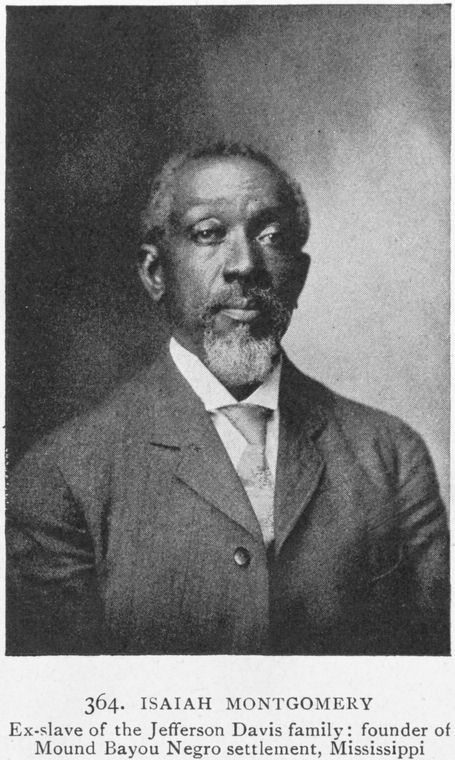

Isaiah Montgomery, former slave of the Confederate President Jefferson Davis and founder of the Mound Bayou Negro settlement in Mississippi.

From the JRank Encyclopedia -- Isaiah T. Montgomery was active in local and state politics. A Republican, he was the only black delegate elected to the Mississippi constitutional convention in 1890. Montgomery and his family had for a long time become skilled in pleasing whites and in receiving their patronage. He believed, however, that blacks needed a segregated colony where they could promote their own interest. It was at that convention that efforts to disenfranchise blacks were put in motion. While Montgomery had the confidence of many whites, clearly he was acquainted with the racial climate in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Mississippi. Since he was a man with accommodationist sympathies and beliefs, he saw nothing wrong in delivering an hour-long speech in which he conceded that it would be in the best interests of both races to reduce black vote to a total far less than that of whites. He saw nothing wrong with disenfranchising 123,000 blacks and some 12,000 whites. This would help race relations, he thought, and blacks would have to increase their education and acquire property, then reenter politics themselves. The amendment also imposed a poll tax as a requirement to vote and exclude those who were illiterate or who were convicted of certain crimes. Montgomery’s action brought mixed reaction from black leaders: Abolitionist Frederick Douglass thought that he had been tricked into taking such a stance; New York lawyer T. McCants Stewart called his advocacy a move to enfranchise illiterate whites and disfranchise illiterate blacks; and Mississippi Republican John R. Lynch called his action more dishonest than the practice of stuffing ballot boxes, which Mississippi knew well.

The state adopted the amendment, and by 1915 other former Confederate states followed. Within a twenty-year period after the convention, Montgomery admitted that all was not well in his state. Hermann quotes his prediction that “the dominant spirit of the south will be satisfied with nothing less than a retrogression of the Negro back towards serfdom and slavery.” And clearly, by 1904, he admitted to the work of whites who terrorized and intimidate black Mississippians.

Montgomery resigned as mayor of Mound Bayou in 1902 when, on endorsement from Booker T. Washington, President Theodore Roosevelt, who forgave him for his political transgression, appointed him as receiver of public funds in Jackson, Mississippi. Sometime in 1903, he was accused of placing $5,000 of government money into his own account. He met secretly with Washington’s secretary in New Orleans in 1903, who told him that he must resign his post. Montgomery stayed in office a few months longer, then resigned and returned to Mound Bayou. He had been reluctant to accept the post in the first place, but deferred to the wishes of his friend Washington. His primary concern had been for the development of his colony, Mound Bayou, and he had considered Washington his connection to northern white philanthropy to fund more ambitious projects and businesses there. He also faced hostility from his white staff in Jackson. Continuing in politics, however, in 1904 he was Mississippi delegate to the Republican National Convention.

Isaiah and Martha Robb Montgomery, who married in 1871, had twelve children, eight of whom reached adulthood. One daughter, Mary Booze, became a committee-woman for the national Republican Party. Martha Montgomery, who had become an important business partner, died in 1923, seven months before Montgomery’s death in Mound Bayou on March 6, 1924. The Montgomerys’ residence is listed on the National Register of Historic Places; it is one of the nation’s most historic black culture sites.

To his credit, Montgomery had been involved in nearly every project of interest to the Mound Bayou area; he also worked diligently to promote black self-sufficiency and to enhance the quality of life, especially for those blacks who lived in Mound Bayou. But, as Hermann wrote, Montgomery finally admitted that he could not forgive himself for standing by, “consenting and assisting in striking down the rights and liberties of 123,000 freedmen.” [Read more: Endorses the Disenfranchisement of Blacks - Montgomery, Mississippi, Mound, and Whites - JRank Articles http://encyclopedia.jrank.org/articles/pages/4383/Endorses-the-Disenfranchisement-of-Blacks.html#ixzz264XXjLZy]

No comments:

Post a Comment