Civil War Ruins in Norfolk, Virginia

From the New York Times Opinionator Disunion, "Harriet Jacobs’s First Assignment," by Scott Korb, on 6 September 2012 -- Harriet Jacobs arrived in Washington in June 1862, she later reported, “without molestation.” Lots of people traveled in and out of the capital at the time, but for Jacobs it was quite a feat. By then a correspondent on assignment for William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator, Jacobs was a former slave and author of the book “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” which she wrote under the assumed name Linda Brent. Traveling through Maryland, where slavery was still legal, and Pennsylvania, where anti-black animus still ran high, would have made for tough going for most free blacks. Even fewer could have taken in the squalor that Jacobs found among the thousands of refugees from the South now huddled in the capital.

Then again, Jacobs wasn’t most people. As she recounted in “Incidents,” to escape the sexual predations of her master in Edenton, N.C., and his constant threat to sell her, Jacobs hid first in a swamp and then, for seven years, in a garret in her grandmother’s house. In June 1842 she escaped on a boat to Philadelphia and then traveled on to New York.

At the urging of several friends within the abolitionist movement, Jacobs published “Incidents” in early 1861. A January 1861 review by William C. Nell, a black Bostonian, in the Liberator said the book “presents features more attractive than many of its predecessors” because “this record of complicated experience in the life of a young woman, a doomed victim to America’s peculiar institution … surely need not the charms that any pen of fiction, however gifted and graceful, could lend.”

Jacobs encountered Garrison in June 1862 at the yearly meeting of the Progressive Friends of Longwood, Pa., just months after President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill abolishing slavery in the capital. At Longwood, Garrison led the drafting of a further appeal to the president calling for the immediate emancipation of all slaves, a move the Progressive Friends believed would produce the quickest end to the war.

As the meeting broke up, Garrison enlisted Jacobs to travel to Washington, “where the shackles had just fallen,” she wrote, and deliver on his “request of a line on the condition of the contrabands.” The report, totaling about 4,000 words, would appear in the Sept. 5, 1862 issue of the newspaper.

Her work in the capital, the first she’d taken on as a journalist, began the following morning with a visit to Duff Green’s Row, the government headquarters for newly freed blacks and refugees from the South. Jacobs was at first horrified to discover men and women and children – former slaves like herself – “all huddled together, without any distinction or regard for age or sex.” Here, she said, were the pitiful, the “hungry, naked and sick” from Matthew’s Gospel – many dressed in rags and with nowhere to sleep but the bare floor – truly the least brothers and sisters of a nation at war. “Those tearful eyes often looked up to me with the language,” she wrote, “‘Is this freedom?’” Jacobs found measles, diphtheria, scarlet and typhoid fever; some days saw as many as 10 deaths among the refugees.

And still, the following day and the one after that more men and women and children would come to take the places of the dead, because this was freedom. They would arrive all day and through the night, each newcomer recorded by a superintendent who seemed able to do little more for them, Jacobs reported, than take their names. With no one directly charged with the care of the refugees and “nothing at hand,” she wrote, “to administer to the comfort of the sick and dying,” Jacobs could arrive at only one conclusion: “I felt that their sufferings must be unknown to the people.”

Jacobs found able-bodied men hiring themselves out at just $10 a month; single women were paid $4, and a woman with a child or two was promised between $2.50 and $3. Despite claims to the contrary, Jacobs reported, these people would “work and take care of themselves.” She certainly had. Finding a similar desire to work among the refugees across the Potomac in a “strongly secesh” Alexandria, Va., Jacobs reported anxiety among the laboring refugees that their pay, which was very slow in coming, was actually being sent to their former masters.

