Neglect and rediscovery

From Mississippi History Now, "WPA Slave Narratives," by Neil R. McMillen, on February 2005 -- These narratives and other slave sources were not always highly valued. Although the WPA Slave Narratives were soon deposited in the Library of Congress, and soon thereafter also made available to researchers on microfilm, they were rarely used by scholars from any discipline. Historians often complained that good first-person slave sources were unavailable. Answering his own question – “What is it like to be a slave?” – one historian declared in 1939, “We do not know. The slaves themselves never told.”

More recently, new perspectives in a new age of civil rights have resulted in a new appreciation for the personal testimony of the slave. Published for the first time in 1972, the WPA Slave Narratives are now the basic building blocks for new understandings of slavery. Sometimes called “history from the bottom up” or “community and culture history,” the resulting “new history” of American bondage examines day-to-day life in the slave quarters from the point of view of the slaves themselves. Where once historians had often found the slaves to be contented, docile, and imitative of whites, the new histories generally emphasize slave resistance and slave initiative, slave cultural adaptation, slave social institutions, and slave religious autonomy.

Today, no historian would deny the wisdom of Frederick Douglass (1817-1895). Writing in his own book of slave remembrances, this famous run-away slave and abolitionist declared in 1855 that no free man could truly understand the life of the enslaved, because he “cannot see things in the same light with the slave, because he does not, and cannot look from the same point from which the slave does.”

Problems and limitations

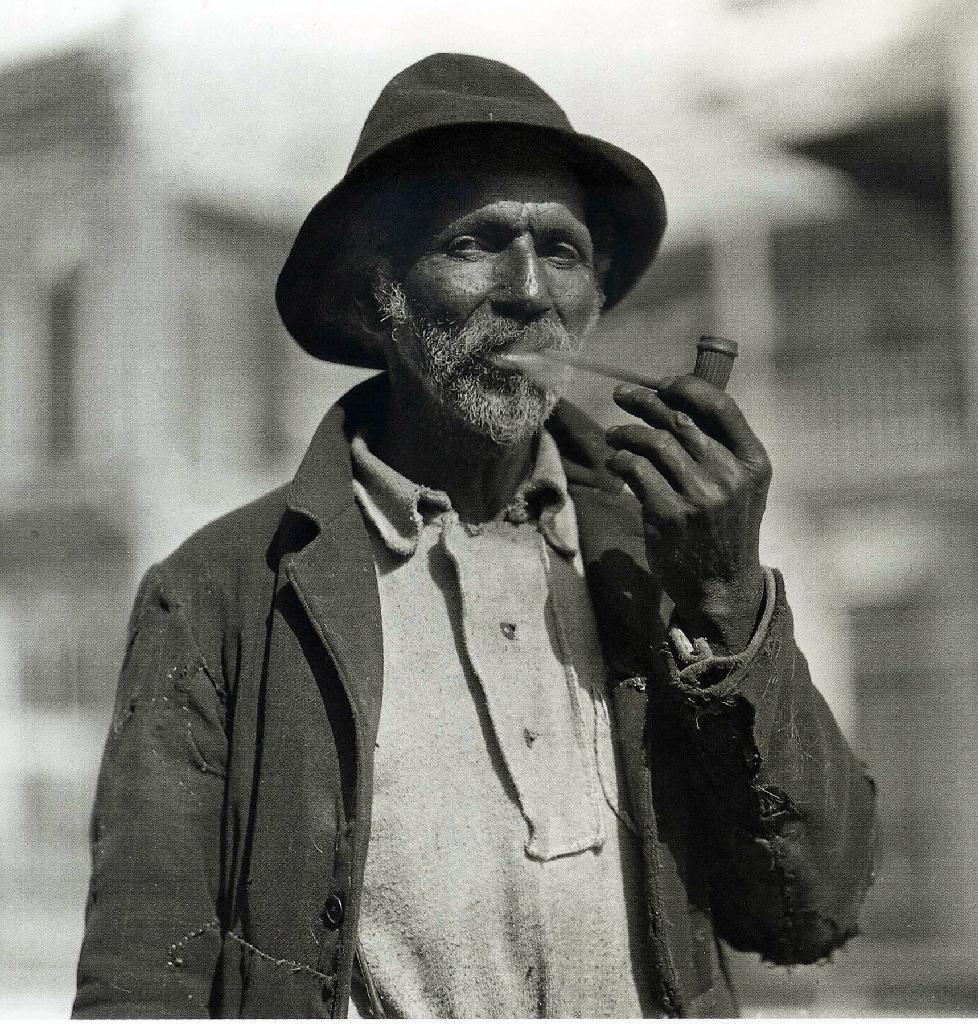

All significant slave occupations are represented in the WPA Slave Narratives, as are both large plantations and small farms. All of the respondents were elderly, of course. The average age was 85, and nearly one in every ten claimed to be 100 or more years old. All had been freed some seven decades before they were interviewed. Most had known slavery only in childhood or youth.

Unfortunately, the quality of the interviews rarely matched the quantity. Few of the WPA interviewers were adequately trained. With the rarest exceptions, the interviews were not tape recorded and the finished transcripts were not so much word-for-word representations of what ex-slaves actually said, but reconstructions based on the interviewers’ memory or field notes. Nearly all of the interviewers were white southerners and most of them were women. Far too often the tone and even the content of the interviews reflected the white supremacist values of the 1930s. The WPA workers often patronized or insulted the ex-slave interviewees, reconstructing their speech in the crudest “plantation style,” referring to them as “old darkies,” or as “auntie” and “uncle.” Too often interviewers accepted Old South mythology as truth, assuming that all slaves were contented, all masters kind, and all plantations idyllic.

