case John Quincy Adams had made against the so-called gag rule—which was passed with the support of Southern congressmen in 1836 and barred discussion of slavery in the House until the rule was repealed in 1844. The second argument recalled Adams’s defense of the right of self-emancipation of the African slaves on board the slave ship Amistad in 1839. Indeed, after the abolitionist Charles Sumner learned of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, he waved copies of Adams’s speeches in President Lincoln’s face, defying him to live up to Adams’s arguments. But Oakes makes it clear that Lincoln did not lag behind the Republicans in Congress with regard to antislavery policy. Rather, while one branch of government would sometimes take the lead, they worked together, as can be seen in the enforcement of the First Confiscation Act, which was above all a response to the expected move toward liberty by many of the slaves themselves.

Even before the war, many Republican leaders predicted that in the event of war slaves would flee their masters or possibly rise in a Haitian-like rebellion. But even after the war began, there were no formulated plans for runaway slaves who arrived at the Union-controlled Fort Pickens, in Florida, and were then returned to their masters, right after Lincoln’s inaugural.

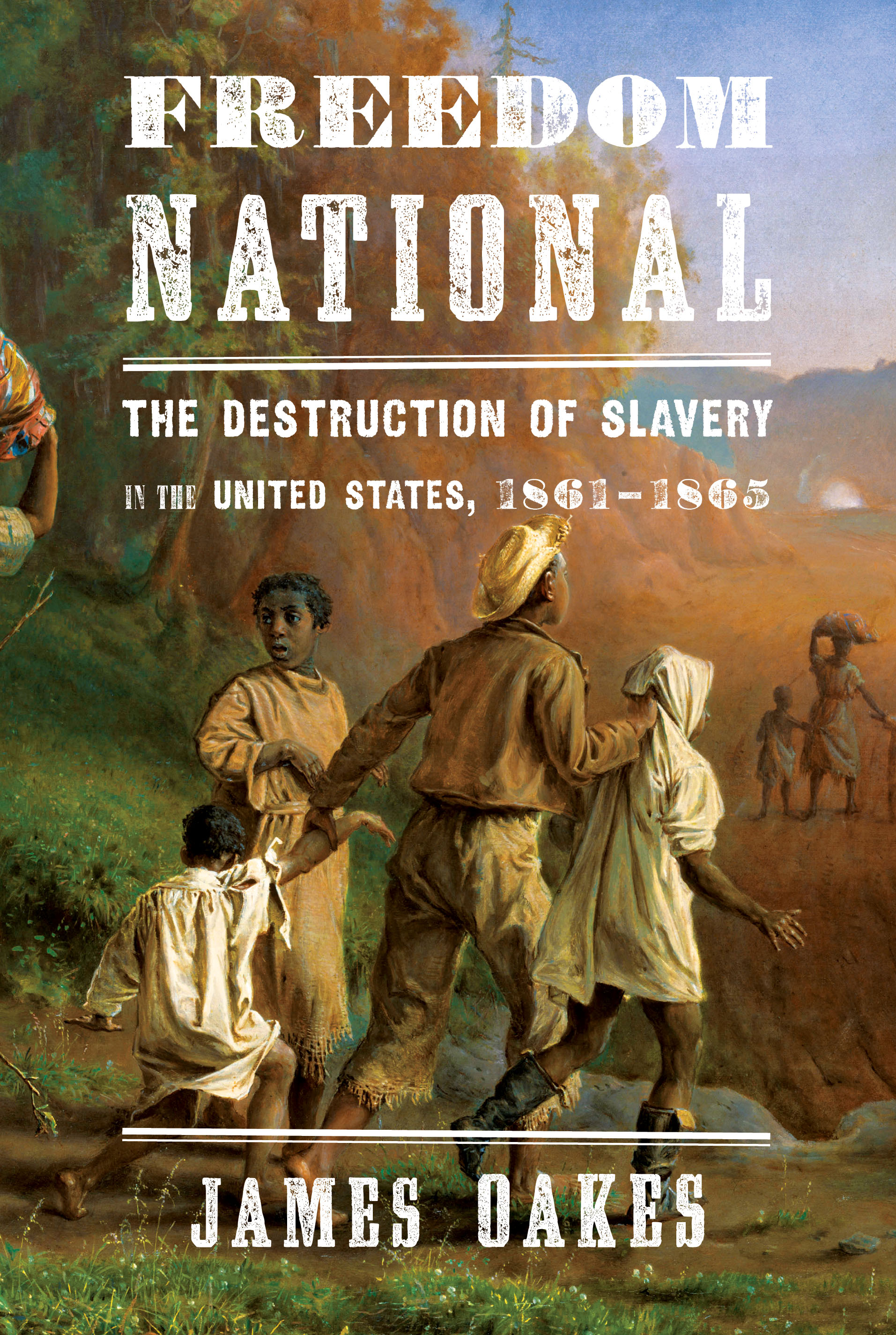

The new policy proclaimed by the Confiscation Acts, based on “military necessity,” began in May 1861 when three slaves fled behind Union lines at Fortress Monroe, Virginia—to be followed by some nine hundred by the end of July. General Benjamin Butler found that the owner of the three fugitives had intended to take them to North Carolina to help secessionists there, and thus sent a report to Washington arguing that slaves should not be returned to aid the rebel cause. The secretary of war and Lincoln’s cabinet approved Butler’s “contraband policy,” allowing able-bodied black men and women to work for wages to support the Union army and to live with their children behind Union lines.

Nevertheless, the Republican leaders agreed that they had to try to balance measures justified by military necessity with the “federal consensus” that the Constitution prohibited direct federal “interference” with slavery in existing states. This goal was reinforced by the crucial need to prevent the slaveholding border states from joining the Confederacy. Thus the War Department’s initial instructions for implementing the First Confiscation Act prohibited Union soldiers from “enticing” slaves away from peaceful farms and plantations. This rule was only overturned by Lincoln, acting as commander in chief of the military, in the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863.

The War Department took a far more radical step in its instructions of August 8, 1861, declaring that the slaves, or rather “persons,” who escaped even from masters “loyal” to the Union would be emancipated. Early in this war against so-called Southern “traitors,” Northern leaders greatly overestimated the number of Southerners who it was hoped would turn out to be loyal to the Union. While the distinction between loyal and disloyal with regard to the freeing of slaves was intended to reinforce such loyal support of the Union, it almost immediately proved to be impossible to carry out.