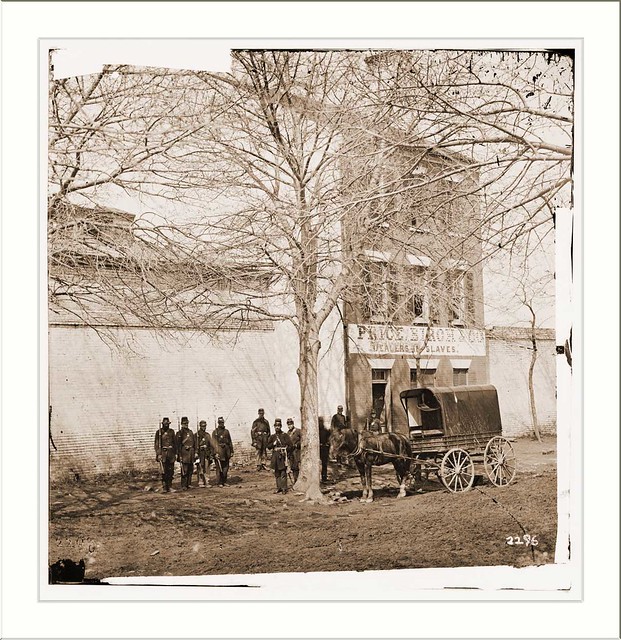

Birch’s Slave Pen in Alexandria, Va. (Library of Congress)

Shortly after Jacobs arrived in Washington a new – and by her initial assessment, much more competent – superintendent was hired to oversee the flood of black refugees into the capital. Danforth B. Nichols was a Methodist minister affiliated with both the American Missionary Association and the recently organized National Freedmen’s Relief Association of the District of Columbia. According to Jacobs, he “laid down rules, went to work in earnest pulling down partitions to enlarge the rooms, that he might establish two hospitals, one for the men and another for the women.” This pleased Jacobs’s Victorian sensibilities. Nichols, Jacobs believed, “seemed to understand what these people most needed.” (Hired in May 1863 to fill a similar position in Arlington, Va., Nichols’s reputation would fall. A former slave, Lewis Johnson, who knew Nichols in Arlington, would later testify: “Mr Nichols was not kind to the people under him in the camp; he used to knock them about and kick them right smart. … I can not tell the number of persons he used to abuse, but there were a great many.”)

Jacobs’s article was more than a report, though — it was a plea to her Northern readers’ consciences. She appealed to their vanity as well: Whereas the Freedmen’s Relief Association, “a small society in Washington,” was doing all it could to provide cots and mattresses for the refugees, Jacobs reminded her readers, “Washington is not New England.”

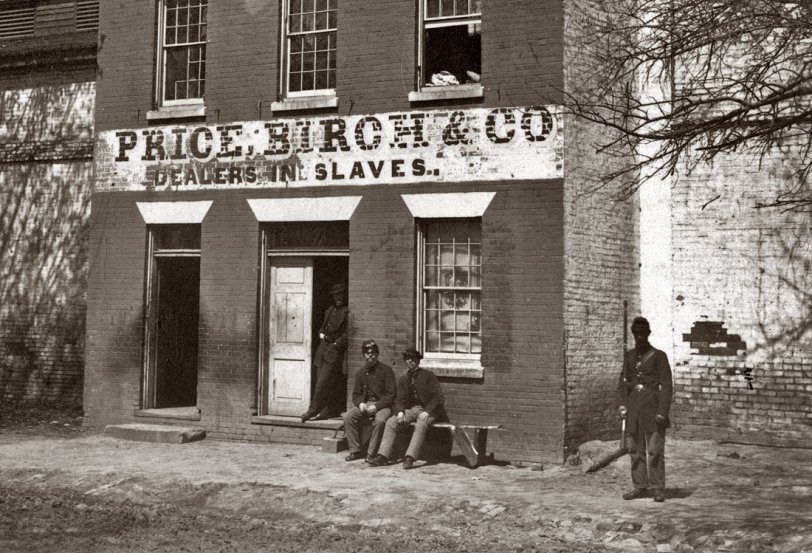

Alexandria, Virginia Slave Pen Interior

After all, New England had provided both Hannah Stevenson, the first Massachusetts woman to volunteer during the war, and Julia Kendall, who responded to a call from Stevenson for “superior nurses” to join the effort in Washington. Making rounds at Duff Green’s Row, Kendall and Stevenson, whose names, Jacobs said, would “be lisped in prayer by many a dying slave,” were the first white women she had encountered among the refugees – “except those who had come in to hire them.”

Even before her article appeared, Jacobs wrote dispatches to individual Northern readers and friends. A single letter from Jacobs, she wrote, requesting goods from a woman in New York had resulted in the donation of “an immense box” and a total transformation of the situation for the refugees:

Before the sun went down, those ladies who have labored so hard for the comfort of these people had the satisfaction of seeing every man, woman and child with clean garments, lying in a clean bed. What a contrast! They seemed different beings. Every countenance beamed with gratitude and satisfied rest. To me, it was a picture of holy peace within. The next day was the first Christian Sabbath they had ever known. One mother passed away as the setting sun threw its last rays across her dying bed, and as I looked upon her I could but say – “One day of freedom, and gone to her God.”

Jacobs moved freely among Washington and Alexandria and even Arlington Heights, “Gen. Lee’s beautiful residence, … so faithfully guarded by our Northern army” and also home to refugees from the South. Alexandria, though, was where she directed most of her attention, jotting down descriptions of former slaves now behind Union lines, as well as the opportunities that Alexandria’s refugees presented for Northern philanthropy.

Alexandria’s old Washington School House, constructed in 1785 with an endowment from George Washington, was, to Jacobs, “the most wretched of all the places.” It was used during the war as a women’s hospital and later a school, and Jacobs found refugees there “from infancy to a hundred years old.” Six or seven blocks to the west was Birch’s slave pen, requisitioned by the government as a residence for refugees and a prison for secessionists – “all within speaking distance of each other.” Another residence was home to any number of other destitute people who, like those housed in the slave pen and the old school house, were supplied with clothing given to Jacobs by women belonging to freedmen’s organizations in the North. These women “clothed the naked, fed the hungry,” Jacobs wrote.

By the time Jacobs arrived in Alexandria, there were already three freedmen’s schools established to teach an “eager group of old and young striving to learn their A, B, C, and Scripture sentences.” In her report, though, Jacobs looked north for more female teachers, who unlike men, she believed, “could do something more than teach them their A, B, C. They need to be taught the right habits of living and the true principles of life.” In time, Jacobs would open her own school in Alexandria – the Jacobs Free School, where she would be known as Mrs. Jacobs – bringing along her daughter Louisa and also recruiting two black women from Massachusetts, the sisters Eliza Mariana and Sarah Virginia Lawton, daughters of the activist Edward B. Lawton.

After begging her readers for patience for those they might find “so degraded by slavery that they do not know the usages of civilized life,” Jacobs’s final plea was on behalf of the many orphans she encountered in her travels. Her model of charity was a refugee herself. A mother of two had just died, Jacobs reported, when a woman approached her in the hospital begging to adopt one of the children. She came with five children of her own. “What can you do with this child,” Jacobs asked her, “shut up here with your own? They are as many as you can attend to.”

Tearfully, the woman told Jacobs: “The child’s mother was a stranger; none of her friends cum wid her from de old place. I took one boy down on de plantation; he is a big boy now, working mong de Unions. De Lord help me to bring up dat boy, and he will help me to take care dis child. My husband work for de Unions when dey pay him. I can make home for all. Dis child shall hab part ob de crust.”

Jacobs made the arrangements. And then came her scold in the paper: “How few white mothers, living in luxury, with six children, could find room in her heart for a seventh, and that child a stranger!”

Jacobs’s bet with her September report was that some white mothers would take up this charge and find room for the orphans, “from eight years old down to the little one-day freeman.” She knew that many more would contribute to institutions set up throughout the North and South to care for them. Jacobs would return to Alexandria and renew this plea. She would return to bring relief throughout the war – making a home for herself and all comers – as the numbers of refugees swelled. She would return to write, and this time she would return under her own name. (source: New York Times Opinionator Disunion)

No comments:

Post a Comment