From Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform, as reported in the Mobile Register, on 11 December 1994, by Harvey H. Jackson III, "White Supremacy, Honest Elections and the New Constitution, One and Inseparable."

That was the slogan printed across envelopes sent out by the Alabama Democratic State Campaign Committee in the fall of 1901. Inside were letters urging the faithful to use their influence in the election scheduled for Nov. 11 of that year.

The time had come for Alabamians to vote on the constitution that 155 delegates, mostly Democrats, had written that summer. Now, the party wanted the constitution ratified, and it was doing everything in its power to see that it was done.

The constitution reflected the uncertainties of the time, and many Democrats believed that their survival as a party and a people depended on its approval. Since the Civil War, they had struggled against what must have seemed an almost endless string of enemies and obstacles. Now, victory was close. But so was defeat.

To understand who these Democrats were and why the constitution was so important to them, you have to go back to the years immediately following the Civil War. During Reconstruction, a coalition of Alabama Unionists and anti-secessionists, free blacks and some key Northern transplants united under the Republican banner. They overwhelmed their opposition, many of whom were disfranchised ex-Confederates, and took control of the state. Then they wrote, and in 1868 they ratified, a constitution that gave them the authority to govern Alabama as they wished.

But Republican rule was short-lived. Conflicting ambitions divided the party, and revitalized Democrats soon struck back. Branding native Alabama Republicans as "scalawags," condemning outsiders as "carpetbaggers" and issuing dire warnings about "black rule," Democrats offered themselves as true Southerners who would end corruption in Montgomery, put the debt-ridden state on sound financial footing and restore the white man to power.

When these promises did not sway voters, fraud, intimidation and violence did. By the mid 1870's, the Democrats were in power and Alabama was "redeemed."

The victors were the "Bourbons," men of property and status who felt they had suffered under Republican rule and who wanted to be sure that they would not suffer again.

Once in office, they did what the Republicans had done. In 1875, they confirmed their victory and secured their power with their own constitution.

Among their many goals was to keep Bourbon money in Bourbon pockets. They limited the state’s taxing power, abolished boards and offices created by the Republicans (including the board of education), allowed the state debt to be settled in ways still not fully understood today, and prohibited state support for projects such as river improvement and railroad construction.

The Bourbon constitution of 1875 was a victory for prosperous rural and small-town Alabamians who did not want to pay taxes to improve the lives of those less fortunate than themselves and who did not want to finance commercial development that did not benefit them directly. In particular, it was a victory for planters and merchants who dominated the Black Belt economy and government and who expected to maintain that domination (along with their influence on the state level) by controlling the black vote in their region.

In the years that followed, it seemed that the constitution of 1875 had accomplished just what the Bourbon Democrats intended. Although these were not the best of times for the cotton economy, politically powerful, propertied Alabamians generally fared well, and their hold on state government seemed secure.

But there was opposition. Some circles blamed the absence of industrial progress on the prohibition of state aid for transportation projects. Educators denounced the low tax ceilings that kept schools poor. Reformers decried the lack of governmental services for people.

Legislative watchdogs noted that the people’s representatives devoted far more time to local and private bills than they did to matters that affected the state as a whole.

These critics, however, were no real threat to Bourbon control. The real threat came from another quarter.

While planters and merchants were doing well enough, times were not good for Alabama’s small farmers. Postwar taxes, a nationwide financial panic in the 1870s, high interest rates and a general decline in cotton prices drove many once-independent yeomen off their land and into sharecropping and tenant farming, where landless blacks were already.

Even those who held on to their farms struggled to survive, and when old solutions such as hard work and increased yield only drove prices lower, they began to look elsewhere for help.

What many found was the Farmer’s Alliance.

Originating in Texas, the Alliance reached Alabama by the 1880s and was growing rapidly. At first, it focused on education and economic cooperation. It stayed out of politics, and its members seemed content to work within the Democratic Party to improve their lot.

But Bourbon planters and merchants were hardly sympathetic to Alliance ideas, such as farmers’ cooperatives, that would reduce the power of the middle man in cotton commerce or to suggestions that the state should intervene on the farmer’s behalf with debt relief. The Democratic Party might help the farmer, but the Bourbon Democrats who controlled the party would not.

So Alabama farmers sought and found a champion - Commissioner of Agriculture Reuben F. Kolb, who had gained fame and fortune developing the "Kolb Gem" watermelon.

Though of the planter class, Kolb emerged as a powerful spokesman for farmer interests. Like the farmers who rallied to him, Kolb hoped to work for reform within the Democratic Party. But as Bourbon opposition grew, so too did rumors of rebellion within the party.

