RON'S RANT: Some of the most disturbing images of enslavement involve human beings forced to labor like animals. Men, women and even children carrying around able-bodied people irritates the stew out of me. Then these same rich bastards who stole the land, labor and natural resources of these enslaved people, contemptuously turn around and label them as "lazy," "stupid," and "subhuman." After all the visuals seems too ironic for comment. Who is the lazy person in this picture, the barefooted slave who walks around in the blazing heat of the tropical sun dressed in full tails and a top hat, while he's lugging around the dead-weight of the idle rich (stolen wealth); Or the slave monger who is too stingy to purchase a donkey, mule, horse or a cart?

I'll never understand, nor empathize with the entitlement mentality that seems to infect the wealthy thieves of humanity. Certainly the idle rich prefer to be treated like demigods, when they act like demagogic demons. Who gave them the right to own other human beings?

In A People's History of the United States, Chapter 1: Columbus, the Indians , and Human Progress, historian Howard Zinn writes: In Book Two of his History of the Indies, Las Casas (who at first urged replacing Indians by black slaves, thinking they were stronger and would survive, but later relented when he saw the effects on blacks) tells about the treatment of the Indians by the Spaniards. It is a unique account and deserves to be quoted at length:

Endless testimonies . .. prove the mild and pacific temperament of the natives.... But our work was to exasperate, ravage, kill, mangle and destroy; small wonder, then, if they tried to kill one of us now and then.... The admiral, it is true, was blind as those who came after him, and he was so anxious to please the King that he committed irreparable crimes against the Indians....

Las Casas tells how the Spaniards "grew more conceited every day" and after a while refused to walk any distance. They "rode the backs of Indians if they were in a hurry" or were carried on hammocks by Indians running in relays. "In this case they also had Indians carry large leaves to shade them from the sun and others to fan them with goose wings."

Total control led to total cruelty. The Spaniards "thought nothing of knifing Indians by tens and twenties and of cutting slices off them to test the sharpness of their blades." Las Casas tells how "two of these so-called Christians met two Indian boys one day, each carrying a parrot; they took the parrots and for fun beheaded the boys."

The Indians' attempts to defend themselves failed. And when they ran off into the hills they were found and killed. So, Las Casas reports, "they suffered and died in the mines and other labors in desperate silence, knowing not a soul in the world to whom they could turn for help." He describes their work in the mines:

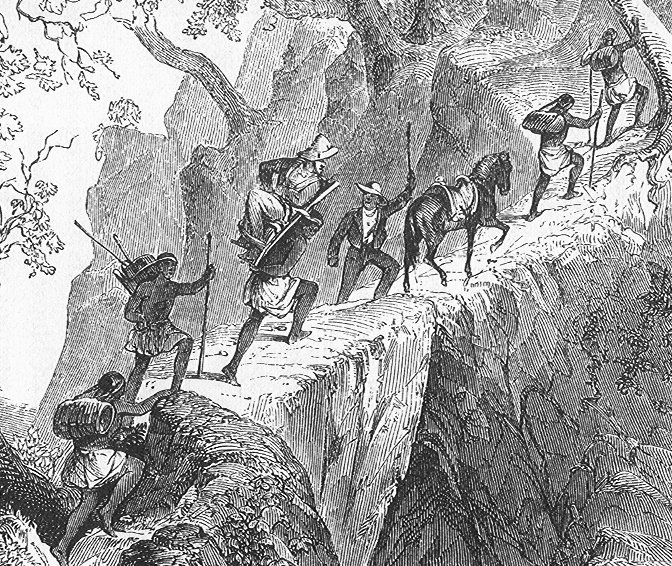

... mountains are stripped from top to bottom and bottom to top a thousand times; they dig, split rocks, move stones, and carry dirt on their backs to wash it in the rivers, while those who wash gold stay in the water all the time with their backs bent so constantly it breaks them; and when water invades the mines, the most arduous task of all is to dry the mines by scooping up pansful of water and throwing it up outside....

After each six or eight months' work in the mines, which was the time required of each crew to dig enough gold for melting, up to a third of the men died.

