The Civil War unleashed a revolution that left few areas of national life untouched. Liberation transformed what had been the largest portion of the nation's antebellum labor force - slaves - into wage workers, and planters entered into contractual relations with those they had owned, promising however grudgingly to pay for labor services they had customarily taken by force. Individual citizens found themselves in new relationships with the state, the result of four years of war during which the national government inserted itself in new ways into areas that had once been the purview of individual states: assessing taxes, conscripting soldiers, and later, offering aid to veteran soldiers and to tens of thousands who had been displaced and impoverished by war. Political parties realigned and the Republicans, who in the 1850s had been mostly confined to eastern and northern states, swept into and across the former Confederacy, transforming the political landscape.

The revolution did not stop there. As is the case with most major conflicts, the Civil War and emancipation wrecked havoc on existing gender relations, propelling women and men into unaccustomed roles and in the process, forcing Americans - black and white, rich and poor, propertied and not - to reconsider what it meant to be a good woman, a good man, a good partner, a good parent. In the Confederacy, for example, the departure of white men to the front lines pushed white women into areas formerly reserved for men: tending crops, overseeing enslaved field hands, offering up

For example: military service, and the assumptions about manhood it gave rise to, provided black men with a compelling argument for the exercise of full citizenship rights. In their minds, and in the minds of most nineteenth-century Americans, they had earned that right on the battlefield.

At the same time, white conservatives, made anxious by the rising power of black men - at the bargaining table, at the voting booth, and eventually in elected office - regularly attempted to paint their opponents as female, a rhetorical strategy meant to call into question freedmen's capacity for independent political action. Women, such proponents would argue, were "naturally" dependent and for that reason "naturally" unfit for civic and political duty. Thus "gender" and the countless discussions about what it ought to mean, for whom, and why, took shape from and gave shape to nearly every aspect of social, civic, and productive life in the post-Civil War nation. The documents presented below are meant to provide a small taste of a dimension of human experience that was at one and the same time a product and a producer of new power relations.

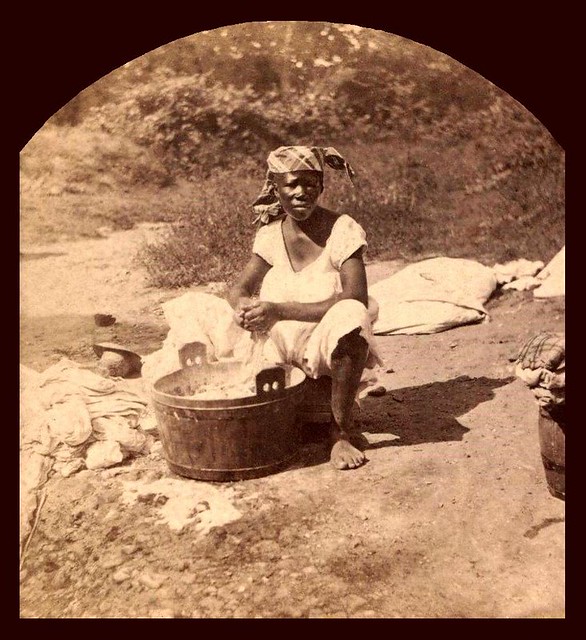

Sabbath-day sermons, and engaging in public and paid labor. Some enjoyed the opportunities opened by war. Others were horrified, wishing for nothing more than a return to antebellum conditions, especially as their enslaved servants laid down their tools, dropped their dish rags, and abandoned the wash tubs that stood in every yard - actions that compelled more than a few prideful white women to perform chores they still considered the work of slaves.

War and emancipation transformed the gendered lives and ideals of black Americans too. Enlistment in Lincoln's armies, for instance, changed fundamentally the ways black men thought about themselves in relation to their wives, their children, their states, and the nation. Introduced to Northern gender sensibilities as they marched alongside and fought alongside Yankee soldiers, black Southerners who served often returned home with new understandings about what it meant to be men. As new scholarship has revealed, the enlistment of men also changed how black women thought about themselves and about their social, civil, and political rights. Many, for example, believed that the sacrifice of a son or husband on a faraway battlefield bought them the right to intervene directly in political matters. For the enslaved left behind on Confederate plantations, the departure of men forced them to reconfigure themselves into wholly new domestic units, drawing together the female, the aged, the infirm, and the young in "families" of people who may or may not have been actual kin.

