From the Hampton Roads Virginia-Pilot, "African-American voting power peaked in the 1860s," ny Bill Sizemore, on 6 May 2012 -- RICHMOND -- Later this year, if all goes according to plan, two plaques will be erected in the Capitol commemorating a little-remembered chapter of Virginia history.

The intent is to shed overdue light on a pivotal era in the Old Dominion's tortured dealings with the legacy of slavery.

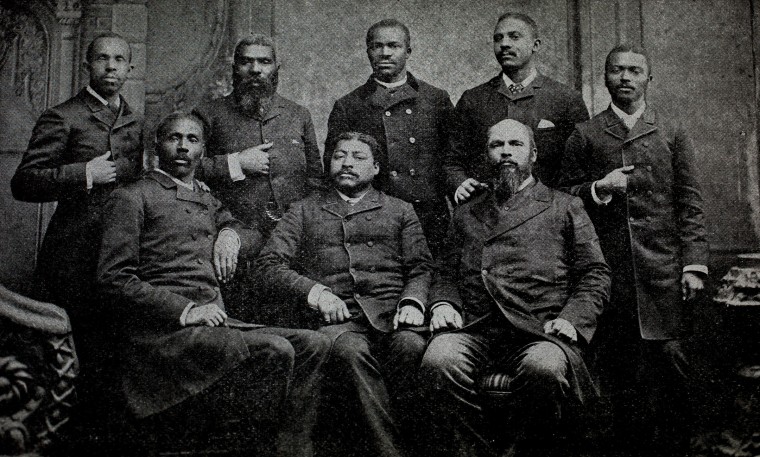

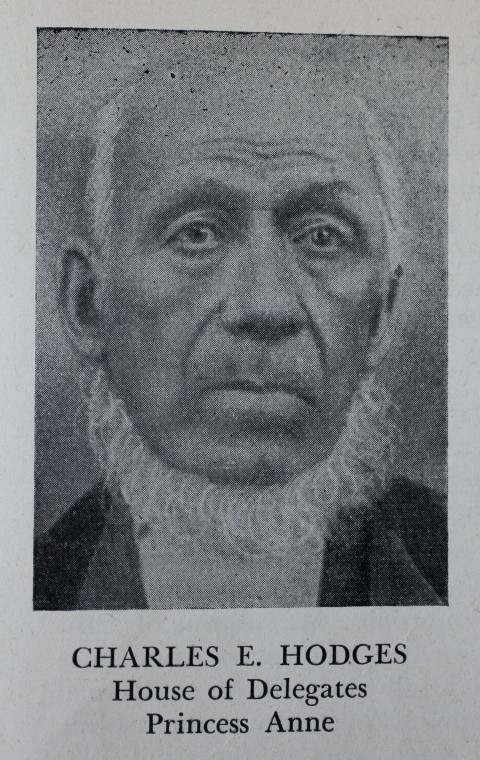

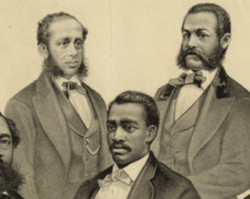

The commemorative plaques approved by the 2012 General Assembly will honor the more than 100 African American men elected to state office during Reconstruction, the brief window of political opportunity that opened for freed slaves for a few years after the Civil War.

The window soon slammed shut. The virulent racism of Jim Crow erased the freedmen's hard-won gains and reduced them and their descendants to second-class citizenship for nearly another century.

In the process - due in part, perhaps, to dismissive treatment at the hands of Southern white historians - those pioneering officeholders were largely forgotten.

Yet what they did was rise from the degradation of slavery in the face of implacable opposition from their former masters. Theirs is a story of indomitable grit.

Recognition of the Reconstruction-era African American officeholders was prompted by the coming 150th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln on Jan. 1, 1863.

In addition to the abolition of slavery, the end of the Civil War brought more life-altering changes for the freedmen.

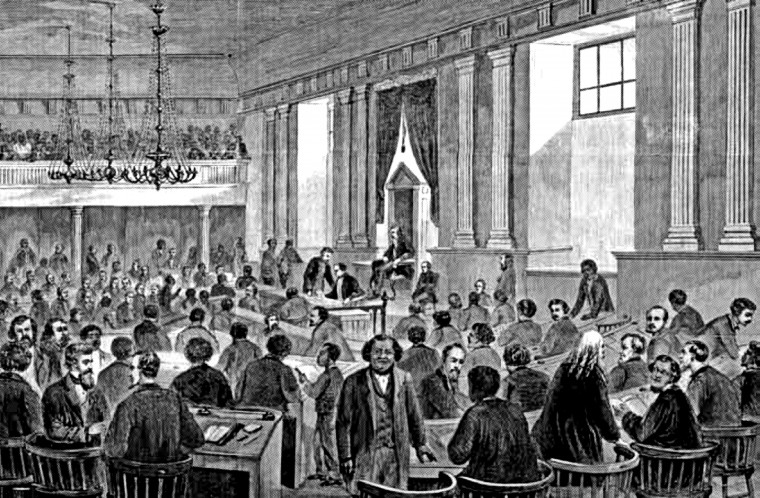

As a condition of readmission into the Union, former slave states were placed under martial law and required by Congress to hold state conventions and establish new constitutions. African American men were given the right to vote for delegates to those conventions.