While the men were sent many miles away to the mines, the wives remained to work the soil, forced into the excruciating job of digging and making thousands of hills for cassava plants.

Thus husbands and wives were together only once every eight or ten months and when they met they were so exhausted and depressed on both sides ... they ceased to procreate. As for the newly born, they died early because their mothers, overworked and famished, had no milk to nurse them, and for this reason, while I was in Cuba, 7000 children died in three months. Some mothers even drowned their babies from sheer desperation.... in this way, husbands died in the mines, wives died at work, and children died from lack of milk . .. and in a short time this land which was so great, so powerful and fertile ... was depopulated. ... My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature, and now I tremble as I write. ...

When he arrived on Hispaniola in 1508, Las Casas says, "there were 60,000 people living on this island, including the Indians; so that from 1494 to 1508, over three million people had perished from war, slavery, and the mines. Who in future generations will believe this? I myself writing it as a knowledgeable eyewitness can hardly believe it...."

Thus began the history, five hundred years ago, of the European invasion of the Indian settlements in the Americas. That beginning, when you read Las Casas-even if his figures are exaggerations (were there 3 million Indians to begin with, as he says, or less than a million, as some historians have calculated, or 8 million as others now believe?)-is conquest, slavery, death. When we read the history books given to children in the United States, it all starts with heroic adventure-there is no bloodshed-and Columbus Day is a celebration.

Past the elementary and high schools, there are only occasional hints of something else. Samuel Eliot Morison, the Harvard historian, was the most distinguished writer on Columbus, the author of a multivolume biography, and was himself a sailor who retraced Columbus's route across the Atlantic. In his popular book Christopher Columbus, Mariner, written in 1954, he tells about the enslavement and the killing: "The cruel policy initiated by Columbus and pursued by his successors resulted in complete genocide." (Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States, Chapter 1: COLUMBUS, THE INDIANS, AND HUMAN PROGRESS)

An upper class woman being transported in her sedan chair by two slaves, each dressed in livery but barefoot; they follow a white man, dressed in the same colors, but who is wearing shoes. The matching colors of the clothing and the sedan chair indicate they all belong to the same owner or property. Born in Italy ca. 1740, Juliao joined the Portuguese army and traveled widely in the Portuguese empire; by the 1760s or 1770s he was in Brazil, where he died in 1811 or 1814. For a detailed analysis and critique of Juliao's figures as representations of Brazilian slave life, as well as a biographical sketch of Juliao and suggested dates for his paintings, see Silvia Hunold Lara, Customs and Costumes: Carlos Juliao and the Image of Black Slaves in Late Eighteenth-Century Brazil (Slavery & Abolition, vol. 23 [2002], pp. 125-146).

Carrying a Sedan Chair (Palanquin), Brazil, 1816 (Image Reference: KOSTER1)

Caption, "A lady going to visit". The Brazilian scholar, Gilberto Freyre writes: "Within their hammocks and palanquins the gentry permitted themselves to be carried about by Negroes for whole days at a time, some of them travelling in this manner from one plantation to another, while others employed this mode of transport in the streets; when acquaintenances met, it was the custom to draw up alongside one another and hold a conversation" (The Masters and the Slaves [New York, 1956], pp. 409-410, 428). (In the 2nd ed. [London, 1817], all images are in b/w.)

This aquatint entered the collections of the V&A Museum as part of a group of ‘illustrations of carriages’ in 1860. It depicts a white woman being carried in a sedan chair by two black liveried servants. The party is led by a young black man, similarly wearing livery. The setting is a street scene, probably a town or city in Brazil. Brazil imported more enslaved African people than any other colony in the Americas. Unlike other colonies where most Africans were confined to manual labour on plantations, in Brazil many worked in urban occupations, including as domestic servants.