What Bourbons heard, or at least thought they heard, was that white Alliancemen might join members from the Colored Alliance in a coalition that could dominate the party and state. Such an arrangement might encourage black voters in the Black Belt to defy planter authority and take control of county governments. Once in power, Alabama’s new leaders would find it only natural to confirm their authority with a new constitution, a document the Bourbons feared would be anything but favorable to their interests.

Frightened at this prospect, Bourbons reminded potential defectors that the "only place for a white man was the Democratic Party," and raised the specter of "black rule" if a third party was formed. It seemed to work.

In 1890, Kolb sought the Democratic nomination for governor, but lost to the conservative candidate, Thomas G. Jones. Accepting defeat, Kolb and his followers campaigned loyally for the party’s choice and the party’s choice won easily.

But Alliance-endorsed candidates captured a majority of seats in the Alabama House, and emerged from the election as an influential minority in the Senate. Everyone knew that the contest for governor in 1892 would be critical for Bourbons and Alliancemen alike.

Though it was custom for a governor to be given his party’s nomination for a second term, Kolb went against tradition and challenged Jones in 1892. But the Bourbons controlled the state Democratic Executive Committee, which decided which delegates would be seated at the convention. To no one’s surprise, the majority of the approved delegates were Jones supporters.

Kolb’s outnumbered forces tried without success to get some reforms adopted, including a primary to nominate candidates. Frustrated, they left the convention and met as the "Jefferson Democrats."

The defectors naturally nominated Kolb, who excited his supporters (and terrified the Bourbons) with an acceptance speech that promised prison reform, advocated "better schools and better roads," and called for the election of legislators who "would secure a fair ballot and an honest count."

That last pledge was not well received among the Bourbons. With the white Democrats split, they knew that the black vote was the key to victory. They also knew that if black voters were allowed to cast their ballots without interference, Kolb and the "Jeffersonian Democrats" could well carry the day.

The stage was set for one of the most bitterly contested and corruptly decided elections in Alabama history.

In some counties, the black vote was free, and both parties campaigned for it. Things were different in the Black Belt. Realizing that victory for the "white man’s party" depended on the black vote, Black Belt Democrats used fraud and intimidation to bring in huge majorities for Jones. The Black Belt delivered the Democrats a margin of more than 30,000 over the Jeffersonians. Statewide, Jones won by less than 12,000 votes. Fifteen Black Belt counties gave him the victory. With no constitutional or legislative means to challenge the election, Kolb had no choice but to accept defeat.

But the Bourbons wanted to be sure that Alliance supporters would not return to fight another day. The following year, conservatives passed an election law that complicated the voter registration process and increased the power of local election officials to determine who was qualified to cast a ballot. The provision that registration would take place only in May, one of the busiest months in the farmer’s year, underscored just what the Bourbons intended. It was the beginning of a Bourbon campaign to take the ballot out of the hands of those who threatened Bourbon rule.

It worked. Throughout the state, voter rolls shrank as poor farmers, white and black, failed to register.

Not all Bourbons were comfortable with this. Black Belt planters wanted to keep black voters registered so they might have those votes to use as they wished. Any effort to disfranchise black voters threatened their power. They also feared that a decline in registered voters would lead to the reapportionment of the Legislature and that Black Belt influence would be reduced even further.

So it is not surprising that when Bourbons began talking of a new constitution that would disfranchise black voters and guarantee that no black-white coalition would defeat the Democrats, Black Belt leaders were less than enthusiastic. Outside the Black Belt, conservative Democrats had concluded that "honest elections" (elections they could win) were possible only if "corruptible voters" (those who might someday vote against them) were removed from the rolls.

They were not troubled by the fact that they seemed to be saying that the best way to keep the white man from stealing the black man’s vote was to take the black man’s vote away from him. Bourbon Democrats knew what they wanted to do, and intended to do it.

There were obstacles, however.

Black Belt leaders still had to be convinced that their political power would not diminish with black disfranchisement. They also had to be assured that their representation in the Legislature would not be reduced and that state government would not interfere with the way they handled local affairs.

Moreover, voter restrictions had to apply to whites as well as blacks or the constitution would violate the 15th Amendment, which prohibited denying the right to vote on the basis of race. This did not bother many Bourbons, who were as fearful of the white-farmer vote as they were of the black.

The problem was that any new constitution would have to be approved by the voters, and it was unlikely that poor whites would vote to give up their vote. Somehow, white farmers had to be convinced that these restrictions would not apply to them.

As the pressure for a new constitution mounted, deals were made and compromises struck. White Alliancemen were told their vote would be protected. Black Belt leaders were assured that their position was secure.

Meanwhile, Bourbons in other sections of the state, especially the rapidly developing industrial region around Jefferson County, rallied to the cause. In November of 1900, the Legislature overwhelmingly called for a statewide vote to put the issue to the people.

