"From the blood of kings to Lincoln County slavehood; local man bought slaves off ship in Charleston," From an unedited article reprinted in the Louisiana Historical Quarterly in 1919: by F. Brevard McDowell

A letter written in the early part of the first decade of the last century by Judge Joseph Brevard, of Camden, S. C., to his brother, Captain Alex Brevard, owner of Mt. Tirzah forge, in Lincoln county, N. C., conveyed the information of the expected arrival in Charleston of a trading vessel freighted with African slaves. Acting upon that intelligence, and with a view of enlarging their iron industry, Colonel Ephraim Brevard, son and partner of Captain Alex Brevard, proceeded to Charleston on horseback, with a wagon following him. At that time there were no railroads; and vehicles and horses were the only modes of transportation. Judge and Captain Brevard had both been officers in the Revolutionary war, and the iron works of Lincoln county, conducted by the Brevards, Grahams and Forneys, were the only enterprises of that character south of the Tredegar Works in Richmond.

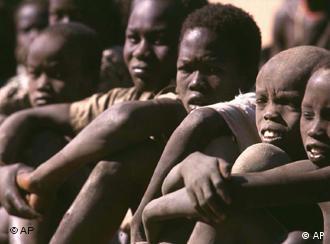

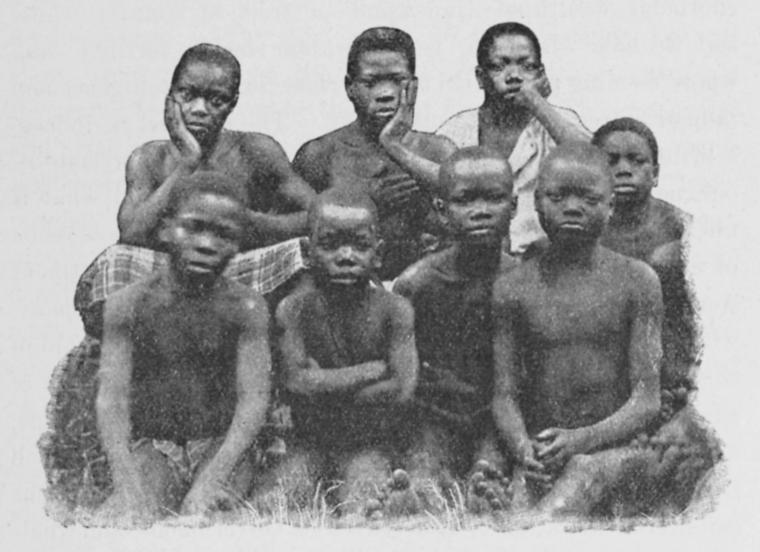

Upon the arrival of the ship in Charleston , Colonel Brevard bought a wagon load of African boys, of varying ages and sizes, and one man. For some reason he purchased no females; probably there was none upon the market. He paid a fictitious price for the negro man who, though densely ignorant and absurdly superstitious, was active and sprightly. He was reputed to be the son of an African King.

After the boys were decently clothed and properly fed, and the wagon was loaded with the young Africans and a quantity of ginger cakes and some other provisions, the start was made for North Carolina. There was no mishap until the attempt was made to ford a certain stream, which was much swollen. The waters swept the provisions from the wagon, and the boys who had a taste of the ginger bread, seeing their favorite viand disappear, leaped as one person in pursuit. Several of the boys were carried by the current a hundred yards or more below the crossing, and the others were rescued from drowning with the utmost difficulty. One when taken out was unconscious, with a mass of ginger cake clutched in his hands.

When they arrived and were domiciled at their future home the new negroes early exhibited a keen relish for young pigs, which they easily caught and greedily devoured, without the formality of cleaning, cooking or serving; for from their earliest recollections, nature had been their cook and necessity their caterer. They had to be punished repeatedly before the pigs of the plantation had any security from molestation and killing.

At first the boys broke and destroyed the plates upon which their meals were served. Oblong wooden trenchers were then substituted for the plates, but they continued to fight like animals over the food. After the necessary training and corrections, they progressed sufficiently in table manners to eat from tin platters, sop pot-liquor with bread, and finally to use knife and fork.

The negro man, on account of his consequence and supposed kingly blood, was designated by the royal name of Caesar; Cicero and Pompey, though younger, enjoyed the same distinction; the other boys were given less conspicuous Roman or classic appellations. While most of these negroes had a tendency to pilfer gaudy articles, and take tempting eatables, the theft of valuables was exceedingly rare. Only one of the number as they grew to manhood, turned out badly — Scipio, who was fearless, defiant and possessed of a high order of cunning. He robbed the Brevard residence of considerable jewelry and silverware, and Major Robert Brevard’s private office of $600 in money. It required months of the cleverest detective work to recover any of the missing property and locate the criminal. Being regarded as a dangerous character he was sold and sent to a distant State. Nothing could induce him to divulge the name of the accomplice, declaring he would prefer death to betrayal. When on the eve of leaving, however, he confided to the overseer that his confederate was a white man, who stood guard at the window while the house was being ransacked.

According to popular superstition, “White in the eyes” was regarded as an infallible sign of trickery in both man and beast, and it boded no good to the possessor. So after Scipio’s banishment and disgrace, wise-acres boasted that they had always predicted such an end, from his eyes.

Pompey and Hannibal became expert moulders, and both were valuable in mechanical and constructive work. Pompey was full of good humored wit, and was an entertaining talker. When the native darkies jested their African brothers about their comparative nudity at the landing in Charleston, Pompey cleverly turned the laugh by declaring that he was in swimming when caught. He boasted that he had a trunk full of good clothes at home which his captors would not permit him to bring, but that his fellow captives never did possess any other garments than those worn by the monkeys.

He developed such aptitude as a manager, that Captain Alexander Brevard, now living at the old homestead in Lincoln county, sent him to Texas, where he became herdsman of a large number of cattle, and was more than content with his little kingdom on the plains.

Cicero was promoted to be the founder or superintendent of the furnace. Considering his opportunities, he was a more than ordinary man; and in point of intelligence and practical sense was far in the lead of his associates. He had a large force of workmen under him, whom he managed with admirable skill and judgment. When an underling was caught nodding or napping over his task, Cicero would drench him suddenly with a bucket of cold water; and that was about as harsh a reprimand as he usually deemed necessary. Polydore had the responsible position of keeper of the furnace under his direction.

Brutus was irascible, quarrelsome and despised by his co-workers. Though small in size he was a splendid teamster, and had control of the horses and oxen. He was a tyrant in his dominion, and allowed no interference in his mode of animal government.

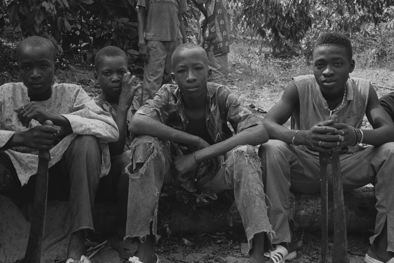

General Joseph Graham purchased several of the African boys shortly after their arrival in Lincoln county. They were trained to assist in his iron works situated a few miles distant and proved to be intelligent and desirable laborers.

At the death of Colonel Ephraim Brevard, and by the provisions of the will, my mother, who was a niece, received three of these Africans; Caesar, Nero and Cato were their names, and I remember them perfectly. My earliest recollection is of Caesar, a small white-haired, white-bearded, chair-ridden old man, cross, petulant, garrulous. He always had a crutch by him, which aside from its legitimate use, he often employed in cracking the heads and shins of little pickaninnies whenever the temper seized him; and he chuckled with infinite glee over their cries of pain and exhibitions of impotent rage.

For a long time chickens mysteriously disappeared. The smell of burning feathers was traced to Caesar’s cabin, and a watch was placed upon it. He was detected in decoying the fowls with bread-crumbs, knocking them over with his crutch, hiding them under a plank in the floor, and adroitly waiting till night for the cooking, so as not to betray himself. His face was very wrinkled, features drawn, and it was reported that he was more than 100 years old, but that was a matter of conjecture.

When in a pleasant mood, Caesar delighted to relate his experiences in the old country, across the great waters; but his narratives were not reasonable or trustworthy. His effort was more for effect, and to excite the admiration and wonderment of his hearers by his incredible fictions. His pictures were nearly always on the marvellous and fantastic order. One Sunday, he told a crowd of eager listening native negroes, that once he came, while in Africa, of a river two miles wide and a mile deep; it puzzled him to know how to cross it; then he placed each big toe in an immense egg-shell and floated across. There was no sense in such a story, and the act was impossible but the shout of laughter and approval that went up from the simple minded auditors completely broke up the solemn stillness on that Sabbath-observing old plantation. The native negroes regarded one born across the sea with an awe akin to that inspired by a supernatural being, and old Caesar’s extravagant tales were a source of intense pleasure and entertainment to those who had known and heard but little beyond the scenes and enactments of a monotonous neighborhood.

When I first remember Nero and Cato, they were both of advanced age and I was constantly thrown with them. Nero had been sent to Camden, S. C. where he learned the trade of carpenter. We had frequent commercial transactions around the work-bench. He would make for me toys and cross-bows; and I, in turn would surreptitiously abstract plug-tobacco and an occasional dram for him from “the big house,” as he admiringly termed my father’s dwelling. When angered his words could not be understood at all, and at these times the native negroes declared that he was “a Guinea nigger and a ban man,” and would flee

in terror from his presence. He made a practice when in a rage, of hurling the implements of his trade at their retreating forms. They had some reason for fear.

Cato was the reverse of Nero in temperament. There was no foreign accent in his language. He was mild mannered, amiable, and kind, and very religious. His duties consisted in shearing sheep, tending horses and going upon important errands to stores and the towns. He had a short thick-set body, and large benignant features. Nero was spare made, coal-black, low of stature, austere, and forbidding in manner. Both had a distinctive air of almost patrician dignity. They were generally closely shaved and neat in appearance, whether working in their shirt sleeves or walking around in Sunday costume. Each wore small side whiskers in imitation of the English style in vogue among the prominent planters of the day. They came from different sections of Africa and belonged to different tribes.

Cynthia, Nero’s daughter, was my nurse, and this circumstance recalls many pleasant childhood memories. She taught me the lore of Bre’r Rabbit and the Tar Baby long before it appeared from the pen of Joel Chandler Harris. Where she learned the stories is not known. She loved nature and nature’s creatures, and talked to the domestic animals as if they could understand and answer. She was fond of fishing for minnows in the brooks but few things pleased her so much as taking one dinner along in a bucket and going with children to spend the day in the midst of the primeval forest, where she would seem happily to commune with the wilderness, the birds and the trees. She often took me to the spot where she said she found me as a baby. It was a hollow stump. She heard me crying, a poor wee thing, and a hawk was trying to carry me off. I was mad and red in the face from fighting the hawk. At every such recital, she would sit down and laugh immoderately. As my youthful philosophy could not solve the riddle of how I came there, I was stung by the ridicule and awkwardness of the situation and thought it unkind of her to refer to the occasion so often; but at no other time was she disagreeable, for she was as companionable as a child; less combative and more sympathetic.

Caesar left a descendant, who was cross-grained, contentious and liked by no one. His face in repose had a striking suggestion in it of nagging pain and sullen discontent; when excited by disagreeable events, his coarse broad features seemed animated by conflicting emotions of fierce passions and intense hatred, while his voice under such circumstances had a grating metallic, hissing sound.

Caring nothing for human companionship, he had but few friends. With dog and axe, he would scour the woods in season for opossums. He loved the sport. He was also a tireless worker, and on moonlight nights, he would gather cotton alone in the fields in order to gain the money prize offered for the best cotton picker on the plantation.

Between this fellow and a certain woman, a cross between Indian and negro, there had long been an implacable feud, which had culminated in a conflict, from which the man emerged with an ugly knife scar upon his face, that marked him for life. About the year 1860, the woman died, and there was a largely attended funeral. After the body was lowered and the grave filled, the elderly man prayed in exhortations that evoked the wildest wailings and lamentations. The emotions and sobbings of the women became infectious, and rendered the scene inexpressibly weird and solemn. Caesar’s son stood aside from the crowd of mourners, taking no part in the ceremonies, exhibiting no interest, expressing no sympathy. As attempts to shame him into action were futile, he was loudly importuned to say some words of commendation and forgiveness for the deceased. He accepted the challenge, and mounting the newly made mound, like a game chicken standing upon the prostrate form of his antagonist, he said in measured, defiant tones, that he didn’t want to speak, but had been forced to — and would tell the truth if he was struck dead for so doing. They all knew God had no use for sinful people, and He sent them to the devil. They couldn’t deny, he said, that the deceased had always been bad and wicked. It did no good to pray after people were dead. It grieved him to say that the departed sister was in hell, but as there was no way to get her out, she had to suffer and burn forever for her sins. God was good, just and truthful, and he dared them to deny it.

The surprised auditors seemed spell-bound during the utterance of such shocking inhuman sentiments, and at the conclusion in a threatening manner surged madly to revenge the memory of the dead, and do bodily harm to the unnatural accuser, but he cursed them, and arming himself with rocks from the graveyard wall, he warned them not to follow. He then walked slowly down the road, muttering aloud a life-long conviction that the world had a “pick” at him, and that he was always censured for quarrels he never provoked.

Descendants of Nero and Cato are scattered abroad over a number of States, and those living in and around Charlotte compare favorably with the best of their race. One of Nero’s grandsons, a type of his progeny, has been employed in a responsible position, by a wholesale grocery firm of Charlotte for nearly twenty years, a testimonial to his honesty and efficiency.

At a recent election his vote was challenged on the ground that he lived in one city ward and his wife in another; whereas, the law prescribed that the voter’s polling place should be where a voter’s wife resided. He thought it a hardship and an injustice; and in speaking of the separation that had taken place between them said it was by mutual consent. “Me and her,” he continued, “agreed, and there was no quarrel or hard feelings about it. She acted a perfect lady throughout. I told her I wanted to marry another woman. She said she would consent, if I would let her marry the man she wanted. I said it was a trader and we both agreed and lived apart. We have no children; it hurts no one; it’s nobody’s business, and it isn’t right for people and the law to concern themselves about us.”

He had been of opinion that divorce laws were only conventions between couples that could not amicably agree to a severance of the marriage ties, not otherwise. Such was the logic of his mind and the mode of reasoning the moral phase of the question he was utterly unable to comprehend. Sifted down, he was an unconscious disciple of free love, the doctrine of his forefathers. Polygamy harmonized with his idea of unhampered domestic happiness; monogamy was distasteful, restrictive, and not an inherited instinct.

Cato died at the McDowell homestead in Iredell county in 1862. On his death bed, the loyal, trusting fellow expressed the hope of going direct to heaven. He said he was satisfied, because he had acted throughout his life the best he knew how to act, and that was the consensus of opinion among those who had always known him.

Hannibal was the last survivor of that wagon load of black boys. In 1865, when he heard of the emancipation, he went hobbling around the yard, shouting in a cracked voice, “Thank God, I’se free, I’se free.” The helpless old creature, then long past his prime, was incapable of realizing any emancipation save that of death. He was properly cared for by his old master during his remaining years, then came his burial.

Whether the imported Africans were procured by force, stealth or the connivance of mercenary parents, matters not. They were rescued from surroundings of idol-worship, human sacrifice and cannibalism. The slave sailing vessel unloaded her entire human freight in Charleston; and the ship of the overland, the pioneer road wagon from North Carolina, received a portion of the cargo. The inmates of that conveyance easily adapted themselves to circumstances and environments; and within the space of a life time, made considerable progress towards civilization. Transplanted to Lincoln county, N. C. from the awful simplicity of the jungles of the “Dark Continent,” and under the guidance of superior minds in America they became useful factors in the industrial development of the Piedmont section of the Carolinas.

(- The author of this article, Franklin Brevard McDowell, was a lawyer, former mayor of Charlotte (1887-1891) and a founder of the Dilworth community. A former state senator, he was the great grandson Capt. Alexander Brevard.[http://www.denverncnews.com/?p=1022])

No comments:

Post a Comment