An article from the Intelligencer, Wheeling News-Register entitled, "Slavery Alive And Well in Wheeling," on 4 March 2012, by Margaret Brennan -- Even as the observance of Black History Month has concluded for another year, it might be well to focus on slavery and the Civil War era, especially as it relates to Wheeling.

In March of 1861, Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, pointed out, "... our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us ... was the immediate cause of the late rupture." Bob Sutton, chief historian for the National Park Service, stated: "Slavery was the principal cause of the Civil War, period." There were other important and contributing issues, but slavery was at the core of the rending of the Union.

Some of the founding fathers and mothers of Wheeling were enslaved, as we know the history of Ebenezer Zane's slave, "Daddy Sam," and "Aunt Rachel," another Zane slave who lived to be over 100 years old. The Zane wills are chilling as they bequeath slaves as they do their household goods.

Probably the largest number of enslaved belonged to Lydia S. Cruger who, in the 1850 census, owned 13 slaves, including Israel, Jack, Susan and Mandy, a 5-year-old.

Wheeling as we know it during the Civil War was divided in its loyalties. The upper class gentry often had feeling for "old Virginia." Thus, we see names such as Zane, Hughes, Moore, Goshorn, Steenrod and Phillips on the "traitors" list. Often these families owned slaves, usually domestic servants that tended the house, helped rear the children, did the cooking and drove the carriage. There is evidence today of this life in the slave galleries of two local churches, First Presbyterian on Chapline Street and old St. Matthew's Episcopal, now the Church of God and Saints of Christ, on Byron Street. There the slave benches, set against the gallery back wall so as not to be seen from the main body, put us in touch with those tragic times.

In 1860, the population of Wheeling was 14,100 and the slave population of Ohio County, with no separation for Wheeling, was 100, with 42 males and 58 females. There were also free black males and females among the citizens.

Wheeling was part of the social and political fabric of slaveholding Virginia. Knowing this and the city's key location in terms of the National Road and the Ohio River, it is not unexpected that there would be a flourishing slave auction block here, located at the north end of the Second Ward market house at 10th Street.

Corn crib in Negro coal miner's backyard, Bertha Hill, Scotts Run, West Virginia

Thomas B. Seabright, in his history of the National Road, wrote: "Negro slaves were frequently seen on the National Road. They were driven over the road arranged in couples and fashioned to a long, thick rope, or cable, like horses."

Joseph Bell, born in 1819, remembered seeing on Wheeling streets, "gangs of slaves chained together, women as well as men, on their way south. As a little boy, I remember standing on the sidewalk with my brother when such a gang was passing. We were eating an ear of corn apiece, which some of the slaves begged from us."

The market bell would ring, announcing the slave auction. It is vividly described in the book, "Bonnie Belmont," by Judge John Cochran. In 1855, he wrote, "it was a wooden movable platform about two and a half feet high and six feet square, approached by some three or four steps. The auctioneer was a little dapper fellow with a ringing voice. Not a very large crowd was surrounding the auction block. On top of it was a portly and rather aged negress and the auctioneer."

In December 1858, the Wheeling newspaper reported: "Five negro girls ... were sold last week for one thousand dollars each." Many of the slaves auctioned at Wheeling were bought by agents for plantations in the deep south and as they say were "sold down river" for back-breaking work in the cotton fields. Others might find themselves in the Kanawha Salines near Charleston, at its peak employing 3,140 slaves to extract the pure red salt.

One of the more well known slave stories of Wheeling concerned Sara Lucy Bagby. She was purchased by John Goshorn for $600 in January 1852 in Richmond, Va., and in 1857 she was given to John's son, William. In 1860, Lucy escaped to Cleveland, where she became a maid at the home of A.G. Riddle, a congressman-elect. It became politically expedient for him to send Lucy to work for a jeweler friend, L.A. Benton.

Apparently someone in Cleveland alerted William Goshorn to Lucy's whereabouts and he traveled to the city where he contacted the U.S. marshal, demanding her return. The marshal took Lucy into custody and at her hearing the next day, Jan. 20, 1861, large crowds gathered. Lucy's case was postponed for two days while evidence was gathered and she was held in the post office building, a twin to West Virginia Independence Hall.

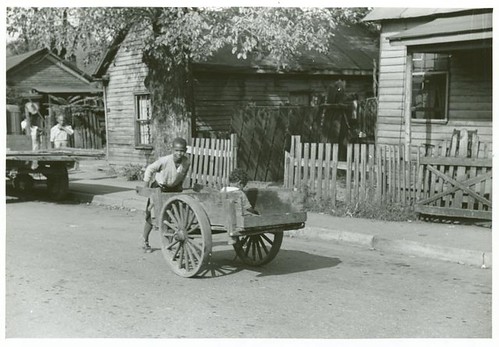

Negro housing in West Virginia

It was proven she was indeed the property of William Goshorn, so under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, she had to be returned to Wheeling and her owner. The people of Cleveland had raised almost $1,200 to buy her freedom, but Mr. Goshorn would not hear of it.

Getting Lucy Bagby out of Cleveland was no small feat as many wanted her rescued, even by force. The sheriff swore in 150 new deputies who escorted Lucy and her owner to the train where she was returned safely to Wheeling, only to be placed in jail. After a few days, she was sent to Charleston to stay with Goshorn relatives until things quieted down.

Lucy was eventually freed and went to Pittsburgh where she married George Johnson, a former soldier in the Union Army. She and her husband relocated to Cleveland where Lucy worked as a cook and house servant for the leading families. It is said she came back to Wheeling to visit William Goshorn before he died in 1891.

Negro homes in Charleston, West Virginia

Lucy, formally Lucinda, died of septicemia on July 14, 1906, at about 63 years. She is buried in Woodland Cemetery in Cleveland and had an unmarked grave until recently when a benefactor donated a gravestone. Lucy is considered the last fugitive slave returned under the 1850 law.

Outhouse used by Negroes living in shacks on highway between Charleston and Gaauley Bridge, West Virginia.

As Abraham Lincoln noted in 1864: "If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong." Sara Lucinda Bagby Johnson and her fellow enslaved in Wheeling and elsewhere testify to this truth. (source: Sunday News-Register , The Intelligencer / Wheeling News-Register)

Homes of Negroes in "Paradise Alley," Charleston, West Virginia

On October 11, 2011, Dr. Philip Sturm presented "Slavery in the Ohio and Kanawha River Valleys: Using Local Primary Sources to Uncover the Past" at the Tuesday evening lecture in the Archives and History Library. He used primary sources, including wills and census records, to present a more accurate picture of slavery in western Virginia.

No comments:

Post a Comment