By July the number of slaves escaping from Confederate territory had convinced Republican leaders that the rebellion of slaveholders had made slavery’s destruction inevitable. While the First Confiscation Act was originally intended to apply only to those fugitives “employed in hostility to the United States,” under the War Department’s instructions “military necessity” meant the freeing of all slaves who voluntarily entered Union lines from any Confederate state. In theory, owners who were loyal to the United States might someday be compensated, but no freed people were to be reenslaved. The act even emancipated the large number of slaves, as in coastal South Carolina, whose masters were presumed to be traitors to the Union since they ran inland from advancing Union troops.

Even though there was some inconsistency in the behavior of Union officers, the First Confiscation Act applied to all parts of the Confederacy occupied by Union troops and within a year of passage it had liberated tens of thousands of slaves. As Oakes emphasizes, it is difficult to imagine how emancipation could have begun any sooner. Contrary to the views of many historians, Lincoln had been informed of every step taken and seems to have accepted the War Department’s more radical criteria for enforcing the law. Yet Oakes never explains why an administration so committed to slave emancipation utterly failed to convey this message to Britain, where supporters of the North desperately needed such news to counteract their powerful enemies.

While the two scenarios, “military necessity” and “cordon of freedom,” were pursued simultaneously, the border states presented unexpected problems of combining them, since internal state struggles between unionists and secessionists coincided with Civil War battles and the partial occupation by Union troops. Lincoln’s urgent need and desire to keep the states within the Union conflicted with his efforts to persuade them, beginning with Delaware, to accept a plan for the gradual, compensated abolition of slavery (as it turned out, Delaware and Kentucky resisted abolition until the very end).

The desire to free the thousands of runaway slaves, many of them crossing over from Confederate states, was enhanced by the fact that they often provided Northern troops with important military intelligence regarding the location of rebel forces. In view of the great complexities, Union generals were divided on the issue of slave masters in the border states who were loyal to the Union. As it turned out, in March 1862 Congress passed and Lincoln signed a law prohibiting the military from enforcing the fugitive slave clause, and a few months later the Second Confiscation Act went further in limiting any enforcement to local civil and judicial authorities in the border states. The army was barred from trying to find whether a fugitive had escaped from a master loyal to the Union cause.

