As reported in the Cape May Gazette, "Bizarre History of Cape May > Slavery in Cape May County lasted 146 years," by Jacob Schaad Jr., on 5 June 2023 -- The first reported slaves were brought to the area now known as Cape May and Lower Township in 1688. The last slave was said to have been freed in 1834.

During those 146 years, the territory to become Cape May County was to tell its own story of slavery, some of it more moderate than the South, but all of it negative in its final summary.

The man who started it never lived here, and never even set foot on the soil, but still was a powerful influence in the early development of the cape.

Dr. Daniel Coxe was an English court physician who wanted to establish a “New Empire in America.” From his distant shore he hired an agent who bought 95,000 acres of Cape May peninsula land for him, some from the Lenape people who were paid, among other items, 16 gallons of rum, a hot item in those days of merchandising.

“I pity them greatly,” said one semi-sympathizer of the slaves, “but I must be mum. For how could we do without sugar and rum?”

Coxe’s idea for a “New Empire in America” apparently included slaves or, as he put it in 1688, “four stout Negroes.” Two of them were married in Cape May County and their contract stipulated that if they had any children they must serve until they reached the age of 31 or whenever the law said.

By the middle of the 18th century slavery was on the rise in Cape May County. More than 50 slaves, most of them African-Americans and a few Native Americans, were said to be on the plantations of the county’s property owners. Jacob Spicer Jr., who owned vast real estate here, mentioned a “Red Negroe” in his will, and Abigail Hand, whose surname was to live long in Cape May history, suggested that her family included “Indian and black folk.”

The slaves were bought in Philadelphia where people bought furniture, clothing and books.

“I set out from home to go to Philadelphia to buy a Negro or two,” said Aaron Leaming Jr., a prominent member of the original whaling families who came to this area from Connecticut and Long Island in hopes of finding prosperity.

In the mid-1700s the whalers owned 91 percent of the slaves on the cape, and they willed their slaves to other members of their families. In some cases, what amounted to human chattels were treated kindlier than those in the deeper southland. They were allowed to live with the families and sometimes sleep in the master’s kitchen near the fireplace.

It was not always the safest place to be, however. In one case, it was reported, a heavy wind blew down the chimney and killed the sleeping son of a slave.

There were some slave owners, like Aaron Leaming Jr., who gave their slaves more freedom than the traditional masters. He allowed them to travel around the county on their own, to go fishing and to visit others. He was also said to take care of the ill as if they were members of his own family.

Nevertheless, they were still slaves, inventoried much like horses and cows and other animals, and it was to get worse after the Revolutionary War when Cape May County was to experience the biggest growth in slave owning in its history.

Official tax records show that in the Lower Precinct, which encompassed Cape May and Lower Township, the slave population increased from six to 33 between 1774 and 1784. In the Middle Precinct the numbers jumped from 18 to 63 during the same period. Some whaler families who owned no slaves before the war were affluent enough to buy some for their properties, which were called plantations.

As prevalent as slavery was, there was some movement to curtail or abolish slavery. The Quakers had taken action to forbid the immigration of slaves into other areas of New Jersey, but were not successful in Cape May County where the whalers were still bringing them. There is some historical conjecture that some of the owners did not formally declare all their slaves so they would not have to pay taxes on them.

There was actually a court case in 1768 in which a slave was freed. His name was Jethro and his mother was Charity Briggs, a mulatto who was free. Jethro was bound over to a series of masters but eventually was declared a free man on a motion by the attorney general.

By the time the 19th century arrived, the county was beginning to take a different look at slavery. In 1802 the manumission of slaves began here when slave owner John Stites freed Nancy Coachman in Lower Township. The New Jersey legislature had paved the way in 1786 when it banned the further importation of slaves into the state.

It took another 18 years before the legislature allowed children born of slaves after 1804 to be declared free when women turned 21 and men turned 25.

Slavery was tardily and formally abolished in New Jersey in 1846, although most slave owners in Cape May County had freed their human chattels before that. Some of the freed slaves and perhaps a few runaways settled in remote areas of the county, which still had to be developed. One of the first African-American communities to be developed was in the section of Lower Township that is now known as Erma.

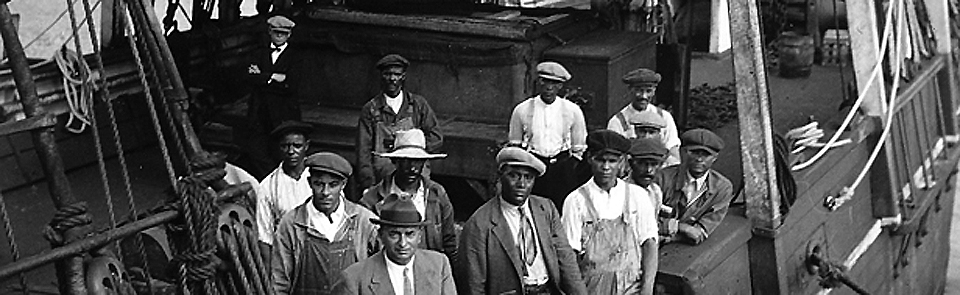

Most of the freed went to work as farm laborers or domestics, some at the hotels that were springing up the still-named Cape Island. More progress was yet to come. In 1850, more than a decade before the Civil War that was to change it all, three African-American families paid taxes on properties they owned. Another turned farmer. Some of the slaves opted to stay with their former masters in their new lives as a free people.

It was an era too when the name of Harriet Tubman was to gain prominence in the local history of slavery. She was an escaped slave from Maryland, worked at the Congress Hall and was active in the Underground Railroad which helped more than 300 slaves to their freedom.

So it was that before a war that tore the nation apart, the people of the southernmost territory in New Jersey were part of the issue that ignited the Civil War. Slavery was here too, not as volatile as that in the South, but that doesn’t make it less excusable. [source: The Cape May Gazette. (Some of the information in this article was researched in the books, “Cape May County, New Jersey, The Making Of A American Resort Community,” by Jeffery M. Dorwart and “Cape May County, New Jersey, 1638-1897,” by Lewis Townsend Stevens.)]

All the paperwork, the financing, the serious amounts of energy in looking

ReplyDeleteand negotiating offers will take a toll on the most experienced home buyer Payday Loans No don't look for perfect performance, however, you should note if you will find a good deal of bad reviews, this can be a business to express faraway from.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this. I am an African American woman who grew up in Cape May—Erma, to be exact. This connects all kinds of dots. I would still be interested to learn what happened in Erma that turned into an all white area.

ReplyDelete