From the Daily Journal of Northeast Mississippi, "The night in 1962 that shook the state and nation," by Errol Castens of the Daily Journal Oxford Bureau

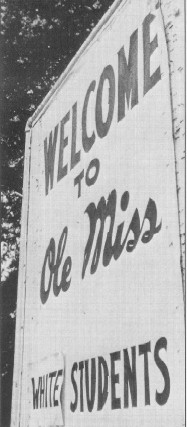

OXFORD - Fifty years ago tonight, a riot broke out over the pending admission of James Meredith as the first black student at the previously all-white University of Mississippi.

Late that Sunday afternoon, students gathered in front of the Lyceum, spurred by celebration of the previous night's gridiron victory in Jackson and a mix of anger, curiosity and fear over what lay ahead.

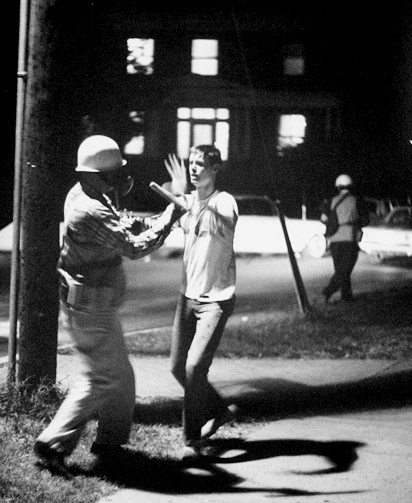

U.S. Marshals had circled the Lyceum, ostensibly protecting Meredith, who was assumed to be inside. (He was actually in his room at Baxter Hall.)

"The students were returning from the football game, and it was a pep rally," said Ed Meek, then an Ole Miss student and a stringer for several news organizations. While Meek and fellow stringer Larry Speakes were busy snapping photos and scribbling notes, most Ole Miss students left and were replaced by out-of-town protesters.

"I heard a wup-wup-wup, and a bottle went over my head and hit a Marshal," Meek said. "The crowd had changed, and when I turned around I didn't recognize a soul."

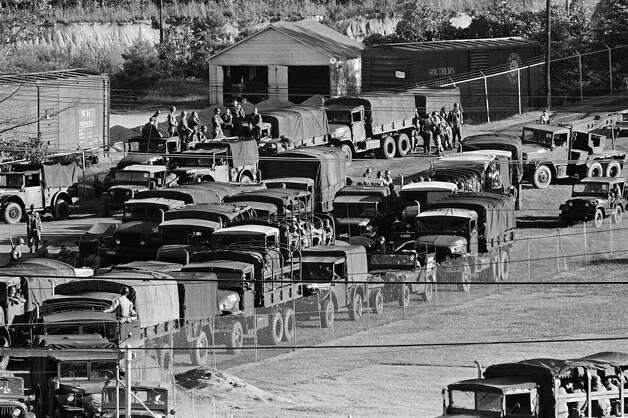

The riot that ensued has been called "the Battle of Oxford" and "the last battle of the Civil War." Its toll included two people dead and hundreds wounded, vehicles torched, buildings damaged and about 31,000 troops deployed.

It left the Ole Miss campus a war zone, Oxford an occupied city and Mississippi's leadership having encouraged open rebellion against the federal government.

The riot occurred after a U.S. Supreme Court order to admit Meredith, a 29-year-old black Air Force veteran, into the previously all-white university, and Meredith's arrival on campus.

While students were early taunters of the Marshals sent by President John Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, they soon were outnumbered.

"The rioters were nearly all from somewhere else," said Kaye Bryant. "I watched a charter bus from Alabama stop and a whole busload of armed men get off."

It was a confusing time. Bryant's then-husband was deputized as a sheriff's officer and tasked with keeping Meredith out of Ole Miss; later the same day he was federalized as a National Guardsman helping protect Meredith and enforce his admission.