For their part, the elderly former slaves may have spent most of their lives as free persons, but such freedom as they had known was anything but free. In freedom, not less than in bondage, they had been kept in their “place” by Jim Crow laws and customs designed to ensure white supremacy. Not surprisingly, during the interview process former slaves often seemed uncomfortable and cautious, eager to please their interviewers by supplying the “right answers” and by wearing the mask of racial submission.

When 90-year-old Liza McGhee was interviewed in Marshall County, Mississippi, a WPA worker found her “hesitant about talking freely as she feared the white people were planning to enslave her again.” McGhee did indeed chose her words carefully. “I remember some things about old slave days,” she said, “but I don’t want to say nothing that will get me in bondage again. I am too old now to be a slave. I couldn’t stand it.” That her concerns were widely shared was suggested by another former slave, Martin Johnson, who informed an interviewer in another state that, “Lots of old slaves closes the door before they tell the truth about their days of slavery. When the door is open, they tell how kind their masters was and how rosy it all was.” Lots did, but not all.

In fact, some of Mississippi’s former slaves spoke so bluntly about harsh conditions and cruel treatment that state FWP officials, apparently offended by such candor, chose to violate WPA guidelines and not forward their narratives to the Library of Congress in Washington. Thousands of pages of “bad” slave memories were discovered in the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in the 1970s.

Conflicting memories

All historical documents present problems for those who read them. All require close, careful reading and rigorous comparisons with other documents. In this respect, as experts now agree, the WPA Narratives are not different from other historical data. The records left by slaves and the records left by slave owners are both valuable. Both can mislead, but both can inform. Used carefully, each can contribute to the larger picture of slave life.

Those who read slave documents will immediately notice the great variety of opinions expressed. The ex-slaves, as it develops, were like everybody else – they did not speak with a single voice. Some were more than eager to assure WPA interviewers that they had been happy and well cared for as slaves. Others insisted that they hated slavery and that – hungry as they often were in freedom – they did not long for “dem olden times.” Some described good masters and mistresses; some described unspeakable cruelties. The most wary claimed either to have no memories worth recalling, or simply wouldn’t talk at all. “My conscience tells me to keep my mouth shet,” Rhoda Hunt (b.1854) told an interviewer,“let de dead rest and don’t bother trouble less trouble troubles you.”

The excerpts below from WPA Slave Narratives suggest the range of slave responses:

- “Slavery was one of the sins of the middle ages.” -- George Washington Miller (b. 1856) -- Clay County, Mississippi

- “I liked being a slave, our white folks . . . were good to us. . . . I had rather be a slave. . . . . I wish I wuz still in slavery.” -- Adam Smith (b. 1839) -- Tate County, Mississippi

- “When I was three or four years old my mother was whipped to death by the mistress with a cowhide whip.” -- Henry Walton (b.1852) -- Marshall County, Mississippi

- “I’s heard dat some white folks wuz mean to der niggers, but our Old Masta and Miss wasn’t.”-- Minerva Evans (b. 1840s) -- Harrison County, Mississippi

- “Give me freedom, or give me death.” -- Belle Caruthers (b. 1847) -- Marshall County, Mississippi

- “[Sharecropping] wuzn’t much diffent from slavery. We lived in quarters, used de white folks horses en ploughs en helped raise our own food. We just change a marster for a boss.” -- James Lucas (b. 1833) -- Adams County, Mississippi

- “When you is a slave, you ain’t got no mo’ chance than a bullfrog.” -- Virginia Harris (b. ?) -- Coahoma County, Mississippi

- “I seed slavery from all sides. I’se seed ’em git sick and die an’ buried. I’se seed ’em sole [sold] away from der loved ones. I’se seed ’em whipped by de overseers, an’ brung in by de patrol riders. I’se seed ’em cared fo’ well wid plenty ter eat an’ clo’se ter keep ’em warm, an’ wid good cabins ter live in.” -- Rosa Mangum (b. 1831) --- Simpson County, Mississippi

- “My white folks was good to me. I had a heep better time when I growed up than folks does now. . . . Shucks I was a heep better off.” -- Rube Montgomery (b. 1861?) -- Choctaw County, Mississippi

- “My mammy . . . belong to old man Weathersby in Amite County. He was de meanes’ man what ever lived. My pappy was sol’ befo’ I was born. I doan know nothin’ ’bout him. . . . Mammy said when I was jes big ’nough to nuss an’ wash leetle chulluns, I was sol’ to Marse Hiram Cassedy an’ dat man give me ter his darter, Miss Mary, to be her maid. . . . I was never whupped afte’ I went to Marse Cassedy.” --- Fanny Smith Hodges (b. ?) --- Pike County, Mississippi

- “Slavery Days wuz bitter, bitter, an’ I shall never fo’git the sufferin. . . . My Marster was mean an’ cruel an’ I hates him, Hates him. . . . I knows it ain’t right to hev’ hate in de’ heart, but God Almight, it’s hard to be forgivin’.” --- Charlie Moses (b. 1860?) --- Lincoln County, Mississippi.

What then should a 21st century reader make of testimony so diverse? Clearly, the narratives seem to point in many directions, offering support for a diversity of conclusions. A shrewd reader will approach these old records with an open mind, with a good foundation in United States history, and with a recognition that human experience varies widely. That reader should also know that human memory is imperfect, that even people with “good memories” tend to view the past in the light of the present. (source: http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us/articles/64)

No comments:

Post a Comment