From the Wall Street Journal, "Slave Narratives From Unlikely Sources: Two white writers grapple with the task of writing about slaves. Sam Sacks reviews Margaret Wrinkle's Wash" and Tara Conklin's The House Girl,'" on 15 February 2013 -- Addressing an assembly of the NAACP in 1926, W.E.B. Du Bois posed a hypothetical scenario that, for all our hopeful talk of a post-racial age, still has a nagging relevance. "Suppose," he said, "the only Negro who survived some centuries hence was the Negro painted by white Americans in the novels and essays they have written. What would people in a hundred years say of black Americans?"

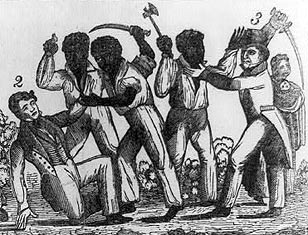

We can rightfully console ourselves that the telling of history is no longer nearly so one-sided. But for white writers trying to reckon with the past, Du Bois's warning that inequalities can be propagated through art remains a cause for anxiety, as well as controversy. In 1967, mere months after William Styron published "The Confessions of Nat Turner," a novel about the leader of an 1831 slave rebellion, critics responded with a fiercely denunciatory collection of essays accusing Styron of "revisionist emasculation"—of having projected a white Southerner's biases onto an iconic black figure. (Not everyone agreed: James Baldwin called the book "the beginning of our shared history.") The polarized reactions last year to Quentin Tarantino's slave-revenge fantasy film, "Django Unchained," revealed the same deep-set nervousness on the part of black and white audiences alike.

Behind these fears is the uneasy knowledge of the unregulated power that storytellers wield in shaping our conceptions of truth. The voices of the past can't speak for themselves and must rely on the artists of the future to honor them. It's a profound responsibility and one that Margaret Wrinkle meets in her brilliant novel "Wash" (Atlantic Monthly Press, 408 pages, $25). She shows not only the courage to submerge herself in the Stygian world of plantation slavery but also the grace and sensitivity to bring that world to life.

"Wash" is set mostly in the early 1820s on a farm outside Nashville run by James Richardson, a veteran of both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. He has fallen into debt and embarked on a moneymaking venture: putting his slave Wash (short for Washington) out to stud, in transactions he describes in the phlegmatic terms of a horse breeder: "Send Wash over to my friend Miller's on a Friday, put him with three or four per day. Even if only some take, that will mean ten new negroes, worth two hundred apiece once weaned."

Ms. Winkle then enlarges on this premise, spinning out the story of Wash's upbringing and of the lives of the people closest to him. Narrative roles are given to Wash, fellow slaves and his succession of masters, creating a dense, hypnotic ensemble of voices similar to the effect achieved in Peter Matthiessen's momentous retelling of the life of a Florida sugar plantation owner, "Shadow Country" (2008).

Author Margaret Wrinkle

We read of Wash's mother, Mena, a "saltwater" slave stolen from Africa who initiates her son into the secret traditions that both whites and "countryborn" slaves fearfully refer to as "conjure"—the making of stone altars and talismanic pouches holding hair and roots that connect Wash to a spirit world inaccessible to whites. Wash bonds with the midwife and herbalist Pallas ("Even when she gets gone, I still have the thought of her, spreading quiet on my mind"), partly because she carries her own sexual scars—as a teenager, she was rented to a neighboring farm so that the white hands could rape her and thus avoid the unpleasant consequences of impregnating their own slaves.

If it sounds like the stuff of gothic horror, the striking thing about "Wash" is the chilling orderliness that motivates these monstrosities. According to the logic of economics and the law, sending out Pallas for rape and Wash for breeding makes practical business sense. Richardson's narration reveals him to be intelligent and thoughtful—he doesn't even seem to be racist, in that he doesn't comfort himself with the delusion that blacks are in any way inferior. But he is too afraid of financial ruination to oppose the system presented to him. As Pallas says of one of the whites who treated her kindly before forcing himself on her: "He was a good man but not good enough."

Ms. Wrinkle juxtaposes the merciless dispassion of slaveholding with bracing plunges into the emotions of her characters. Foremost of which is Wash, whose life is a long, punishing journey toward finding the inner solace that will allow him to discover joys even from his sexual degradation. He fills his mind with pictures of "Pallas's slender shoulders disappearing down the path ahead of him into the heart of the swamp. The pale bone colored turtle shell she found for him to hide in the leaves covering Mena's grave. All these children, growing up looking like him whether they like it or not." It's from patriarchs like Wash as well as like Richardson, Ms. Wrinkle shows, that the U.S. was born.

Author Tara Conklin

Tara Conklin's debut, "House Girl" (William Morrow, 372 pages, $25.99), begins on a Virginia tobacco farm in 1852. Josephine Bell, the attendant to the house's ailing mistress, has decided to run away. Just as Wash understood that even his sexual life was his master's property, Josephine is provoked by the awareness that "she possessed nothing, that she moved through the world empty-handed with nothing properly to give, nothing she might lay claim to."

But before Josephine can attempt her escape, Ms. Conklin moves us to 2004 Manhattan, where Lina Sparrow, a young white attorney, has been assigned to a lawsuit for slavery reparations. Lina's research leads her to Josephine, who may have been responsible for some acclaimed paintings attributed to her mistress and who may have living descendants entitled to a payout.

At first Ms. Conklin presents the two women's stories in parallel, but as the novel progresses the author loses her nerve and gravitates more and more toward the safer, duller events of Lina's life. Soon Josephine and her experiences in the Underground Railroad appear only in the obscured form of archival documents that Lina has unearthed—an unfortunate irony, since the ostensible point of the novel is that voices silenced by slavery deserve to be heard. In the end, "House Girl" is a risk-averse derivative of Kathryn Stockett's mega-bestseller, "The Help." Yet in a very different way from "Wash" it drives home an important truth: The past is a dangerous place to visit, and not for the faint of heart. [A version of this article appeared February 16, 2013, on page C6 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Slave Narratives From Unlikely Sources. (source: Wall Street Journal)]

No comments:

Post a Comment