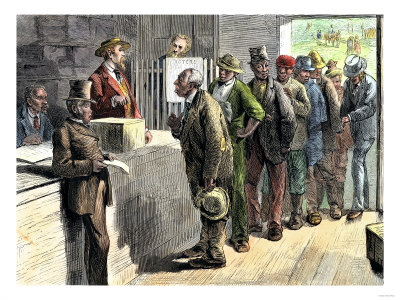

That taste of democracy stirred their souls. An account in the Norfolk Journal, describing the voting in Hampton, was typical:

"They commenced to assemble at an early hour in the morning, crowding the polls until their close at sunset. The best of feeling was manifested throughout the entire day, and the colored population seemed fully determined to enjoy to its fullest extent this, their first privilege of voting."

In Norfolk, Dr. Thomas Bayne, an ex-slave, minister and dentist, was the top vote-getter, finishing ahead of three white candidates. He was one of 24 African Americans among the 105 delegates elected to the 1867-68 Virginia convention that created the constitution of 1869.

A look at voter turnout in that 1867 election is illuminating. Statewide, 92 percent of registered African Americans voted, compared to 66 percent of whites.

"These people were not just sitting around and waiting for somebody to rescue them," said Cassandra Newby-Alexander, a history professor at Norfolk State University who has studied the period. "It shows what people will do when they feel an ownership of the political process."

The new constitution established universal male suffrage. One innovation enacted by the convention was the introduction of the secret ballot, replacing oral voting, to prevent unfriendly whites from retaliating against freedmen whose votes were not to their liking.

Education was another central concern of the convention, which established Virginia's first statewide system of public schools. Some delegates, led by Norfolk's Bayne, argued for racially integrated schools - a development that didn't occur for another century.

The first General Assembly elected under the new constitution assembled in Richmond in October 1869. Of the 199 members, 30 were African American. Over the next two decades, about 100 African Americans served in the legislature.

Viola Baskerville, a former member of the House of Delegates from Richmond who researched the era, said she was struck by the diversity of the African American lawmakers. There were 17 farmers, 16 ministers, nine shoemakers, eight teachers, six lawyers, three blacksmiths, two brickmasons and one boatman. One delegate, of Haitian descent, was bilingual.

Most were literate and owned property. Many were skilled tradesmen. One-third were born free.

"The other thing that struck me was how important education was to these people," Baskerville said. "There was a thirst for knowledge."

In 1882, led by an African American delegate from Petersburg, the Assembly created what became known as Virginia State University, the first fully state-supported, four-year institution of higher learning for blacks in America.

African American lawmakers introduced legislation to forbid discrimination in public transportation, protect tenants from abuse by landlords, ensure that blacks could serve on juries and punish the perpetrators of lynchings.

Such measures would merit an "of course" today. But the Reconstruction-era African American legislators and their white Radical Republican allies never won majority status in the Assembly, so many of their initiatives failed. One of their key objectives, abolition of the whipping post, was finally achieved in 1882.

The white-dominated Democratic Party exerted increasing control through the 1880s, and by 1890, there were no African Americans left in the Assembly.

In 1900, a convention was called to replace the 1869 constitution. There was no attempt to conceal its purpose: the effective disfranchisement of African American voters. The resulting constitution of 1902 restricted voting to males 21 and over who had paid a poll tax and owned property or could read and explain a section of the constitution.

Unlike the constitution of 1869, which was ratified by voters in a referendum, the new constitution was simply proclaimed the law of the state.

It had the desired effect. African American participation at the polls plummeted, not to be revived until the federal civil rights legislation of the 1960s. No more African Americans were elected to the Assembly until 1967.

Even today, African Americans have not regained the degree of representation they enjoyed at the peak of their power in 1869. In a 140-member legislature, there now are just 18.

"It shows how effective Jim Crow was," said Del. Jennifer McClellan, D-Richmond, the House sponsor of the commemorative legislation. "You had whole generations of people who were disenfranchised. It has been a very long and slow process for African Americans to regain the political power they had during Reconstruction.

"We've come a long way, but I think we still have a ways to go."

For many years, Southern whites' resentment over the Civil War and Reconstruction was reflected in their history books.

A striking example is "The Negro in Virginia Politics, 1865-1902," by Richard Lee Morton, a longtime chairman of the history department at the College of William and Mary. Morton Hall, an academic building on the Williamsburg campus, is named in his honor.

Originally published in 1918 as a doctoral dissertation, the book is shockingly racist by today's standards. It brands Reconstruction an "evil period" in which the freedmen were "but shortly removed from savagery and were utterly unfit for citizenship in a democracy."

The barriers to political participation raised by the 1902 constitution were a needed, if harsh, corrective, Morton wrote: "It is a matter of regret that it has been necessary to disfranchise a large body of citizens by methods some of which did not seem in themselves commendable," but they "threatened to corrupt the whole body politic of the Commonwealth."

Against the backdrop of such portrayals, it is time to shed new light on the era, said Baskerville, the former delegate.

"This whole period of Reconstruction has been misbranded," she said. "There was a vicious counter-response by people who had lived and thrived off a system of oppression, had benefited from it economically, and then saw the system change within the course of five years. They were bitter.

"This period was cast as a period of darkness when it actually was a Renaissance period in history."

No comments:

Post a Comment