In early 1862 Union troops began to occupy extremely prosperous areas of Louisiana and the lower Mississippi Valley that contained hundreds of thousands of slaves, which gave added impetus to the Republicans pushing for a Second Confiscation Act, or “the emancipation bill,” as it was frequently called. Introduced in early December 1861, this complex measure took over seven months to become law—it was signed by Lincoln on July 17, 1862. Greatly expanding “military emancipation” under the war powers clause of the Constitution, the law aimed at completely destroying slavery in the seceded states, thus abandoning hope of encouraging unionist sentiment in the South. Denying the Southerners any property rights in slaves, it directly emancipated rebel-owned slaves within Union lines in the seceded states, including thousands of slaves in the occupied Mississippi Valley. But especially controversial and the subject of much Republican debate was the section of the act that gave the commander in chief latitude in enforcing a radical clause designed to emancipate slaves in all unoccupied areas of the Confederacy by means of a presidential proclamation.

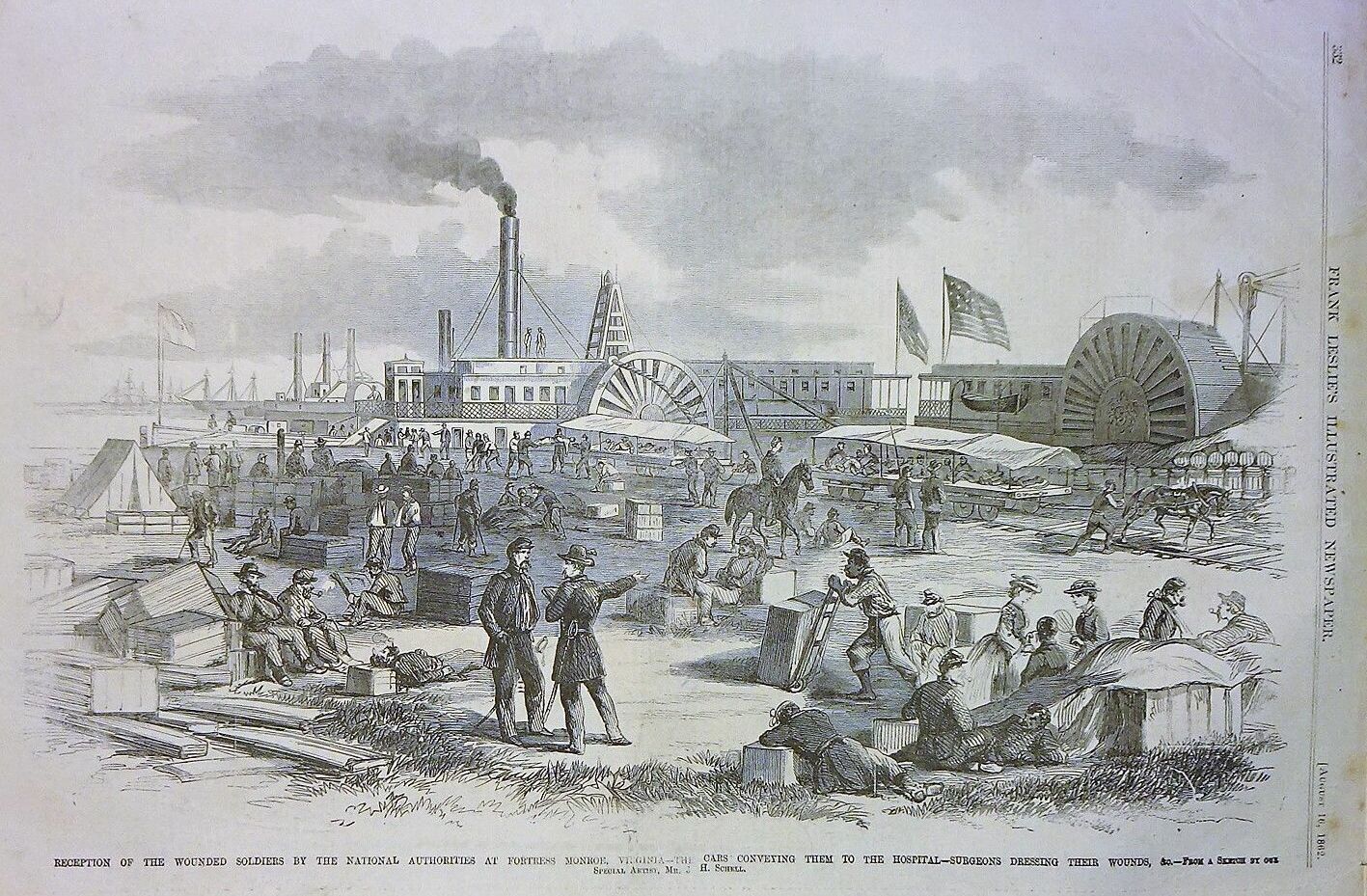

In effect, the Second Confiscation Act authorized and called upon Lincoln to issue a proclamation freeing all rebel-owned slaves in areas not yet occupied by Union forces. Lincoln acknowledged this by quoting verbatim Section 6 of the act in his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of September 22, 1862. Lincoln was troubled by the act’s complicated rules governing the confiscation of rebel real estate, but not by the provisions for emancipation and the enlistment of blacks in the Union army. While the act still distinguished masters who were loyal and disloyal to the Union, the distinction broke down almost immediately as Union generals attempted to recruit former slaves to work in a free labor system, which, as General Benjamin Butler later reassured Lincoln, was working admirably. Of course Democratic and border state congressmen were outraged by the success of the act, and proclaimed that Republican fanatics had destroyed all prospects of restoring the Union and were replaying the themes of the French and Haitian revolutions.

Oakes refutes the myth that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 did not free a single slave as well as the myth that it shifted the purpose of the war from the restoration of the Union to the abolition of slavery (the war to restore the Union had always been a conflict over slavery). He also highlights other aspects of the Emancipation Proclamation, such as the importance of recruiting 180,000 black troops to join the Union army, which became indispensable for a Union victory. The Proclamation not only converted the Union army into a true army of liberation but helped lift the ban on the “enticement” of slaves, so that countless Union soldiers coaxed slaves to leave and spread word of the Proclamation. Union troops even delivered talks on plantations, reducing fears of the consequences of flight and adding to the huge numbers of blacks who followed invading Union forces. Above all, the Proclamation gradually helped convince a large number of voters that total slave emancipation was a necessary condition for the restoration of the Union, a prerequisite for passage and ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Yet as Oakes makes clear, military emancipation