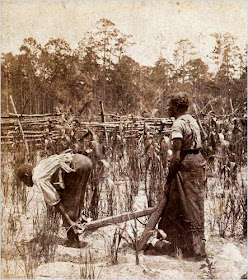

From the New York Times, on 22 April 2001, "Seeds of History: The expertise of African slaves in growing rice played a crucial role in the American South," by Drew Gilpin -- In low-country South Carolina, American slavery assumed a distinctive form, one that has captured the attention of generations of historians. Between the end of the 17th century and the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of people of African descent toiled in swamps, ditches and fields cultivating rice, a crop that by the time of the American Revolution had created a planter aristocracy wealthier than any other group in the British colonies. The high concentrations of slaves in rice-growing areas produced as well a black culture that remained closer to its African roots than that of any other North American slave society. Yet even in South Carolina, where they were a majority of the population, blacks have remained underrepresented in the historical record, partly because they were unable to leave the rich written legacy that immortalized their owners, partly because historians have failed to look closely enough at the evidence that has survived.

In ''Black Rice,'' Judith A. Carney, a professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles, finds new ''ways to give voice to the historical silences of slavery.'' Exploring crops, landscapes and agricultural practices in Africa and America, she demonstrates the critical role Africans played in the creation of the system of rice production that provided the foundation of Carolina's wealth.

Carney challenges conventional histories, which describe Europeans adapting an Asian crop to American uses. Arguing persuasively that highly sophisticated forms of rice culture from West Africa preceded the arrival of any knowledge from Asia, she carefully traces the variety of production systems used by Africans in different environments and landscapes, including the elaborate construction of canals and dikes in coastal swamps. The existence of these complex adaptations was ignored by European observers all too ready to dismiss the possibility of technological achievement among African peoples. The ''denial of African accomplishment in rice systems,'' Carney writes, ''provides a stunning example of how power relations mediate the production of history.''

Not until well into the 20th century did changing assumptions about race prompt revisions to this story. Since the publication of Peter Wood's pathbreaking ''Black Majority'' in 1974, historians have recognized a link between African rice cultivation and Carolina's economic success. But Carney's richly detailed analysis gives this connection real specificity.

In order to understand the role of Africans in rice history, Carney argues, it is necessary to think of rice as a ''knowledge system'' -- not just a plant or a seed but an entire complex of techniques, technology and processing skills. Africans imported as slaves into Carolina possessed this knowledge, and used their understanding to guide phases of evolution in American rice production.

Thus, after a vast increase in importations of slaves between 1720 and 1740 provided the necessary labor, Carolina rice cultivation, which had begun with upland or rain-fed culture, shifted to higher-yielding inland swamps. The newly arrived Africans created embankments, sluices and canals almost identical to patterns of West African mangrove rice production. With another influx of slaves after 1750, cultivation moved to still more productive tidal flood plains, which required such a large-scale deployment of floodgates, canals and ditches that rice fields became, in one planter's words, a ''huge hydraulic machine.'' This transition, Carney writes, depended on ''the large number of slaves imported directly from the rice area of West Africa who possessed knowledge of the crop's cultivation.''

Carolina planters even knew which African ethnic groups were expert in rice growing and explicitly favored them in their purchases of new slaves. A newspaper in Charleston, for example, advertised the sale of 250 slaves ''from the Windward and Rice Coast, valued for their knowledge of rice culture.''

The knowledge system Carney describes called for different roles and distinctive kinds of expertise for men and women, and these aspects of rice culture were also transported to the New World. Women played a critical part in seed selection, sowing, hoeing and processing of rice. The importance of these skills enabled slave traders to command higher prices for women in Carolina rice-growing areas than in other American slave markets.

The Carolina rice kingdom, the foundation of power in a state that would eventually lead the South out of the nation, came into being because African slaves had mastered -- and shared -- the techniques necessary for growing rice seeds in standing water. ''Why,'' Carney asks, ''would West African slaves transfer to planters a sophisticated agricultural system . . . that would in turn impose upon them unrelenting toil throughout the year?'' The knowledge of rice cultivation, she concludes, provided slaves arriving in South Carolina with a crucial negotiating tool, enabling them to bargain for labor arrangements that guaranteed them greater autonomy than in any other Southern agricultural environment.

In cotton-growing areas a system of gang labor prevailed that required unremitting work from dawn till dusk. But on South Carolina rice plantations task labor was the rule. Once their tasks were accomplished, slaves could turn to their own gardens, or manage their own time in other ways. Task labor introduced a degree of freedom into slavery's oppression.

But Carney is careful not to be too celebratory about the leverage Africans achieved as a result of their knowledge and skill. As rice became a commodity in high international demand, even the structures of the task system could not protect Carolina slaves from almost ceaseless labor.

This detailed study of historical botany, technological adaptation and agricultural diffusion adds depth to our understanding of slavery and makes a compelling case for ''the agency of slaves'' in the creation of the South's economy and culture. But Carney also illuminates another of the almost limitless ironies of Southern history. The knowledge and creativity of Africans created an agricultural system in South Carolina that was based firmly on their own enslavement and exploitation.

[Drew Gilpin Faust's most recent book is ''Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War.'' (source:New York Times )]

No comments:

Post a Comment