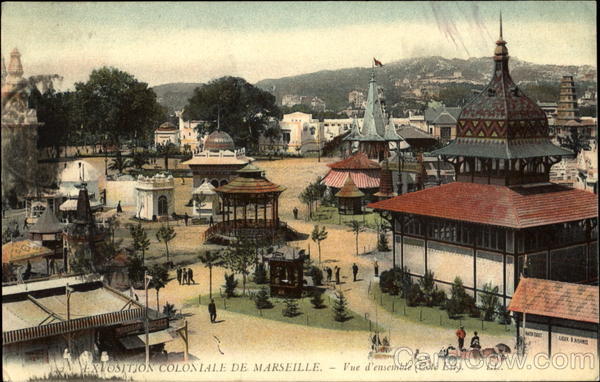

HIDDEN PARIS: Paris’s Forgotten Human Zoo," 16 February 2011, by Clea Caulcutt: At Vincennes, on the edge of Paris, visitors may stumble across the relics of the 1907 colonial expo in which men and women from the former colonies were exhibited to crowds of visitors. French authorities have neglected the site, a sombre reminder of Europe’s colonial past, which is now in danger of being irreparably lost.

The Gallic rooster at the entrance of the Jardin tropical has seen better days. Once destined to preside over one of Paris’s main avenues, the central figure of the Monument to the glory of colonial expansion has lost a leg and is now covered in moss. But it still stands proudly, strutting on a globe representing the earth, on a bed of weapons and travelling instruments.

Fragments of this monument have washed up in the Jardin tropical, where many hope it will be forgotten.

“It’s the junkyard of French colonial history,” says French historian Pascal Blanchard, “The memory of France's relations to its colonies over the last century is concentrated here.”

There is little logic in the site’s layout. Buildings of Paris’s 1907 colonial exhibition stand alongside memorials to colonial soldiers dead in World War I. Embarrassing reminders of a sombre period in European history, the buildings of the colonial exhibit have been left to rot away, paint peeling, roofs falling in, overrun with brambles

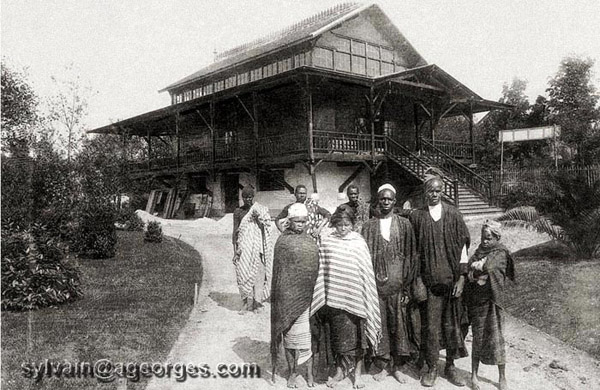

Traces of the exotic can still be found, in the shape of an etched palm tree on Benin’s pavilion, or a couple of mosaics on Tunisia’s pavilion. Typical world fair pavilions, but with a more sinister story. Many historians now call such colonial exhibits "human zoos".

