As reported in the Lexington Herald-Leader, by Greg Kocher, "Kentucky supported Lincoln's efforts to abolish slavery — 111 years late," on 23 February 2013 -- Here's an OMG fact for you: The Kentucky legislature didn't go on record against slavery until 1976 — 111 years after the 13th Amendment prohibiting involuntary servitude became the law of the land.

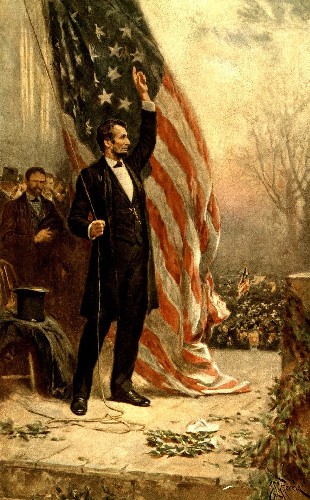

Lincoln, with 12 nominations at Sunday's Academy Awards ceremony, tells of the president's struggle to have Congress pass the amendment.

What isn't told is that Kentucky, Lincoln's birthplace, refused to ratify the amendment. Mississippi was another; more on that later.

The movie depicts only the first step of the process to add an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Moviegoers see passage of the amendment in the House of Representatives in 1865. But the amendment's story didn't end there.

Before an amendment can be added to the U.S. Constitution, three-fourths of the states must pass or ratify it. That process wasn't finished and verified until December 1865, eight months after Lincoln's assassination.

To understand why Kentucky rejected ratification, some context is necessary.

Slavery had existed in Kentucky since before it achieved statehood in 1792. In 1790, slaves were a little more than 6 percent of the population. By 1830, they were 24 percent of the population. By 1860, the year before the start of the Civil War, Kentucky had 225,000 slaves; most lived in the Bluegrass region and in the corridor between Lexington and Louisville.

Kentucky's first constitution, written in 1792, protected the right to own slaves. Slave labor was used to grow hemp in the 1800s, and tobacco in the central and western regions of the state. By 1850, 28 percent of white families owned slaves, but the average slaveholder owned five slaves or fewer.

At the start of the Civil War, Lincoln had hoped to encourage border states like Kentucky to take the initiative in abolishing slavery themselves, according to historians Lowell Harrison and James Klotter. Lincoln tried several times to get Kentucky to adopt a plan of compensated emancipation. It would work like this: If a state committed itself to a definite date to end slavery, then Lincoln would recommend to Congress that owners receive $400 for each slave. The plan didn't fly.

When Lincoln decided that ending slavery would help win the war, he declared slaves free only in those areas controlled by the Confederacy. His Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 did not affect Kentucky. Even so, the proclamation attracted protest in the Bluegrass.

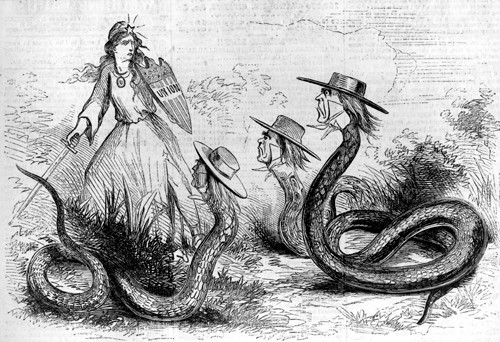

"Most Kentuckians supported the Union with the understanding that a state had the right to deal with slavery as a matter of state's rights," wrote James Ramage, a professor of history at Northern Kentucky University, in an email. "When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, most Kentucky Unionists felt betrayed and declared that they would never accept freeing the slaves."

Kentucky Gov. James F. Robinson denounced the Emancipation Proclamation in his message to the legislature in early January 1863. The legislature also denounced the proclamation "as unwise, unconstitutional and void," and there was talk in the state of recalling Kentucky troops from the Union army. Some even advocated that Kentucky secede from the Union.

Such talk embarrassed those who supported emancipation. Samuel Lusk wrote to a friend on Feb. 4, 1863: "If the president is resolved on going to hell and destroying the best government on earth, let him place himself under the control of Kentucky politicians and he will soon have accomplished his purpose."

Meanwhile, the feds were doing little to win the hearts and minds of many Kentuckians. Federal troops resorted to abrasive measures that were illegal or unconstitutional to maintain military control of the state. This included military interference with elections, such as prohibiting "disloyal" persons from voting.

By 1864, the Union army's ill treatment of civilians and Lincoln's inclusion of black freedom as a war aim "caused many formerly loyal Kentuckians to turn their sympathies against the federal government," writes Anne E. Marshall in Creating a Confederate Kentucky: The Lost Cause and Civil War Memory in a Border State.

Among those opposing federal policies was Brutus Clay, a U.S. congressman from Bourbon County, who was steadfastly against abolition and the enlistment of slaves into the Union army. (Brutus was brother to Cassius Marcellus Clay, who argued for emancipation and published an anti-slavery newspaper, The Lexington True American.)

During the debate on the 13th Amendment, Brutus Clay said: "If you take away from a man that which he considers to be justly his own, you make him desperate, and he will retaliate upon you. You can never by oppression make a man obey willingly the laws of his country. Act justly toward him, let him see he has a government which will protect him and he will love that government. But oppress and rob him, and he will despise and hate you."

Without Clay's vote, the 13th Amendment passed the U.S. House of Representatives in January 1865 — the climatic finale in Steven Spielberg's movie. The next month, the Kentucky legislature voted to reject it: 56-18 in the House and 23-10 in the Senate.

Slavery was still legal and visible in the commonwealth in 1865. One visitor traveling through the South that year noted that Louisville was the only place on the trip where slaves waited on him.

Nevertheless, the 13th Amendment was ratified by the necessary three-fourths majority of states and was officially adopted in December 1865. Kentucky, meanwhile, came to identify itself more with the Confederacy after the war than it did during the war. Between 1867 and 1894, Kentucky elected six governors who had been Confederates or Confederate sympathizers.

Kentucky did not move to ratify the 13th Amendment until state Rep. Mae Street Kidd, D-Louisville, one of three blacks then in the Kentucky legislature, filed a resolution to do so in 1976.

The resolution passed the Kentucky House by a 77-0 vote, and it passed the Kentucky Senate by a voice vote on March 18, 1976. The vote was symbolic — Kentucky's ratification wasn't needed for the amendment to be added to the U.S. Constitution — but it was a symbol with power.

Now, back to Mississippi. The Magnolia State ratified the 13th Amendment on March 16, 1995, but because the ratification document was never presented to the U.S. archivist, it was never considered official.

On Jan. 30 of this year, Mississippi finally sent a copy of its 1995 resolution to adopt and pass the 13th Amendment to the Office of the Federal Register.

A week later, Federal Register Director Charles Barth confirmed that he had received the paperwork, the Clarion-Ledger newspaper of Jackson, Miss., reported.

"With this action, the state of Mississippi has ratified the 13th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States," he wrote. (By Greg Kocher — gkocher1@herald-leader.com)

It's hard to imagine this shite! All these white bigots in Kentucky and Mississippi. Now we understand why Moscow Mitch McCONnel and Rand Paul keeps getting elected to Congress.

ReplyDeleteGOD is disgusted with Kentucky and Mississippi. You 'Christians' are starting to feel GOD's Wrath, but it's going to get much worse!

Don't get your panties in too much of a twist....self righteous virtue signaling can be hazardous to your health...

DeleteGood informative article well worth reading and gaining an understanding and insight into the history of the 13th Amendment.

ReplyDelete