Official defiance

Even after the court order, segregationist Gov. Ross Barnett repeatedly blocked Meredith's enrollment, secretly bargaining with the Kennedys to send armies so he could back down while saving face.

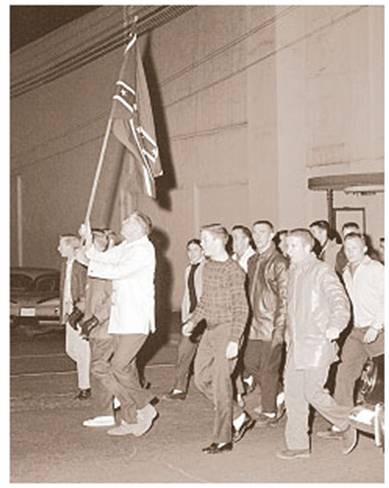

The Kennedys were trying to avoid using force that might trigger violent revolt. Ultimately, Barnett's address to the crowd during halftime of the Ole Miss-Kentucky football game in Jackson on Sept. 29 unleashed the rabble response and spurred the federal mobilization.

"I thought the stadium was going to come down," said Hassell Franklin, now of Houston and then a 25-year-old captain in Pontotoc's National Guard unit. "People were stomping and hollering, waving Rebel flags."

Claude Hartley, then captain of the Tupelo Guard unit, said commanders had been told they might be called upon to arrest the governor. When some men questioned whether they could fight against fellow Mississippians, Hartley said, "We're going over there to enforce the law, whether you agree with it or not."

Don Sheffield, then a 22-year-old manager of the Ole Miss football team, heard Barnett in Jackson.

"He was declaring that no university in Mississippi would be integrated as long as he was governor," he said. "I thought as I heard it, 'You crazy SOB, you don't care about me as a student if you're threatening to close the university.'"

All or none

During several years of Air Force service in Japan, Meredith had come to identify himself not primarily as a black man but as an American. Back in Mississippi, he would not accept second-class citizenship.

"Paradoxically, the concept of integration was never Meredith's goal. His objective was the total destruction of white supremacy," wrote William Doyle in "An American Insurrection."

Where many civil rights leaders pushed for incremental change, Meredith took an all-or-nothing approach. Doyle quoted him as saying, "My thing is the whole hog; either all of the citizenship rights, or none."

Unforgettable night

Those in Oxford during the riot will never forget it. Rioters used shotguns, rifles, a firetruck and a bulldozer to attack the Marshals. Soldiers nearly bounced out when their trucks ran over concrete benches thrown into the street, Franklin said, and though he was hit in the face with a lead pipe, he didn't realize he was injured until his gas mask filled with blood.

A French journalist and a local onlooker were the only two fatalities, although injuries were in the hundreds. Franklin is still amazed that the number was not far worse.

"That situation could not be rerun, in my view, and not get 50, 60, 75 people killed," he said. "These were wild people; they had lost their sense of reasoning."

The Rt. Rev. Duncan Gray Jr., retired Episcopal bishop of Mississippi and then-rector of St. Peter's Episcopal Church, was one of the only white clergymen in Oxford to openly support integration. He had gone to a friend's house to watch President Kennedy on TV.

"Just as soon as his speech was over, the network announced that a riot had broken out at the University of Mississippi and that two people had been killed," Gray recalled. "We got real concerned that Jim Silver (Ole Miss history professor and author of "Mississippi: The Closed Society") was one of them, knowing that he was out there."

Gray and two faculty friends went to campus and found the riot fully involved. They urged students to leave. Gray saw Gen. Edwin Walker, who had led the troops enforcing integration in Little Rock and who had retired to oppose integration, leading one portion of the mob near Ventress Hall. Gray climbed up on the Confederate statue to get his attention.

"I pled with him, 'Please, General Walker, ask them to stop all this,'" Gray said. "He turned and said, 'You make me ashamed to be an Episcopalian.'" Several people pulled Gray off the statue, but others rescued him as the mob headed into the Circle.

