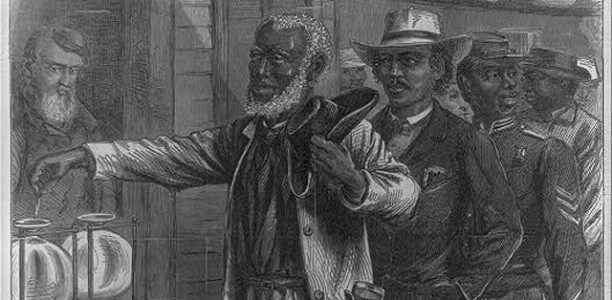

From the Tuscaloosan News "Professor examines black voting rights: Rob Riser's book delves into activism between 1890-1908," by Adam Jones, 31 May 2010 -- Black Southerners did not sit idly while leaders of the old Confederate states crafted ways to deny their voting rights near the beginning of the 20th century.

Indeed, 12 challenges came before the Supreme Court, all ending in crushing defeats. it is an era of civil rights activism often glossed over by historians who study the more organized and ultimately successful legal challenges decades later by the NAACP.

A new book by a University of West Alabama professor examines these early challenges that show not victims, but pioneers.

"They've been ignored because they lost, but you're ignoring an entire world of civil rights activism," Rob riser said. "I'm not saying it's a big world, and they failed. But the point is someone was attempting to fight at all."

Riser's book, "Defying Disfranchisement: Black Voting Rights Activism in the Jim Crow South, 1890-1908," was published by the LSU Press this month. While researching, Riser realized he was wading into deeper waters of history when he found one of the Supreme Court case files still bound in its original folder.

'I was the first person who had unwrapped it since it was put away nearly 100 years ago,' said Riser, also co-chair of UWA's department of history and social sciences.

The case is Giles v. Harris, decided by the nation's highest court in 1903. A challenge to voting requirements set in Alabama's Constitution, justices neutered black voting rights by refusing federal oversight of state election practices. It is a landmark decision, and one of the most ignored by constitutional and civil rights historians.

That no researcher ever opened the case to study its contents — the court's decision was widely available — represents, in a way, how historians treated the early efforts to overturn black disfranchisement.

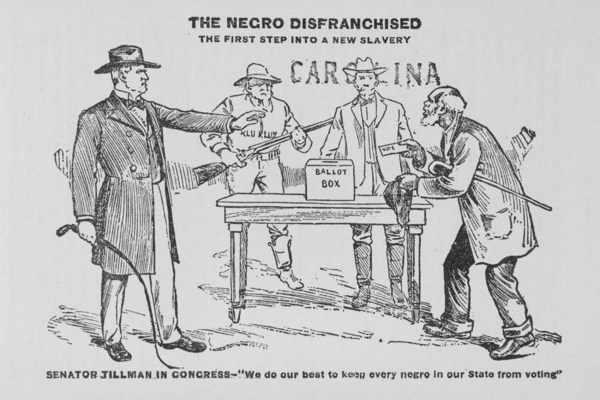

Beginning in Mississippi's new constitution in 1890 to Georgia's Constitution in 1908, Southern states began writing into law ways to deny blacks and, consequently, poor whites, the right to vote.

Initially caught off guard and, perhaps, believing Southern Democratic leaders that voting requirements such as literacy and citizenship understanding would be applied fairly, blacks never organized during the period. It wasn't until the NAACP formed in 1909 to challenge to disfranchisement and segregation systematically that civil rights activism could be called a movement, Riser writes.

'This disfranchisement came upon the negro like the shock of an earthquake. It came suddenly and violently,' said AME Bishop James Walker Hood in 1903. 'Some are only waiting to see how greatly they are damaged before making a move.'

In fact, Riser said those who brought early challenges — some financed secretly by Alabamian Booker T. Washington — believed the Constitution would put a stop to the eroding of their rights in state Capitols. After all, the 15th Amendment passed after the Civil War stated no one could be denied a vote based on race.

'They all believed they were going to walk into court, and the court was going to solve everything in one case,' Riser said. 'It became evident that it was going to take awhile.'

The court's decision in these cases made things worse for Southern blacks, but the early challenges brought attention to disfranchisement, defined the legal parameters and motivated a second and third generation of legal activists who had more success, Riser writes.

The most damaging of these early legal challenges was Giles v. Harris, and Riser devotes nearly half of his book to the case and Alabama's constitution.

Riser combs through stacks of newspapers from the day to show that Giles v. Harris was widely watched, regarded by some as the 'second Dredd Scott,' a reference to the famous 1857 case that ruled people of African descent could not become American citizens.

'It was front-page news,' Riser said. 'Nationwide, people are in a twist about this.'

The attention on the case stemmed partly from the attention two years earlier the nation gave to the Alabama constitutional convention, Riser said. In 1901, the framers of the state's constitution decided to publish a full record of their conversations and speeches after each day, published through a stunning technical achievement at the time the next morning in The Montgomery Advertiser.

The nation's newspaper chronicled Alabama's leaders as they set about to 'establish white supremacy in the state,' as delegate John Knox told the convention.

Also, Alabama's Constitution was the cleverest of the bunch, the framers having learned from their peers in Mississippi, Louisiana and South Carolina on how to sidestep the federal Constitution, Riser said.

'Alabama's Constitution of 1901 is the high watermark of disfranchisement,' he said.

In 1902, Jackson Giles, president of the Colored Men's Suffrage Association of Montgomery, filed a petition in federal court to force the state to register him and 5,000 other black men. The federal district court refused to hear the petition, which was rushed to the Supreme Court.

At its heart, the justices had before them a question of whether the district court could hear the petition, and the Supreme Court said in a 6-3 decision that the federal court could not get involved in addressing political rights, essentially throwing the responsibility to Congress.

Also, Giles claimed Alabama's entire voter registration process was a fraud, so if the justices forced registration, they would be a part of the fraud, wrote Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes for the majority.

'It was the death nail to the Constitutional challenges of disfranchisement,' said Richard Pildes, a New York University law professor who began to bring attention to Giles' case in a paper published in 2000. 'Giles was the case in which the Supreme Court said we are not going to get involved in this.'

Practically, Holmes was bowing to the political realities of the day, Pildes wrote without condoning his choice to not rule on the matter. The thought of the Supreme Court enforcing its order and ensuring registration of blacks throughout the south was unthinkable in 1903.

Congress had also refused to seat representatives from the South thought to be elected undemocratically during and after Reconstruction, but that practice stopped after the Giles case, Pildes writes.

Riser writes that Giles v. Harris along with Plessy v. Ferguson, which ruled separate but equal segregation Constitutional, are the two pillars the Jim Crow South stood on. But, unlike Plessy, mentioned in most any American history book, Giles was ignored.

Its snubbing by constitutional scholars and historians probably comes because justices didn't address the merits of the case officially and it was dismissed on a technicality, Pildes said.

Still, it was cited in a 1947 Supreme Court decision refusing the federal government's oversight of election apportionment, and wasn't overturned until the famous Baker v. Carr in 1962, which established the one-man, one-vote principal of district size. In that case, justices did involve themselves in a political question. Lastly, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 officially flushed the precedent of Giles.

Pildes said he is hopeful Riser's book can bring more attention to the role Giles v. Harris played in constitutional law, and Riser hopes more will appreciate the early efforts of Giles and his contemporaries.

'Somebody had to be the first to do this,' Riser said. 'It's all to the good they made the fight.' (source: Tuscaloosan News)

No comments:

Post a Comment