From the New York Times, "Liberation as Death Sentence," by Jennifer Schuessler, on 10 June 2012 -- When Civil War History published a paper this spring raising the conflict’s military death toll to 750,000 from 620,000, that journal’s editors called it one of the most important pieces of scholarship ever to appear in its pages.

But to Jim Downs, an assistant professor of history at Connecticut College and the author of the new book “Sick From Freedom,” issued last month by Oxford University Press, that accounting of what he calls “the largest biological crisis of the 19th century” does not go nearly far enough.

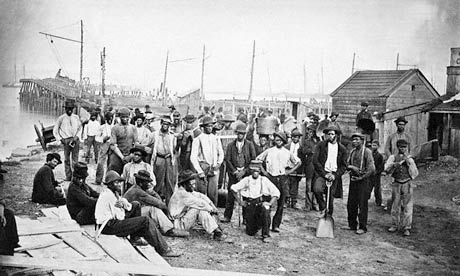

To understand the war’s scale and impact truly, Professor Downs argues, historians have to look beyond military casualties and consider the public health crisis that faced the newly liberated slaves, who sickened and died in huge numbers in the years following Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

“We’re getting ready to celebrate 150 years of the movement from slavery to freedom,” he said in a recent interview at a cafe near his apartment in Chelsea. “But hundreds of thousands of people did not survive that movement.”

“Sick From Freedom,” at 178 pages (not counting 56 pages of tightly argued footnotes), may seem like a bantamweight in a field crowded with doorstops. But it’s already being greeted as an important challenge to our understanding of an event that scholars and laypeople alike have preferred to see as an uplifting story of newly liberated people vigorously claiming their long-denied rights.

“The freed people we want to see are the ones with all their belongings on the wagon, heading toward freedom,” said David W. Blight, a professor of history at Yale and the director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition. “But the truth is, for every person making it there may have been one falling by the way.”

Professor Downs, 39, is part of a wave of scholars who are sketching out a new, darker history of emancipation, Professor Blight said, one that recognizes it as a moral watershed while acknowledging its often devastating immediate impact. And the statistics offered in “Sick from Freedom” are certainly sobering, if necessarily tentative.

At least one quarter of the four million former slaves got sick or died between 1862 and 1870, Professor Downs writes, including at least 60,000 (the actual number is probably two or three times higher, he argues) who perished in a smallpox epidemic that began in Washington and spread through the South as former slaves traveled in search of work — an epidemic that Professor Downs says he is the first to reconstruct as a national event.

Historians of the Civil War have long acknowledged that two-thirds of all military casualties came from disease rather than heroic battle. But they have been more reluctant to dwell on the high number of newly emancipated slaves that fell prey to disease, dismissing earlier accounts as propaganda generated by racist 19th-century doctors and early-20th-century scholars bent on arguing that blacks were biologically inferior and unsuited to full political rights.

Instead, historians who came of age during the civil rights movement emphasized ways in which the former slaves asserted their agency, playing as important a role in their own liberation as Lincoln or the Union army.

“For so long, people were afraid to talk about freed people’s health,” Professor Downs said. “They wanted to talk about agency. But if you have smallpox, you don’t have agency. You can’t even get out of bed.”

Professor Downs first became interested in the health of newly liberated slaves when he was a graduate student at Columbia University with a job as a research assistant in the papers of Harriet Jacobs, the author of the 1861 autobiography “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” and a vivid chronicler of the often abysmal conditions in the “contraband camps” where escaped slaves congregated during the war and in settlements of freed people more generally after it. The papers were full of heart-wrenching encounters with sick and dying freed people — references that he noticed were strikingly absent in recent scholarship.

As he developed the topic into his dissertation, Professor Downs recalls sparring with his adviser, Eric Foner, the author of the classic book “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Business, 1863-1877.”

“He would joke: ‘Look in my index. You don’t even see smallpox,’ ” Professor Downs said.

But as he sorted through the little-explored records of the medical division of the Freedmen’s Bureau and other archives, he found reams of statistical and anecdotal accounts of sick and dying freed people, whose suffering was seen by even some sympathetic Northern reformers as evidence that the race was doomed to extinction.

Meanwhile tallies of the smaller number of white smallpox victims were kept only lackadaisically and eventually crossed out all together — evidence, he argues, that officials were eager to see the outbreak as a “black epidemic” not worth bothering about. (By contrast a cholera outbreak in 1866 that mainly affected whites was vigorously combated, he notes.)

Professor Downs also found a medical system that was less concerned with healing the sick than with separating out healthy workers who could be sent back to the fields, and then closing the hospitals as quickly as possible.

In an e-mail Professor Foner praised “Sick From Freedom” as offering “a highly original perspective” that “deserves wide attention.” And Professor Downs makes no bones about wanting to place health issues at the center of multiple scholarly conversations about the war and its aftermath.

“I wanted to say, ‘You’re not allowed to do the history of labor or the history of the family or the history of citizenship unless you go through my book,’ ” he said. “I wanted to be able to tell a story about these people’s lives that wouldn’t get pushed aside as melodrama.”

He is also not shy about drawing out his work’s contemporary relevance. His dissertation included an epilogue about AIDS, another epidemic, he said, that broke out shortly after a moment of liberation (in this case of gay people), was blamed on the victims and was largely ignored by the federal government. (He dropped the point from the book, which instead ends with an epilogue showing how policies developed in the post-Civil War South were exported to the Western frontier, with similarly devastating health consequences for American Indians.)

Professor Downs also sees parallels with the current health care debate. “Freed slaves,” he writes in the book, were “the first advocates of federal health care” — a statement that could be read from the left as an example of early black political activism, or from the right as an instance of newly liberated people immediately asking for a government handout.

That second reading was one he initially worried about, Professor Downs said. But he ultimately just let the historical chips fall where they may.

“I’ve been alone with these people in the archives,” he said. “I have a responsibility to tell their stories.” (source: New York Times)

No comments:

Post a Comment