Books of The New York Times, "What Emancipation Didn’t Stop After All," by Janet Maslin, on 10 April 2008 -- In “Slavery by Another Name” Douglas A. Blackmon eviscerates one of our schoolchildren’s most basic assumptions: that slavery in America ended with the Civil War. Mr. Blackmon unearths shocking evidence that the practice persisted well into the 20th century. And he is not simply referring to the virtual bondage of black sharecroppers unable to extricate themselves economically from farming.

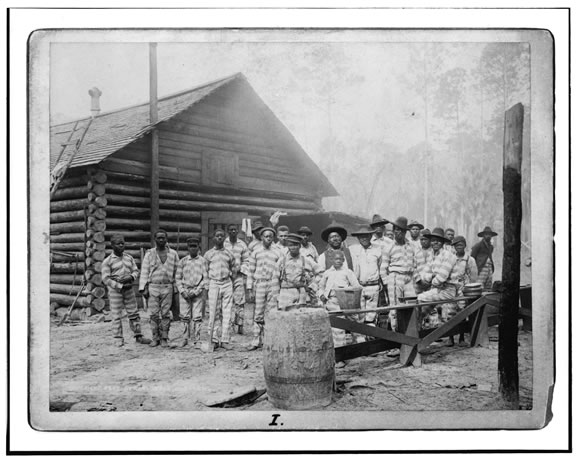

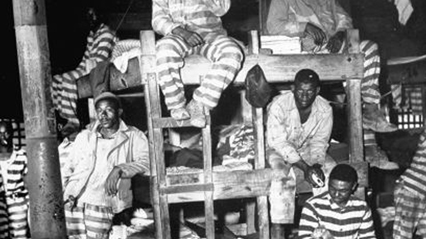

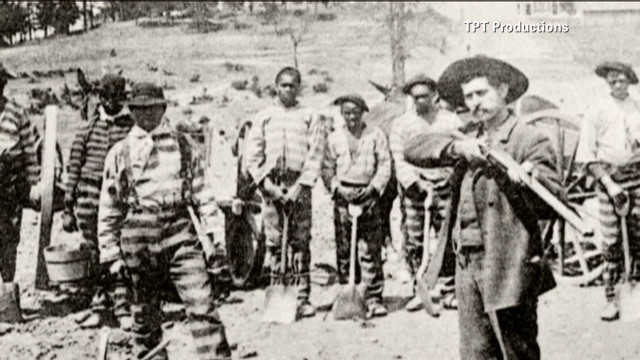

He describes free men and women forced into industrial servitude, bound by chains, faced with subhuman living conditions and subject to physical torture. That plight was horrific. But until 1951, it was not outside the law.

All it took was anything remotely resembling a crime. Bastardy, gambling, changing employers without permission, false pretense, “selling cotton after sunset”: these were all grounds for arrest in rural Alabama by 1890. And as Mr. Blackmon explains in describing incident after incident, an arrest could mean a steep fine. If the accused could not pay this debt, he or she might be imprisoned.

Alabama was among the Southern states that profitably leased convicts to private businesses. As the book illustrates, arrest rates and the labor needs of local businesses could conveniently be made to dovetail.

For the coal, lumber, turpentine, brick, steel and other interests described here, a steady stream of workers amounted to a cheap source of fuel. And the welfare of such workers was not the companies’ concern. So in the case of John Clarke, convicted of “gaming” on April 11, 1903, a 10-day stint in the Sloss-Sheffield mine in Coalburg, Ala., could erase his fine. But it would take an additional 104 days for him to pay fees to the sheriff, county clerk and witnesses who appeared at his trial.

In any case, Mr. Clarke survived for only one month and three days in this captivity. The cause of his death was said to be falling rock. At least another 2,500 men were incarcerated in Alabama labor camps at that time.

This is a very tough story to tell, and not just because of its extremely graphic details. Mr. Blackmon, who was reared in the Mississippi Delta and is now the Atlanta bureau chief of The Wall Street Journal, must set forth a huge chunk of history. He writes of how the emancipation of slaves left Southern plantations “not just financially but intellectually bereft” because the slaves’ knowledge and experience could be indispensable; how the rise of industry reshaped the South; how a new generation of African-Americans who had not known slavery found themselves threatened by it; how slavery intersected with efforts to unionize labor; and even how, once blacks lost their voting rights but still had clout at the Republican convention, they were strategically important to President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1904 election campaign.

The roles of elected officials in acknowledging and stopping this new slavery are a crucial part of Mr. Blackmon’s story. Needless to say, it is complicated. The book describes the 1903 investigation authorized by the Justice Department, the trial of accused slave traders and the aggressive stance taken by Warren S. Reese Jr., the United States attorney in Alabama, in prosecuting his case.

“As allegations of slavery in his jurisdiction multiplied, Reese demonstrated a prehensile comprehension of the murky legal framework governing black labor,” Mr. Blackmon writes, “and a hard-nosed unwillingness to ignore the implications of the extraordinary evidence that soon poured into his office.”

The resulting trial is among this book’s many zealously researched episodes. (Mr. Blackmon’s sources range from corporate records to one “Sheriff’s Feeding Account, 1899-1907.”) Its outcome was promising, but there were loopholes. As one sign of this story’s complexity, consider that the traders were tried on charges of peonage.

Those charges turned out not to be applicable in Alabama. And in another such case, lawyers would argue that the charge should instead be involuntary servitude. Reformers were dealing with “a constitutional limbo in which slavery as a legal concept was prohibited by the Constitution, but no statute made an act of enslavement explicitly illegal.”

Mr. Blackmon’s way of organizing this material is to bookend his legal and historical chronicle with the personal story of Green Cottenham, a black man born free in the mid-1880s. This gets “Slavery by Another Name” off to a shaky start, if only because many of Mr. Blackmon’s wordings are speculative. The book underscores that if black Americans’ enslavement to U.S. Steel (which, when it acquired the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company, became a prime offender) is analogous to the slavery that occurred in Nazi Germany, it also emphasizes that the American slaves’ illiteracy meant there would be no written records of their experience. So imagining Mr. Green’s experience becomes something of a stretch.

But as soon as it gets to more verifiable material, “Slavery by Another Name” becomes relentless and fascinating. It exposes what has been a mostly unexplored aspect of American history (though there have been dissertations and a few books from academic presses). It creates a broad racial, economic, cultural and political backdrop for events that have haunted Mr. Blackmon and will now haunt us all. And it need not exaggerate the hellish details of intense racial strife.

The torment that Mr. Blackmon catalogs is, if anything, understated here. But it loudly and stunningly speaks for itself. [source: The New York Times ]

Quantum Binary Signals

ReplyDeleteProfessional trading signals sent to your cell phone every day.

Follow our trades today & gain up to 270% a day.