Images of the New World became available to the European public through the publication of travel narratives by Spanish, French, English, Portuguese, Italian and Dutch explorers from the 16th century. Many were accompanied by illustrations, often based on first hand observations. Hugely popular, these illustrations were widely copied during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Carrying a Sedan Chair or Palanquin, Ile De France (Mauritius), 1818 (Image Reference: frey2)

Caption: "Ile de France: Palanquin." Shows four men (slaves?) carrying a palanquin or covered litter; on the right, a man is being shaved by a barber by the side of what appears to be a wood plank house. The palanquin is described in the list of plates as a "sorte de voiture sans roues, a l'usage des colons riches du pays. Vue prise a l'ile de France." (A type of carriage/coach used by the rich [white] colonists of this country".) This engraving was published in an elaborate Atlas of 112 plates, some in color, based on drawings made by various artists during a French geographical expedition in the early nineteenth century; the expedition visited Ile de France in May 1818. (The Atlas accompanies a multi-volume account of the expedition, and is sometimes cataloged under the authorship of "Ministere de la Marine et des Colonies [France]," rather than Freycinet, the commander of the expedition. ) Ile de France, in the Indian Ocean, was renamed Mauritius, its current name, when the British captured the island from the French in 1810.

Carrying a Covered Hammock, Bahia, Brazil, 1712-1714 (Image Reference: frezier01)

Two slaves transporting a merchant or planter in a covered hammock; on the right, another slave (?) carries the European's sword and an umbrella to shield him from the sun when he alights. The author describes this scene: "Rich people, even if it is inconvenient, hardly ever walk. They are always industrious in finding ways to distinguish themselves from other men. In America, as in Europe, they are ashamed to use the legs that nature has given us for walking. They are gently carried in beds of woven cotton, suspended at both ends on a large pole that two blacks carry on their heads or on their shoulders. And being hidden there so that the rain or ardor of the sun cannot make them uncomfortable, this bed is covered with a fringe of gold hanging from curtains that one can close when one wants. There, comfortably laying down, the head supported by a bolster of luxurious fabric, they are carried comfortably . . . These cotton hammocks are called Serpentin and are not Palanquins, as some travelers call them" (Frézier, p. 526; our translation). The Brazilian scholar, Gilberto Freyre, writes: "Within their hammocks and palanquins the gentry permitted themselves to be carried about by Negroes for whole days at a time, some of them travelling in this manner from one plantation to another . . . . Nearly all [slaveholders] travelled by hammock . . ." (The Masters and the Slaves [New York, 1956], pp. 409-410, 428)

Carrying a Sedan Chair (Palanquin), Brazil, 1820s (Image Reference: GRA3)

Caption "cadeira, or sedan chair of Bahia"; two domestic servants (slaves) carrying a European woman. The Brazilian scholar, Gilberto Freyre writes: "Within their hammocks and palanquins the gentry permitted themselves to be carried about by Negroes for whole days at a time, some of them travelling in this manner from one plantation to another, while others employed this mode of transport in the streets; when acquaintenances met, it was the custom to draw up alongside one another and hold a conversation" (The Masters and the Slaves [New York, 1956], pp. 409-410, 428).

Caption, "A Brazilian sedan-chair and a person begging for the church"; white woman being carried by two liveried male servants; urban scene. The Brazilian scholar, Gilberto Freyre writes: "Within their hammocks and palanquins the gentry permitted themselves to be carried about by Negroes for whole days at a time, some of them travelling in this manner from one plantation to another, while others employed this mode of transport in the streets; when acquaintenances met, it was the custom to draw up alongside one another and hold a conversation" (The Masters and the Slaves [New York, 1956], pp. 409-410, 428).

Carrying a Sedan Chair (Palanquin), Brazil, 1853 (Image Reference: HW9-731)

Caption, "Brazilian Sedan"; two formally attired male slaves carrying the palanquin, followed by several female slaves. The Brazilian scholar, Gilberto Freyre writes: "Within their hammocks and palanquins the gentry permitted themselves to be carried about by Negroes for whole days at a time, some of them travelling in this manner from one plantation to another, while others employed this mode of transport in the streets; when acquaintenances met, it was the custom to draw up alongside one another and hold a conversation" (The Masters and the Slaves [New York, 1956], pp. 409-410, 428).