could never free most of the slaves in the South, and the Union army could hardly deal with the tens of thousands who flocked behind its lines. Of the nearly four million slaves in the South in 1860, no more than 14 percent of those in the eleven Confederate states had been freed by the war’s end (approximately 474,000 in the Confederate states and another 50,000 in the border states). Lincoln and Republican leaders long expressed faith in both military emancipation and the effects of a “cordon of freedom,” especially for border states, but the Union’s major but very costly military victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863 showed that the war might end without any assurance that even many of the emancipated blacks would not be reenslaved. How could Lincoln guarantee his proclamation that freed slaves would be “forever free” when Confederate leaders promised they would be reenslaved after the war?

Among the barriers or obstacles to full emancipation, Oakes never gives adequate attention to the deeply rooted national white prejudice and fear of African-Americans. While he briefly discusses colonization, especially with respect to Lincoln, he never deals with the broad white consensus, going back to the eighteenth century, that slavery could never be abolished without some plan for “colonizing” freed blacks outside the United States. In considering the costs of emancipation, Oakes also fails to consider the impact on freed blacks of malnutrition and poverty, to say nothing of the outbreaks of dysentery, smallpox, and fever that decimated both Union and Confederate ranks. The Union government gave little thought to what would happen to blacks—where they would go, what they would eat, in a war zone devastated by disease.3

The obstacle that Oakes does stress was the Confederate leaders’ determination to preserve and expand slavery—including extraordinarily harsh efforts to prevent slaves from escaping. It became increasingly clear that even if defeated, the Southerners would do all they could to reenslave the blacks freed by war. In other words, Republicans began to see that military emancipation, despite its great human costs, could never permanently destroy the slave system. After considering various other proposals, including a postwar reduction of the Confederate states to the status of territories, in 1864 Republicans arrived at a consensus that the full and permanent destruction of slavery would require a thirteenth amendment to the Constitution.

Such a radical step required a revised view of the Founding Fathers, who, while intending to promote the eventual ending of slavery, were now seen as making the serious mistake of giving states control of the institution—“the federal consensus.” This control by the Southern states opened the way for the Southern slave power to sponsor the expansion of slavery and bring on the Civil War. Nevertheless, Republicans were careful to bow down to the Founders by linking the wording of the Thirteenth Amendment, which now reached directly into the states, to Jefferson’s wording in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which had been readopted by the First Congress. Of course the Democrats attacked the measure as an “unconstitutional constitutional amendment” and, branding the Republicans as “traitors,” “Jacobins,” and “negro-worshippers,” accused them of launching a tyrannical assault on limited government and states’ rights.

