From the New York Times Disunion, "When Cotton Was King," by Gene Dattel, on 26 March 2011 -- COTTON, SLAVERY, THE CIVIL WAR -- Looking forward from the dawn of the American republic, it was easy to assume that slavery would soon fade away. Slaves were primarily used to produce staple crops like tobacco, rice, indigo and sugar, all of which were in decline under competition from the Caribbean. Without these, slavery could not survive.

“Slavery in time will not be a speck in our country,” opined Oliver Ellsworth, a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Indeed, it was that assumption that allowed the anti-slavery delegates to cede easily to a compromise in writing the Constitution: slavery would never be mentioned, but it would be given legal protection. Founding a nation, Ellsworth and others decided, was more important than eradicating a “moral anachronism.”

That assumption, however, proved disastrously wrong, thanks to a new, much more valuable cash crop then still on the horizon: cotton. Over the next 70 years this new cash crop would revolutionize the American economy and breathe new life into the institution of slavery. On the eve of the Civil War, far from facing imminent decline, slavery, and the cotton economy that depended on it, was going strong.

In 1787, there was virtually no cotton grown in America. Two things, however, quickly changed that. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin allowed cotton production to go from a process limited by manual labor to an industrial machine, allowing a person to “clean” 50 pounds, rather than one pound, of cotton a day. And of course, the cotton gin didn’t remove manual labor from the process; it just shifted it. In fact, this labor-saving device extended slavery by creating a labor shortage in the cotton fields.

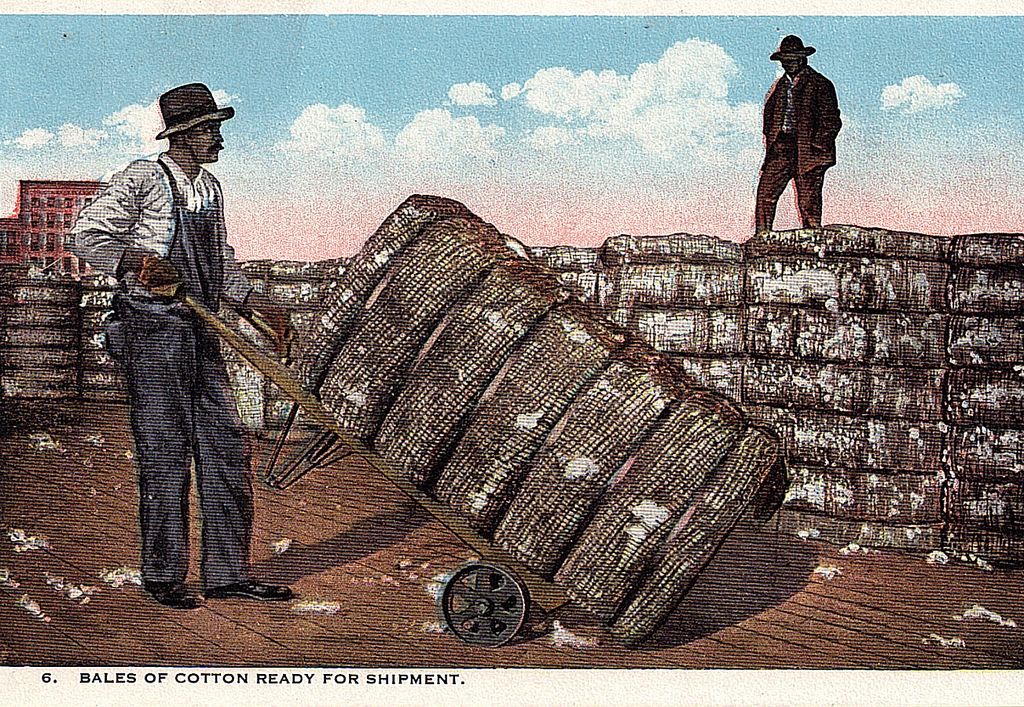

The mass production of cotton was accompanied by a dramatic 90 percent drop in the price of a cotton textile garment. This in turn led to a consumer revolution whose raw material was slave-produced cotton – 80 percent of which was produced in the South. As a result, American cotton production exploded from almost nothing in 1787 to over 4.5 million bales, at 500 lbs. a bale, by 1860. On the eve of the war, cotton comprised almost 60 percent of America’s exports.

Slavery expanded accordingly. The number of slaves increased from 700,000 in 1787 to over 4 million on the eve of the American Civil War; approximately 70 percent were involved in some way with cotton production. Indeed, so closely tied were cotton and slavery that the price of a slave directly correlated to the price of cotton (except during years of excessive speculation). Interestingly, slaves were considered too valuable in the cotton states to be used for dangerous work in the malarial swamps that bordered levees and canals. Irish immigrants were the truly expendable class.

The expansion of cotton meant the geographic expansion of slavery as well. In its wake, cotton dragged its enslaved laborers to the rich states in the country’s then-southwest where it could be grown more easily. It was “as if this plant-king,” wrote historian W. B. Hammond, “were literally leading the human captives in his train.” Gavin Wright, an economic historian, observed that the “slave economy ultimately came to resemble the geography of natural cotton-growing regions.” In other words, slavery only spread where cotton could be grown. Harriet Beecher Stowe captured this well in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” when slaves were “sold down the river” to work on cotton plantations.

Increased cotton production, not optimum efficiency or profit, became an obsession. A Northern traveler in 1834 noticed this singular goal: “To sell cotton in order to buy negroes – to make more cotton to buy more negroes, ‘ad infinitum.’” Today, we call this leverage. Although risky, cotton’s revenue stream and collateral made credit available, which in turn facilitated more production. During the antebellum period, financing utilized tragic human collateral to expand a horrific institution.

As one might expect, if the price of cotton went down, so did the price of a slave. Or, as Stowe astutely asserted in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” if ”something would bring down the price of cotton once and forever, … [it would] make the whole slave property a … [burden] in the market.”

One of the main arguments made by Southern sympathizers and other critics of Abraham Lincoln, at the time and in the 150 years since, was that the Civil War was unnecessary; like the founders, they have argued that slavery would have died out on its own. This was, too, a core assumption of many Republican leaders at the time: that if the expansion of slavery could be checked, then it would eventually wither away.

But nothing about the cotton economy of 1861 pointed that way. On the eve of the Civil War there was no perceived threat to the existence of slavery; on the contrary, production levels had never been higher, and despite occasional drops in price, cotton was proving a reliably stable profit engine. Indeed, slave-produced cotton had become a formidable political and still-growing economic force: as early as 1838, a partner of Nicholas Biddle, America’s finance king, paid homage to cotton as a weapon: “Cotton … will be much more effective in bring … [England] to terms than all the disciplined troops America could bring into the field.” In 1858 James Henry Hammond, a senator from South Carolina, asked, “Would any sane nation make war on cotton? … No power on earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is King.” The ubiquitous faith in cotton made slavery seem impregnable.

Not only Southerners, but Northerners as well understood the consequences of the linkage between cotton and slavery – much better than their revolutionary-era predecessors. William Henry Seward, an anti-slavery unionist and Lincoln’s secretary of state, described this catastrophic miscalculation. The founding fathers, he wrote in 1860, “did not see … the reinvigoration of Slavery consequent on the increased consumption of cotton.” In 1861, the real and imagined rule of King Cotton meant that slavery had a firm economic hold on the American psyche – North and South. Slavery, realists understood, would not die willingly. (source: New York Times Disunion)

thank you for the update, it's quite good.

ReplyDeletewww.n8fan.net