The Washington Post, "A Sorry History," by Laura Wexler, on 19 June 2005 -- "Dear Pres. Truman," the letter begins, "I am a little girl about 12 year old and I think that someone up there in Wash DC ought to put a stop to these murder . . . because it is getting terrible to walk down the street any moore."

Scrawled in childish handwriting that runs crookedly across the page, the letter is signed by Miss Vinita Ann, one of the thousands of citizens who wrote to President Harry Truman and Attorney General Tom Clark in the wake of the lynching of two black men and two black women in Walton County, Ga., on July 25, 1946. Though the letters varied in their specifics, each made the same general demand: The federal government should use its power to punish those who committed the lynching, and act to prevent future lynchings.

Last Monday, the Senate offered Vinita Ann -- now about 71 years old, if she is still alive -- a kind of reply when it formally apologized to the nation's nearly 5,000 lynching victims and their descendants for having failed to enact anti-lynching legislation.

Like Mississippi's current efforts to pursue justice in both the 1955 killing of 14-year-old Emmett Till and the 1964 murders of civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, the Senate's apology speaks of progress and redemption -- a new day in race relations. And yet, the apology is ultimately unsatisfying. Though it would be comforting to finger the Senate as the "bad guy" -- the evildoer who, five decades later, has seen the light and is asking for forgiveness -- the reality is that the Senate is not the main villain in the story of American lynching. And so its apology is mismatched to the crime. Admirable and welcome as it is, it is not the balm that can heal the wound.

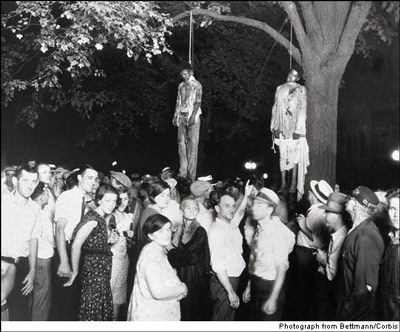

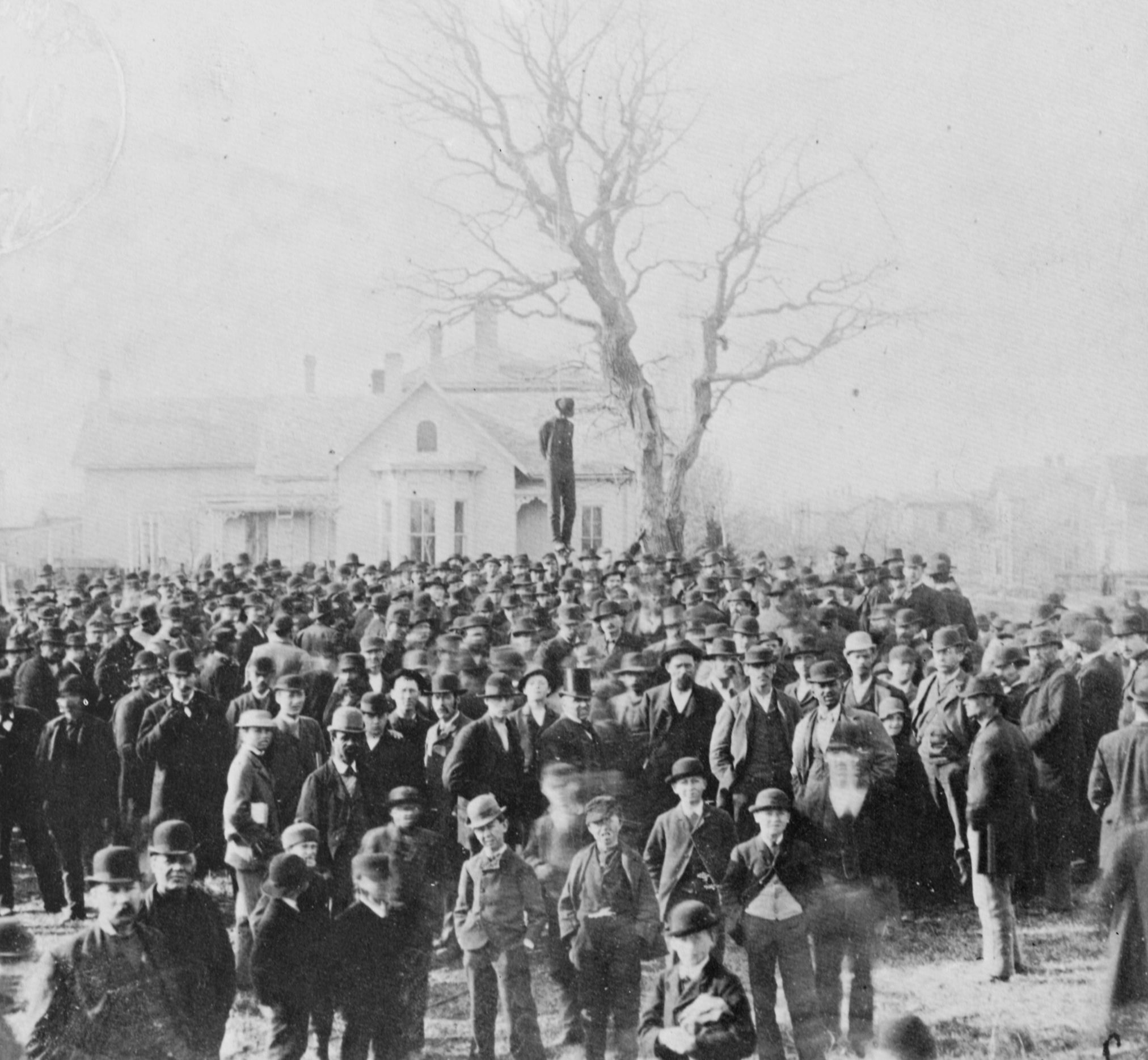

Lynching -- unlike simple murder -- is a form of collective violence in which individuals act with the explicit or implicit support of the community, or at least without its condemnation. A particularly American brand of domestic terrorism, it thrived and went unpunished from the late-19th through the mid-20th century largely because of the racism of American citizens.