I was surprised to find from Oakes’s account that the Northern Democrats were making a full-scale defense of slavery as late as June 1864. For one prominent New York Democrat, the Thirteenth Amendment would, by “obliterating” the right of states to have slaves, “alter the whole structure and theory of government by changing the basis upon which it rests.” More concretely, by making abolition a precondition for peace, the fanatical Republicans were supposedly destroying the possibility of a negotiated settlement and thus ensuring “eternal disunion and a continuous war.”

Since the Republicans dominated the Senate in June 1864, they easily approved the Thirteenth Amendment 38–6. But on June 15 Democrats won the necessary one third of votes in the House of Representatives to block the measure, to the dismay of the Republicans. Although Lincoln and Republican leaders continued to count on the amendment’s future passage, its defeat in the House heightened the temporary importance of state abolition, which, like military emancipation, was having limited success. By the end of 1864 Maryland, Louisiana, and Arkansas—a border, southern, and western state—had adopted immediate abolition. But failed efforts in Delaware, Florida, and Kentucky signified the limits of the “cordon” ideal. The true destruction of American slavery, it appeared, would largely depend on the outcome of the election of November 1864.

For a time Lincoln himself seriously doubted whether he could defeat his opponent, the almost proslavery Democrat General George B. McClellan, and even moderate Republicans expressed anxiety over prolonging the war and a wish for negotiated peace. But General William Tecumseh Sherman’s spectacular defeat of the Confederates at Atlanta in September 1864 and his subsequent “march to the sea” heightened the prospects of Union victory. In November the Republicans regained more than enough seats in the House of Representatives to secure passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in the Thirty-Ninth Congress the following year. Lincoln announced that if the amendment failed again in the next meeting of the Thirty-Eighth Congress, he would call the Thirty-Ninth Congress into special session in July 1865. But as it turned out, that would be months after Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, and the end of the war. Lincoln and Republican leaders realized that the war itself provided a major justification for the amendment—the suppression of slaveholder rebellion.

As a result, when the congressional debate began in January, and the Democrats seemed unmovable, Lincoln and his associates saw the need for the intense lobbying campaign dramatized in the recent film Lincoln. Secretary of State William Seward helped by twisting arms and promising patronage, especially in his home state of New York. Lincoln and Republican leaders succeeded in converting enough border state and Democratic congressmen to reach the two-thirds goal in the final vote on January 31—119 for, 56 against (a change of three votes would have reversed the outcome). The House erupted in jubilation; spectators wept and danced. In a speech the next day Lincoln stressed that slavery was the only thing that ever threatened to destroy the Union. He acknowledged the limitations of his Emancipation Proclamation, and praised the Thirteenth Amendment for freeing all slaves, everywhere, for all future time, “a King’s cure for all the evils” that had not been cured by the Proclamation.

But of course the measure could not become part of the Constitution until three fourths of the states, twenty-seven of the thirty-six states in the Union, had ratified it. Despite bitter Democratic opposition, by February 3 New York, Illinois, Rhode Island, Michigan, Maryland, and West Virginia had ratified the Amendment, and eleven more state legislatures followed by the end of the month. But then progress slowed considerably.

According to Oakes it is unclear, following Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, whether President Andrew Johnson ever formally required reconstructed Southern states to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment as a condition for readmission to the Union. But as Secretary of State Seward grew bolder, he told South Carolina’s provisional governor that the president “considers the acceptance of the amendment indispensable” to the state’s restoration. On November 14, the South Carolina legislature complied by ratifying the amendment, and in December Seward’s efforts led North Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, and even Florida to follow suit. It was not until December 18 that Seward officially certified that the requisite twenty-seven states had ratified the amendment—the same day that Delaware and Kentucky finally abolished the institution. This meant that during most of the year 1865, slavery was still legal in most of the Southern states and that more slaves may have been emancipated in December 1865 than in the four preceding years of war. But by year’s end, as Oakes makes clear, freedom was now truly “national.”

By underscoring the early Republican commitment to abolition as well as the success and importance of the First and Second Confiscation Acts, the first part of Oakes’s book implies a certain inevitability to the destruction of slavery in the Civil War. But despite his omission of some of the major barriers to emancipation, Oakes succeeds in conveying the complexity and fortuity of succeeding events, so the reader can well imagine a scenario in which slavery would have persisted for generations to come. Above all, Oakes brilliantly succeeds in distilling from a great mass of facts a series of clear themes and arguments that provide a new perspective on one of the central events in American history. (source:

New York Review of Books)