From the New York Times Disunion, "Icons of Cruelty," by Joan Paulson Gage, on 5 August 2013 -- Two iconic photographs of former slaves documenting the torture inflicted on them by their owners were widely circulated during the Civil War as anti-slavery propaganda, and both appear in the current exhibit “Photography and the American Civil War” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Although the images were extensively reproduced and helped to turn public opinion against slavery, the stories of the two men in these shocking photographs are little known today.

Perhaps the most famous anti-slavery image ever made is “The Scourged Back,” in which an escaped slave named Gordon poses to reveal the web of raised scars covering his body. An engraving of this photograph, attributed to McPherson and Oliver of New Orleans, was published on July 4, 1863, in Harper’s Weekly, along with the explanation that Gordon had escaped his master in Mississippi and threw the pursuing bloodhounds off his scent by rubbing himself with onions. After an arduous journey, he managed to reach the Union Army stationed at Baton Rouge, La., 80 miles away.

International Center of Photography: “Gordon, a Runaway Mississippi Slave, or ‘The Scourged Back,’” 1863, attributed to McPherson and Oliver.

Gordon decided to enlist in the Union Army — something that President Lincoln had legalized only months earlier — and during the required medical examination, the officers saw his back “furrowed and scarred with the traces of a whipping administered on Christmas Day last.” They called for a photographer to document it. On April 16, 1863, S. K. Towle, surgeon, 30th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers, sent a C.D.V. (carte de visite) photograph of Gordon’s back with a letter to W. J. Dale, surgeon general of the state of Massachusetts. He wrote: “Few sensation writers ever depicted worse punishment than this man must have received, though nothing in his appearance indicates any unusual viciousness — but on the contrary he seems INTELLIGENT AND WELL BEHAVED.”

The Harper’s article also included an engraving of “Gordon in his uniform as a U.S. Soldier,” holding his musket. Little is known of Gordon’s military career. One published report said that he served as a sergeant in a black regiment that fought bravely at the siege of Port Hudson on May 27, 1863 — the first time that African-American soldiers played a leading role in an assault.

Meanwhile, the photograph of Gordon’s scars took on a life of its own as a weapon of the abolitionists. It was reproduced and sold in the carte-de-visite form by C. Seaver of Boston; by McAllister of Philadelphia, who first titled it “The Scourged Back”; and by other American photographers, including Mathew Brady. Another version was issued by a British publisher, titled “The ‘Peculiar Institution’ Illustrated”; an ironic reference to the euphemism for slavery used by Southerners.

On the back of the British version were printed remarks from newspapers, including this from The New York Independent: “This Card Photograph should be multiplied by the 100,000, and scattered over the States. It tells the story in a way that even Mrs. [Harriet Beecher] Stowe [author of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’] cannot approach, because it tells the story to the eye.”

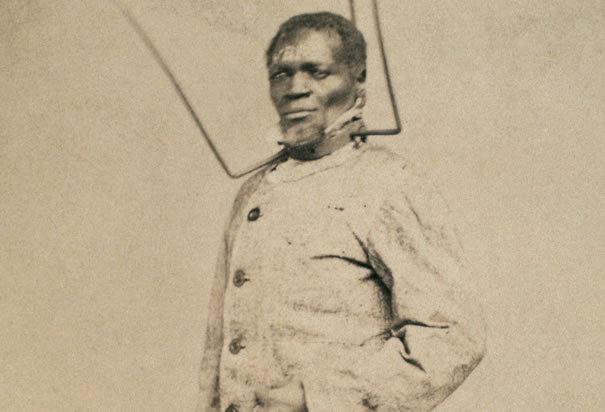

While the photograph of Gordon’s back may first have been made as a clinical document and then turned into propaganda, the C.D.V. photograph of Wilson Chinn with chains and torture instruments was from the start meant to excite anti-slavery emotion.

In December of 1863, eight former slaves were brought north from New Orleans, sponsored by the American Missionary Association and the National Freedman’s Relief Association. They were taken to photographers’ studios in New York and Philadelphia and posed in dramatic scenes for photographs, which were sold for 25 cents each to raise money for the education of former slaves in Louisiana. The other purpose of these photographs was to increase abolitionist sentiment in the North by using the fledgling science of photography to dramatize the evils of slavery.

Five members of the group were children aged from 6 to 11 — three girls and two boys — and four of them were so fair-skinned that they appeared entirely Caucasian, although all five had been born as slaves. The only adult in the series of photos, which were made by Myron H. Kimball and Charles Paxson of New York and J. E. McClees of Philadelphia, was Wilson Chinn, identified on most of the photographs as “a branded slave.”

Private Collection, Courtesy William L. Schaeffer: “Wilson. Branded Slave from New Orleans,” 1863, taken by Charles Praxson.

On Jan. 30, 1864, Harper’s Weekly published a large engraving of the group portrait. In an article titled “Emancipated Slaves White and Colored,” Harper’s introduced each individual. Here’s the paragraph about Chinn:

“Wilson Chinn is about 60 years old. He was ‘raised’ by Isaac Howard of Woodford Country, Kentucky. When 21 years old he was taken down the river and sold to Volsey B. Marmillion, a sugar planter about 45 miles above New Orleans. This man was accustomed to brand his negroes, and Wilson has on his forehead the letters ‘V.B.M.’ Of the 210 slaves on this plantation 105 left at one time and came into the Union camp. Thirty of them had been branded like cattle with a hot iron, four of them on the forehead, and the others on the breast or arm.”

(The letters branded on Wilson’s forehead were not clear in the photograph, and the photographer, Kimball, had to retouch the negative to make them visible.)

The Northern photographers posed the children in fine clothes and sentimental poses with titles like “Oh! How I Love the Old Flag” and “Our Protection.” Wilson Chinn was posed in one scene, “Learning Is Wealth,” apparently reading a book to three of the fair-skinned children. But his other photos were meant to illustrate the savagery of the treatment of slaves. He was posed by Paxson in profile in the C.D.V. from the Met’s exhibit wearing a spiked collar and leg irons and holding a nail-studded paddle. (There exist at least two other versions — a frontal view by Kimball with the paddle on the floor and a third, also by Kimball, in which the instruments of torture are all on the floor. Wilson stands with his left foot atop the paddle — no doubt symbolizing that he is now free.)

The grisly images of Wilson wearing the spiked collar are the rarest and most valuable. In 2002 one of the Kimball C.D.V.’s sold on eBay for $1,846.

Jeff L. Rosenheim, the Met’s curator of photographs, wrote in the catalog for “Photography and the American Civil War” that he found the Wilson Chinn photo especially puzzling: “Paxson No. 8, Wilson Branded Slave from New Orleans … is a bewildering instance of Civil War photographic marketing that asks as many questions about the individuals who commissioned the portraits as it does about those who would purchase or collect these images.”

Undoubtedly Wilson Chinn, and even the children who traveled with him from New Orleans, knew that their role in coming North was to dramatize the evils of the “peculiar institution” from which they had recently escaped.

The images of Wilson Chinn in chains, like the one of Gordon and his scarred back, are as disturbing today as they were in 1863. They serve as two of the earliest and most dramatic examples of how the newborn medium of photography could change the course of history. (source: New York Times Disunion)

No comments:

Post a Comment