The fact is, even if the Senate had passed one of the 200 anti-lynching bills proposed since 1909, lynchers still would have gone unpunished, and lynchings still would have continued to occur. We know this to be true because, starting in 1939, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Civil Rights Section (CRS) of the Justice Department, the federal government did pursue lynchers -- but repeatedly failed to earn convictions.

In 1942, a mob in Sikeston, Mo., broke into a state jail, seized a black prisoner named Cleo Wright, tied his feet to the back of a car, dragged him through the streets and finally burned him to death. After a state grand jury failed to indict anyone for murder, the CRS asked a federal grand jury to indict under Sections 51 and 52 of the United States Code, the two civil rights statutes that remained from those passed in the wake of the Civil War. But the federal grand jury followed the lead of its state counterparts and also failed.

One year later, CRS lawyers persuaded a federal grand jury to return indictments against five men in the lynching of Howard Wash in Laurel, Miss. But after the defendants' attorney raised the issue of states' rights at trial, the jury found all five not guilty -- even though one had signed a confession admitting to having participated in the lynching.

Certainly these failures, just two among many, resulted partly from the federal government's slim jurisdiction in lynching cases; it could prosecute only for civil rights violations -- not for murder, which is a state crime. But even if the Senate had solved the jurisdictional problem by passing a federal anti-lynching law, that law would still have had to be enforced by American juries. And throughout the first half of the 20th century, it was the rare court that would convict, or even indict, a white man for a serious crime against a black man -- especially in the South, where the majority of lynchings occurred.

Not until October 1946, seven years after its creation, did the CRS win its first victory in a lynching case, when Tom Crews, a Florida constable, was convicted of civil rights violations in the killing of a black farmhand. That Crews's punishment -- a $1,000 fine and one year in prison -- was so paltry was, ironically, one of the reasons the jury probably voted to convict him. Had the punishment been life in prison -- had, in other words, the punishment been for the crime of murder and not for the crime of civil rights violations -- it is hard to believe the Florida jury would have acted the same. Even the federal government's few successes in prosecuting lynchings, then, can be seen as proof of the fact that in the past jury problems -- which is to say, the racism of the ordinary American citizen -- even more than the jurisdictional problems, account for the fact that less than 1 percent of lynchers were ever convicted.

This is not to argue that the Senate shouldn't have passed a federal anti-lynching law. It should have. This is not to argue that the federal government should not have pursued lynchers; it certainly should have. The mere presence of federal agents in a county that had experienced a lynching sent a message to locals from the Justice Department: We may not be able to convict you, but we will make your life hell for a few months. That message, in conjunction with widespread media coverage of lynchings, growing African American political and economic power and the increasing urbanization of the South, among other things, led to the eventual end of the lynching epidemic. After the quadruple murders on July 25, 1946, the nation would never again see as many victims lynched on a single day. In 1952, the nation finally celebrated its first lynchless year, And by 1968, there were few enough incidents that the Tuskegee Institute, which had documented lynchings since 1882, stopped counting.

Somewhere in the early 1990s -- perhaps in 1994, when Byron de la Beckwith was convicted for the murder of civil rights leader Medgar Evers 30 years after the murder itself, -- we entered an age of atonement in which we still live, and likely will for a while. In the best cases, revisiting the sins of our racial past has produced justice. In other cases, it has provided the consolation prizes of official acknowledgment and apology, which, depending on where you stand -- and how much you have suffered -- may be consoling, or may not.

It is admirable that the Senate has honestly and publicly acknowledged its role in American lynching. But just as no one can ask forgiveness for a sin he or she did not commit, the Senate cannot apologize for the real crime of lynching: the countless burnings, beheadings, mutilations, assassinations and hangings that occurred on American soil. And it cannot apologize for the failure of countless juries to convict those who committed such hideous acts.

A crime as widespread and inhumane as lynching -- or slavery or genocide -- requires multiple apologies, because multiple individuals and entities created, carried out and benefited from it. In this case, the Senate, a bit player in the tragedy, has offered its apology. But instead of providing comfort, it has pointed to the gaping hole that exists, and will always exist, where the other apologies -- the ones from citizens-- should have been. [source: The Washington Post; Laura Wexler, who lives in Baltimore, is the author of "Fire in a Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America" (Scribner). © 2005 The Washington Post Company]

kevin durant shoes

ReplyDeletelouboutin shoes

calvin klein outlet

lebron 17

goyard

jordans

kyrie spongebob

yeezy shoes

supreme hoodie

off white clothing

replica bags in dubai replica gucci h8h36v4m71 replica bags in london zeal replica bags reviews replica hermes handbags u7i52z3l54 replica evening bags view it m8r22i9c42 bags replica gucci replica bags from turkey

ReplyDelete