Viewed as a scathing criticism of the government that appointed an incompetent as captain of the frigate Medusa, this painting scandalized society and contributed to renewed interest in abolitionism. The ship went aground off the West African coast in 1816. With insufficient lifeboats, the captain saved himself and privileged passengers but left some 150 men adrift on a hastily constructed raft. Only 15 of those men survived the ordeal. The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault (1791-1824). 1819. Oil on canvas. Louvre, Paris, France.

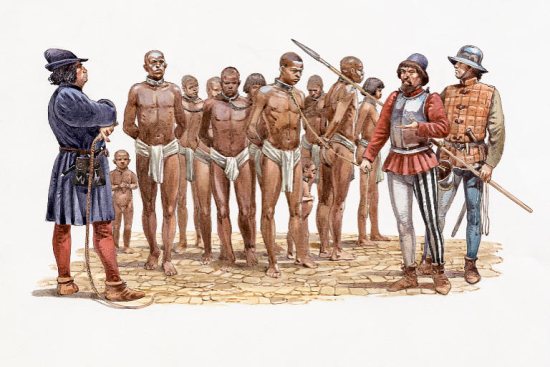

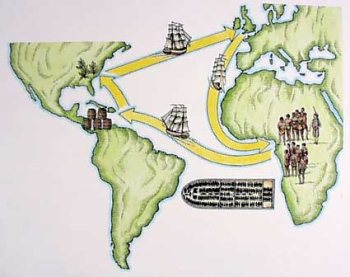

The social and economic life of these four French colonies was shaped by the first settlers and by the slave-owning planters, then by the sugar manufacturers, in the course of the 18th and 19th centuries and the beginning of the 20th century. These colonies witnessed slavery and the slave trade, which supplied them with labor for nearly three centuries. Since the plantations took a heavy toll on human life – with high slave mortality – they had to be constantly repopulated.

After a brief period of freedom in Guadeloupe, which lasted from 1794 to 1802 during the peak of the French Revolution, slavery was re-established. It was finally officially abolished by the provisional government established in Paris by the revolution of 1848.

However, it took demonstrations and riots to force the governors of Martinique and Guadeloupe to apply this decision and proclaim the immediate abolition of slavery. The provisional government also established universal suffrage and for a short period (1848-51) there were elections in the two islands. Republicans, who fought to abolish slavery, were opposed to Conservatives, who thought that the blacks already had too many rights and that abolition of slavery was detrimental to work on the plantations.

The old plantation owners did not accept the new freedoms granted to their former slaves. The plantation owners were represented by stooges recruited among the earliest freed slaves, whereas the "Republicans" or "Schoelcherists" – named after the 1848 abolitionist – generally were supported by the mulattos and the blacks. Schoelcher himself was elected several times as a deputy in Martinique and Guadeloupe.

But blacks did not start playing a part in political life at that time. It was outsiders like Schoelcher or mulattos who presented themselves as the representatives of the interests of the black population.

A black party did not appear until 1891 when the first socialist party was created in Guadeloupe, led by a black man, H. Légitimus. This party presented itself as the black people's party. A few years later, in 1901, the Martinique socialists, led by Lagrosillière, joined the French Socialist Party.

The two Socialist Parties, that of Légitimus and that of Lagrosillière in Martinique, underwent a similar evolution. Having won municipal, legislative and cantonal elections – very easily in Guadeloupe and with more difficulty in Martinique – the socialists sat as elected representatives in the local assemblies and sent socialist deputies to France under the Third Republic.

Like the opportunist wing of the Socialist Party, the leaders of these two West Indian parties wanted to find a place in the bourgeois government. In 1902 Légitimus declared the need for an agreement between capital and labor. He was followed in this by Lagrosillière in 1919. The socialists were concerned mainly with electoral success, making various alliances with representatives of the capitalists.

Nonetheless, throughout this period, there were a few strikes, in some cases in opposition to the wishes of the Socialists. The great François strike of 1900 in Martinique was followed by the 1910 general strike by farm laborers in Guadeloupe. During the years which followed, up to World War II, there were constant strikes by farm laborers and sugar workers, often harshly repressed by colonial troops.

Throughout this period, the former slaves, now "free" workers, lived under brutal exploitation. Although free, many remained tied to the plantations because they received hardly any money, being constantly indebted to the bosses who paid them in vouchers or tokens enabling them to buy supplies in shops belonging to the bosses or under their control. Some workers lived on the plantation in "negro cabins" belonging to the plantation owner. The former slave-drivers were transformed into managers or accountants who controlled workers' whole lives. This whole situation meant that there were enormous social and political pressures on the workers when there were strikes or elections.

Poor hygiene conditions and intestinal diseases led to high infant mortality. Tropical diseases like malaria were common. Alcoholism was widespread, since rum was the product poor people could most easily buy.

Education was introduced very slowly, and was provided by private institutions reserved more for the rich and well-off mulattos than for the children of the poor. Education began to become public at the same time as in France, around the 1880s, but at a much slower pace. The first West Indian socialists had made education one of the main aims of their political struggles, but this aim served to distract people from further struggle. The wish to be integrated into France manifested itself first of all in the belief, very firmly ingrained in all poor blacks, that their future depended primarily on education. Poor people made major sacrifices to get their children out of the cane fields and factories and off the plantations. It was thought necessary to study in order to become at least an office worker or a town worker.

This attitude was based on a powerful illusion, for wage- earners in the towns did not enjoy a much more enviable fate, apart from the fact that they escaped the harshness of the cane harvest. In town, most workers lived in vile and crowded accommodations. The crowding encouraged the development of all kinds of diseases and personal conflicts, and it grew constantly worse because, after each crisis or concentration of the sugar industry, unemployment grew and drove country people toward the towns. Fires were frequent and often burned down whole sections of towns, since all the cabins were made of wood.

These districts were not renovated until the 1960's! [http://the-spark.net/csart124.html]

No comments:

Post a Comment