Gendered ideas, expectations, and experiences continued to evolve beyond the end of the war. As the documents assembled below suggest, the tumultuous circumstances of freedom rendered "gender" - those understandings about what it meant to be good women and good men - a particularly volatile set of ideas. The advent of wage labor proved especially treacherous for black women. Once prized by slaveholders for the babies they could bear, freedwomen found themselves shunted swiftly to the side, roughly dismissed by planters who could not afford - and with emancipation, no longer needed - women who could bear babies. As one Union official observed from his post in Alabama, such women along with any young children were soon "every where regarded and treated as an incubus." Yet that same devaluation of black women as agricultural wage workers thrust black men into new roles. For in seeking to survive a freedom that had turned suddenly bad, black women turned to those they knew the best for assistance: calling on their husbands, sons, and brothers to represent women's interests in a capricious and gendered labor market.

As gendered ideals and assumptions continued to evolve, shaped this time by the deeply contingent circumstances of emancipation and free labor, they were often caught up and deployed in political debate. Frequently considered one of the most "natural" of divisions, though always and everywhere the product of human creation, gender and the languages to which those ideas give rise, became commonplace weapons as black people and white jockeyed for power.

Document 1:

The Social and Domestic Price of Free Labor

The end of 1865 brought with it the end of contracts that for the most part recast entire former slave labor forces as wage workers. In turn, the termination of that first round of labor agreements brought with it the requirement that planters pay their former slaves for services rendered. It was a revelation that compelled ex-slaveholders and Southern employers to quickly reconfigure their work forces. The most profitable workers, the workers they were most willing to pay wages to, were those they considered the best workers. It was a new expectation that put privileged former slaves who could split three hundred or more fence rails in a single day, lift 500-pound bales of cotton on and off wagons, and manipulate the heavy cast-iron ploughs that farmers routinely used for opening up new fields and preparing old ones for a season's crops. Thus as planters began to recruit workers for the 1866 season, they applied a new calculus-one born out of the new circumstances of freedom, and one, more over, that tended to favor black men.

For example: military service, and the assumptions about manhood it gave rise to, provided black men with a compelling argument for the exercise of full citizenship rights. In their minds, and in the minds of most nineteenth-century Americans, they had earned that right on the battlefield.

At the same time, white conservatives, made anxious by the rising power of black men - at the bargaining table, at the voting booth, and eventually in elected office - regularly attempted to paint their opponents as female, a rhetorical strategy meant to call into question freedmen's capacity for independent political action. Women, such proponents would argue, were "naturally" dependent and for that reason "naturally" unfit for civic and political duty. Thus "gender" and the countless discussions about what it ought to mean, for whom, and why, took shape from and gave shape to nearly every aspect of social, civic, and productive life in the post-Civil War nation. The documents presented below are meant to provide a small taste of a dimension of human experience that was at one and the same time a product and a producer of new power relations.

The end of 1865 brought with it the end of contracts that for the most part recast entire former slave labor forces as wage workers. In turn, the termination of that first round of labor agreements brought with it the requirement that planters pay their former slaves for services rendered. It was a revelation that compelled ex-slaveholders and Southern employers to quickly reconfigure their work forces. The most profitable workers, the workers they were most willing to pay wages to, were those they considered the best workers. It was a new expectation that put privileged former slaves who could split three hundred or more fence rails in a single day, lift 500-pound bales of cotton on and off wagons, and manipulate the heavy cast-iron ploughs that farmers routinely used for opening up new fields and preparing old ones for a season's crops. Thus as planters began to recruit workers for the 1866 season, they applied a new calculus-one born out of the new circumstances of freedom, and one, more over, that tended to favor black men. (source: http://153.9.241.55/atlanticworld/afterslavery/chapter7.html)

In the report published below, a Freedmen's Bureau agent from Georgia's eastern cotton belt reflects on the unexpected price planters' new expectations levied against those who could not work like able-bodied men.

Eatonton Putnam Co. Ga. 25th Dec. 1865.

Sir Such a variety of cases amongst the freedmen arises that I must trouble you for instructions in regard to these at least. a part of such as have been presented and to ask for general instructions in relation to such cases as may yet arise for which no provision is made.

Some men have abandoned their old wives by whom they have several children and taken new wives and are trying to get possession of the older children who are able to assist the mother leaving the helpless ones to the mother. in such cases it is impossible for the mother to find employment which will afford subsistence There are many women whose husbands left last N[ov]. 12. months with the army of Gen. Sherman leaving the mothers with several small children, then there are many helpless and decrepid men and women whose children cannot take care of them Now where are those to be sent[?] and by what means? there are no Hospitals or Assylums here. Believing that human sagacity can not foresee all the cases that may arise out of this new state of things is the reason that general instructions and powers is asked for. In all cases not perfectly clear. It is preferred that the Agent call to his aid two intelligent men. Respectfully

[signed] Wm B Carter

Source: Wm. B. Carter to [Gen. Davis Tillson], 25 Dec. 1865, Unregistered Letters Received, ser. 632, GA Asst. Comr., RG 105.

"Disappeared... Enslaved Women and the Armies of the Civil War"

No comments:

Post a Comment