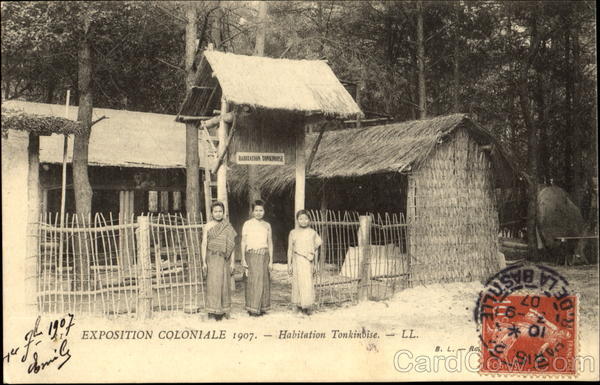

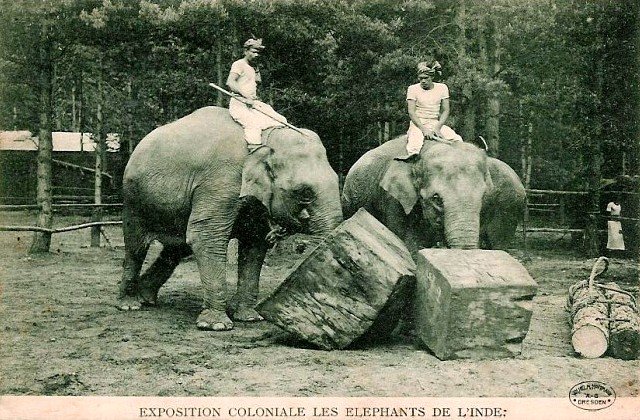

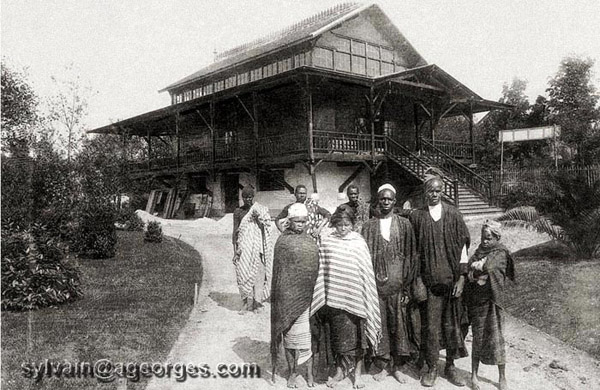

Men and women from the French colonies were brought to Europe and rented out to zoological and tropical gardens, where they were put on show alongside exotic animals.

Kanak warriors and their families were shipped over from French New Caledonia. African families were recruited in Senegal, Niger, Guinea and Dahomey (in what is now Benin) to live in replicas of their villages. They were given mock traditional costumes, and told to dance or play music for the visitors.

Such ethnological exhibitions were hugely popular at the beginning of the 20th century. They served the interests of the owners of tropical gardens seeking to spice up their shows as well as the purposes of colonial administrators and anthropologists at the time.

The Jardin tropical is the only remaining site in France where the displays have not been razed to the ground.

The garden could be a great teaching tool for historians, many say, but it remains largely unknown and ignored.

“The exhibit has been neglected. I know Parisians who have lived all their life near Vincennes and who have never once set foot in it,” says Benjamin Pelletier, a writer and intercultural management trainer.

At the beginning of the 20th century, colonial Europe staged big spectacular events to whip up enthusiasm for the colonial effort and encourage a sense of racial superiority.

“Sprinkling a couple of natives on these pavilions was their way of showing that they controlled and dominated people from the colonies,” says Blanchard.

And the crowds loved it.

One million people trekked through the colonial exhibition in 1907. Blanchard estimates that one and a half billion people visited universal or colonial exhibits throughout the world from 1870 to 1930.

For the visitors, going to the colonial exhibitions was akin to going to the circus, with exotic freak shows on offer for a couple of francs. Postcards show women gushing over African babies and men ogling bare-breasted African women, writes art historian Isabelle Levêque.

Men and women from the colonies were lured into joining paid troupes that toured international exhibitions from Marseille to New York, where they were exploited by agents, colonial administrators or village chiefs.

“It was a business, straightforward capitalism,” says Blanchard. “The natives on show were free and they were paid to take part in the show but they were oppressed by the visitor's gaze which forced them into a role that was not theirs. And this role gave visitors the impression they were looking at someone who was a symbol of a race.”

Degrading living conditions, disease and low temperatures meant that many died on tour. At Paris’s Jardin d’acclimatation, 27 men and women died on show and were buried in the garden, says Blanchard.

Far from condemning such exhibitions, scientists and anthropologists grabbed this opportunity to study the families on display and collect data for their work, much of which contributed to the racial theories of the period.

One hundred years later, the exhibit is an example of the pervasive racism at the time, a time France wants to forget.

“It's a clear sign of our collective amnesia," says Blanchard, “and it’s here you can see our memory decaying in front of our eyes. The French state, the local authorities, the Paris town council, they are all responsible and they have all agreed to do absolutely nothing.”

It is surprising that France, usually so proud of its heritage, has neglected the Jardin tropical, says writer Pelletier. He believes the Paris town council is caught in a double bind.

“They daren’t restore or enhance the site, because that would be tantamount to elevating a sombre chapter in French history,” he says, “On the other hand, they daren’t destroy it because the site is now part of our heritage.”

“Soon afterwards, the Paris mayor said he didn’t want to fund the restoration of the garden,” says Contassot, a member of the Green Party. “He was very clear, if people want to pay for it, they can, but it was not his priority.”

The Paris city council denies there was any backtracking and says one million euros was allocated to renovating the Indochina pavilion which is to be completed this year. The town hall is currently seeking partnerships to renovate the rest of the Jardin tropical.

The renovation project will not explore the details of the exhibition of human beings during the 1907 colonial exhibition, it says.

Nothing will be hidden, the council says, but it prefers to promote good relations between the northern and the southern hemisphere.

But reluctance to act means the site is disintegrating rapidly. In 2004, Congo’s pavilion was destroyed in a fire.

“This indecision is harmful, because the weather is taking its toll on the pavilions and they are disappearing,” says Pelletier. [source: http://www.english.rfi.fr/france/20110216-paris-s-forgotten-human-zoo-shows-crude-workings-colonial-propaganda]

No comments:

Post a Comment