On April 23, 1901, Alabamians voted 70,305 to 45,505 in favor of a convention to write a new constitution, and they selected delegates to do the job. Opposition came mostly from the hill counties of the north and the wiregrass region of the southeast ; Alliance strongholds where small farmers held sway.

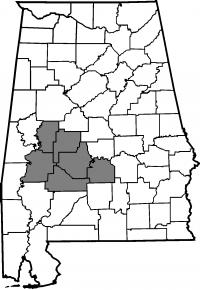

The Black Belt turned out in force for the Bourbon cause. Blacks voted, or were voted, in numbers that even caught the seasoned observers by surprise. In Lowndes County, where black voters held a 5 to 1 advantage over whites, 3,226 votes were cast for the convention and only 338 against it. In Dallas, Green, Perry, Hale, Sumter and Marengo counties, returns were much the same.

The convention met in May and went to work. Controlled by a coalition of Black Belt planters and industrial interests, it resolutely moved to guarantee suffrage to "the intelligent and the virtuous" voter and deny it to the rest. Residence restrictions, literacy requirements, the poll tax and property qualifications were written into the document, as were stipulations that potential voters had to be engaged in a lawful business and could not have been convicted of one of a long list of crimes, many of which (such as vagrancy) were frequently charged against blacks.

Poor whites who might have been disqualified were allowed to slip through if they or an ancestor had served in the military (the "grandfather clause") or, failing that, if they were of "good character" and understood "the duties of citizenship in a republican form of government"qualifications that black Alabamians at the whim of white election officials had little hope of meeting.

African-Americans were well aware of what was being done. Booker T. Washington led a group that petitioned the delegates for "some humble share" in choosing who would govern them. But the matter had been decided.

Black disfranchisement took up much of the convention’s time and was the subject of considerable debate, but it was not the only issue. Determined to preserve a status quo under which they had prospered, Bourbons refused to raise the tax ceiling to provide more funds for state and local governments and did not lift restrictions on state support for internal improvements. Counties could use local funds to build roads, bridges and public buildings, but limits placed on what they could borrow made such projects difficult to carry out.

Put simply, state and local governments would remain starved for revenue, and the services they provided, especially in education, would be underfunded for the foreseeable future.

Delegates also addressed what some observers called "the evils of local legislation." For some time, it had been recognized that the Legislature spent so much time on local bills that subjects of statewide interest were often neglected. The Mobile Register even went so far as to suggest that "it would be less expensive and far less dangerous to have each county of the state make the laws for its own government."

Since ratification of the constitution of 1875, the Legislature had enacted 20 times as many local as general laws. Because vote-swapping and backroom deals were the rule in passing local bills, some reformers considered this issue second in importance only to the question of suffrage.

But rather than grant the counties increased home rule, Bourbons kept local matters in the hands of the Legislature. It was a decision that would eventually lead to hundreds of amendments to the document they were writing and make Alabama’s constitution the longest in America.

Once written, it had to be ratified. Under the banner of "White Supremacy, Honest Elections and the New Constitution," the Democrats rallied their forces. Opposition came from those who saw that, in time, suffrage restrictions would be applied to poor whites as well as to blacks. But opponents seemed to know that no matter how many votes their side received, the Black Belt would deliver more.

They were right.

The constitution was ratified 108,613 to 81,734, a majority of 26,879. Outside the Black Belt, the constitution lost, but in the plantation counties, ratification got the votes to turn the tide.

In Dallas, Hale and Wilcox counties alone, 17,475 votes were cast for the constitution and only 508 against it; all the more remarkable because the total white-male voting population of these counties was 5,623.

The Bourbons stole the election and just about everyone knew it. But there was nothing the anti-ratificationists could do; no appeal they could make. The Bourbon Democrats had won, and in winning, they had created a system that would protect their power and prosperity.

Dallas, Hale and Wilcox counties in Alabama

As a leading historian recently noted, under this new government, "the rich, barring their own failure, would stay rich and the vast majority of poor Alabamians would stay poor," with little hope that a sympathetic state could help them in their plight.

The Bourbons had also written the most rigid constitution in Alabama’s history. Before the convention gathered, one state newspaper urged the delegates to draft a document with "room to grow in." They did just the opposite. What the delegates produced was more like a code of laws than a constitution, and the effect was to prevent change rather than promote it. But that was what the Bourbons wanted.

And so the constitution of 1901 became Alabama’s constitution.

It still is.

[source: Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform. (Harvey H. Jackson III is chairman of the Department of History at Jacksonville State University in Jacksonville, Alabama.)]

No comments:

Post a Comment