Psychological warfare was part of the mob mentality. Some guardsmen ripped off their name tapes after rioters tauntingly promised to look up their families.

Meek stayed out all night photographing and reporting, staying close to the ground to endure the tear gas that seemed to be everywhere. One of his photos from early the next morning showed columns of Jeeps extending over the horizon.

By daylight, the mob on campus had largely lost its energy.

"Most people were ready to get the hell out of there," Hartley said. Of about 50 people his soldiers had arrested, a grand total of two were from Lafayette County, and "only five or six" were from Mississippi.

"There were a lot of trashy people who just liked to do harm to other people and used the integration (issue) as an excuse," he said.

Gray went home around midnight, after the military was clearly in charge, but a surprise awaited him downtown the next morning.

"I got to the Square to go by the post office, and the town was full of soldiers," he said. "The conflict had moved from campus to downtown as these people were still coming in from out of town."

Meek went with Meredith and his U.S. Marshals escort to Meredith's first classes.

"Kennedy had made a really big deal that nobody was to interfere with the academic process - no pictures," Meek said, but the photojournalist in him couldn't resist. Carrying a camera under his coat, he snapped several that showed the emptied classroom after Meredith's arrival.

For weeks, Guard and regular Army units camped in and around Oxford.

"We stayed over there 30 days while Meredith was going to school. We patrolled and stayed ready if we were needed to maintain the peace," Hartley said.

Some units stayed through the end of the fall semester.

'Our two-by-four'

While nobody argues that Mississippi has left behind all its racist past, a lot has changed since the Battle of Oxford. Nearly a quarter of Ole Miss students are from racial minorities, including 16.5 percent black. The Associated Student Body President and Homecoming Queen are both African-American. Mississippi has more black elected officials than any other state.

U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, who visited Ole Miss on Thursday, said the university and the nation had to endure trauma to correct a fundamental flaw.

"This was never a question of doing what was easy; it was a matter of doing what was right," he said. "We needed to carry out the Supreme Court's decision, and to affirm that the United States was a nation governed by laws unbound by the politics of convenience or the pressures of the day."

History professor Charles Eagles, author of "The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss," urges the university to teach more about the context of integration.

"Why here? Why 1962?" he said Monday at the Overby Center. "A lot of people treat the riot ... as something that just emerged and then went away."

Ole Miss, Eagles said, reflected Mississippi's widespread racial oppression wrapped in sentimentality, and weak university leadership during the civil rights era helped segregationist state leaders maintain its insularity.

"We have made progress," he said. "Is anybody concerned about why we had to make progress? About what came before the progress? We can celebrate progress once we acknowledge error. We can claim redemption once we acknowledge sin."

Chancellor Dan Jones says the commemoration of 1962's events is a chance to do just that.

"As we look back, we acknowledge the years of injustice endured by Mr. Meredith and countless others, express regret and offer our apology for the injustice," Jones said. "We also take this opportunity to recommit ourselves to open doors of opportunity to everyone regardless of race or ethnicity."

Kaye Bryant long pondered how Mississippi's passive majority - people by many measures generous, pious, law-abiding and patriotic - were so blind to the evils of segregation and the cruelties that enforced it.

"All our thinking got turned completely around," she said.

Bryant found her answer in an old tale about a balky mule known to oppose the farmer's every effort to make him useful. When a neighbor later noticed the mule had become a model of cooperation, a transformation that the farmer explained as having hit the mule with a two-by-four "to get his attention."

"After that, he settled right down," she said.

The integration of Ole Miss was followed a few years later by the court-ordered integration of public schools all over Mississippi. Community leaders in Oxford set about quickly to pursue a peaceable joint path.

"We never had a single problem, because somebody had gotten our attention, and we didn't want to go there again," said Bryant. "James Meredith was our two-by-four." (source: DJournal of Northeast Mississippi)

No comments:

Post a Comment