Transporting a Planter in a Hammock, Brazil, 1816-1831 (Image Reference: NW0127)

. . . . Nearly all [slaveholders] travelled by hammock . . ." (The Masters and the Slaves [New York, 1956], pp. 409-410, 428). The engravings in this book were taken from drawings made by Debret during his residence in Brazil from 1816 to 1831. For watercolors by Debret of scenes in Brazil, some of which were incorporated into his Voyage Pittoresque, see Jean Baptiste Debret, Viagem Pitoresca e Historica ao Brasil (Editora Itatiaia Limitada, Editora da Universidade de Sao Paulo, 1989; a reprint of the 1954 Paris edition, edited by R. De Castro Maya).

Transporting a Planter's Wife in a Hammock, Brazil, 1816 (Image Reference: NW0128)

Caption, "A Planter and his Wife on a Journey." Two slaves carrying a covered hammock while the planter rides his horse; a slave woman carries their baggage on her head. The Brazilian scholar, Gilberto Freyre writes: "Within their hammocks and palanquins the gentry permitted themselves to be carried about by Negroes for whole days at a time, some of them travelling in this manner from one plantation to another . . . . Nearly all [slaveholders] travelled by hammock . . ." (The Masters and the Slaves [New York, 1956], pp. 409-410, 428). In the 2nd ed. (London, 1817), all images are in b/w. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (Williamsburg, Virginia) also has a copy of this print.

Carrying a Sedan Chair (Palanquin), Bahia, Brazil, 1826 (Image Reference: NW0317)

Urban scene in Bahia, showing servants/slaves carrying a white woman. The Brazilian scholar, Gilberto Freyre writes: Within their hammocks and palanquins the gentry permitted themselves to be carried about by Negroes for whole days at a time, some of them travelling in this manner from one plantation to another, while others employed this mode of transport in the streets; when acquaintenances met, it was the custom to draw up alongside one another and hold a conversation" (The Masters and the Slaves [New York, 1956], pp. 409-410).

Slaves Carrying a Covered Hammock, Brazil, 1630s (Image Reference: NW0320)

White woman being carried in a covered hammock by two male slaves, white clay pipes tucked into their clothing; other slaves following on foot, carrying fruit baskets. Wagener/Wagner was a German mercenary for the Dutch West India Company; in 1634, at the age of about 20, he went to northeastern Brazil and stayed there for 7 years. He writes "The wives and children of notable and wealthy Portuguese are transported in this manner, by two strong slaves, to the houses of their friends or to church; they hang the beautiful cloths of velvet or damask over poles so that the sun does not burn them strongly. They also take behind them a variety of beautiful and tasty fruits as a present for those that they wish to visit" (vol. 2, p. 190).

Transporting a Covered Hammock, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1819-1820. Image Reference: vista02)

Caption, called the "Rede" this "sort of hammock," the author writes, is "usually made of cotton net, dyed of various colours and fringed, in which females, a little above the lower classes, are carried about by their slaves; it is furnished with a pillow to lean upon, and across the bamboo, from which it is suspended, is thrown a covering or curtain fantastically striped. When the lady wishes to stop, the carriers plant their sticks in the ground and support the ends of the bamboo on the iron fork fixed at the end of each for that purpose, until their mistress chooses to proceed." On the right, a male slave is carrying a load of "Capim or Guinea Grass" while on the left, the woman carrying her child is selling pineapples (pp. 202-203). The foreground figures in Chamberlain's book were copied from three separate water-colors drawn earlier by Joaquim Candido Guillobel. Born in Portugual in 1787, Guillobel came to Brazil in 1808, and from 1812 started "drawing and painting small pictures on cards of everyday scenes in Rio de Janeiro." For biographical details on Guillobel, who died in 1859, and reproductions of about 60 of his original drawings in color (including the ones shown here), see Joaquim Candido Guillobel, Usos e Costumes do Rio de Janeiro nas figurinhas de Guillobel [1978]. The text of this volume is given in both Portuguese and English; the author of the biographical notes who is, presumably the compiler of the volume, is not given in the Library of Congress copy that was consulted. (See this website, "Chamberlain" for related drawings.)

Carrying a Sedan Chair (Palanquin), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1819-1820 (Image Reference: vista09)

Title, "The Seje, or Chege, and Cadeira." The "Cadeira" (right) "consists of an arm chair, with a high back, firmly fixed upon a foot board, having an oblong wooden top from which hang curtains . . . . The bearers were chosen from the stoutest and best looking negroes in the family, and were dressed in gay liveries; sometimes wearing coloured feathers in their hats." On the left, is the "Chaise, or Chégé," driven by two other slaves in livery. The foreground figures in Chamberlain's book were copied from two separate water-colors drawn earlier by Joaquim Candido Guillobel. Born in Portugual in 1787, Guillobel came to Brazil in 1808, and from 1812 started "drawing and painting small pictures on cards of everyday scenes in Rio de Janeiro." For biographical details on Guillobel, who died in 1859, and reproductions of about 60 of his original drawings in color (including the ones shown here) see Joaquim Candido Guillobel, Usos e Costumes do Rio de Janeiro nas figurinhas de Guillobel [1978]. The text of this volume is given in both Portuguese and English; the author of the biographical notes who is, presumably the compiler of the volume, is not given in the Library of Congress copy that was consulted. (See this website, "Chamberlain" for related drawings.) www.slaveryimages.org, compiled by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite, and sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library."

As a modern young lady I would say that this kind of transport in former times was absolutely reasonable and made sense.

ReplyDeleteI would never say that this has been a kind of an abuse.

Today I think we would no longer need sedan-chairs but I would also like to underline that even the job as a porter of a sedan-chair was a possibility to earn money.

Nonsense! If they were paid and had shoes you might have a point. Just shows how lazy and abusive white colonialists were.

Delete'Modern' (white) women walking barefoot for miles on rough terrain in extreme weather conditions carrying able bodied shod African men is perfectly reasonable and make sense too! It all depends on the context.

Delete'Modern' (white) women walking barefoot for miles on rough terrain in extreme weather conditions carrying able bodied shod African men is perfectly reasonable and makes sense too! It all depends on the context.

DeleteIt would be as reasonable and make perfect sense if the 'modern' (white) women described above were unpaid, beaten slaves forced to carry able bodied shod African men barefoot for miles on rough terrain and in extreme weather conditions day in day out for years! It just depends on the context.

DeleteAre you saying that you, as a modern young lady would love to be carried by male slaves? I would say that this kind of transport would be ok if I agree to carry You. And yes, I would agree to carry a modern young lady if this makes her happy.

Delete'Modern' (white) men walking barefoot for miles on rough terrain in extreme weather conditions carrying African Women is perfectly reasonable and makes sense too! It all depends on the context.

DeleteThis is the one of the best and informatic blogspot i ever seen.thanks for such a nice and unique content with many tips , ideas and guide to other traveler.Thanks again.

ReplyDeletetaxi service in Riverdale Georgia

With all of these accounts by the brothers of the very whit skin man proving how inhumane the white skin man of Europe has been to darker skin people, some Africans disgustingly hail them. Today, as observed and remarked by Professor Patrice Lumumba in his speech "Tragedy of Africa" Africans are not again wailing and kicking as they are being enslaved in Europe and America, but they are wailing and kicking as they seek to be enslaved in Europe and America by the same masters who treated our ancestors like beasts of burden. Today, most of our people have failed to be proud of our race and homeland and seek to reside in the lands of others forgetting to realize the fact that those lands were once as ours and the owners proudly got to work to get to where they are. Today, some Africans are rubbing creams to lighten the pigments of their skin because they do not admire thee beautiful black pigments God has blessed us with. Today, we face modern slavery and happily embrace it because we are a problem for ourselves. Nevertheless, there are few of us who believe that we are 100% humans and can do anything another group of people walking the earth can do. We can think equally as they can think and we are a gentle and strong people. When we learn to love ourselves, we shall truly see that the notion that Africans are lazy is an a thought that is false.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete