From The New York Times, on 4 January 2008, in the Books Of The Times section's article entitled, "Early Warriors in the Fight for Racial Equality," by David J. Garrow --- “In the three decades that followed World War I, black Southerners and their allies relentlessly battled Jim Crow,” Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore writes at the outset of this rich but sprawling book. Ms. Gilmore, a professor of history at Yale, wants her “collective biography of activist black and white Southerners” from that era to illuminate how resistance to the South’s elaborate system of racial segregation, often nicknamed Jim Crow after a 19th-century minstrel song, long predated the onset of traditionally celebrated civil-rights initiatives in 1954-55.

Lawrence Textile Strike, 1912

Ms. Gilmore begins her story at the end of World War I, when “the virulence of discrimination during the war and the racial violence afterward transformed African-Americans’ political consciousness” and stimulated a new generation of activists. Southern officialdom was violently intolerant of such dissenters, and in most instances “those who openly protested white domination had to leave” the region.

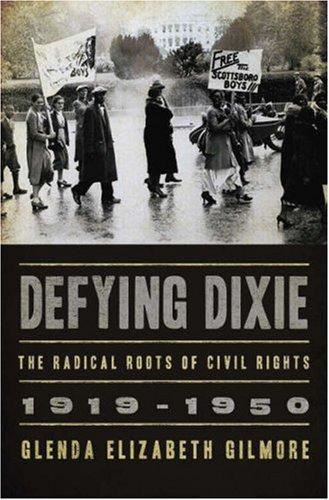

DEFYING DIXIE: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950, by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore

“The South could remain the South only by chasing out some of its brightest minds and most bountiful spirits, generation after generation,” Ms. Gilmore writes.

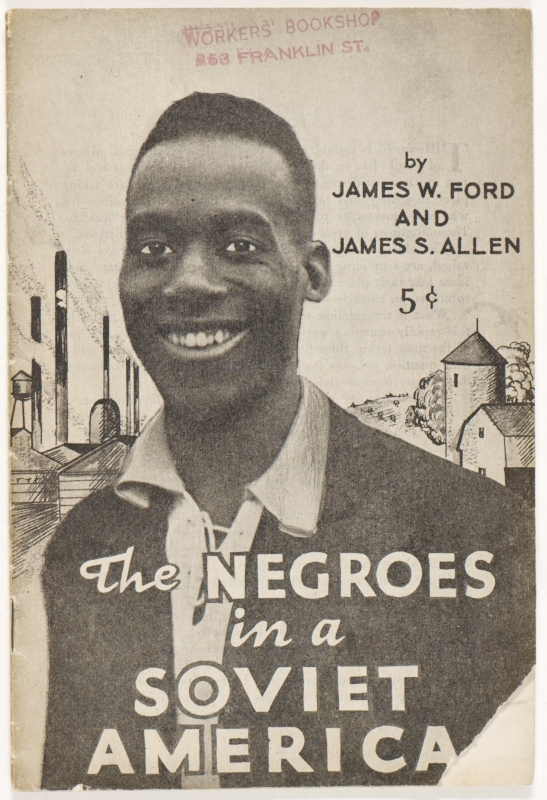

The first focal figure in “Defying Dixie” is Lovett Fort-Whiteman, a widely traveled Texan who in 1919 became “the first American-born black Communist.” Ms. Gilmore devotes considerable attention to such early Soviet true-believers, few though they were, for “in the 1920s and 1930s the Communists alone argued for complete equality between the races,” she notes. “Their racial ideal eventually became America’s ideal.”

She also reports how Soviet loyalties led some crusaders to tragic ends: Fort-Whiteman died in a Siberian prison labor camp in 1939 after moving to Moscow and getting caught up in the Stalinist purges.

Ms. Gilmore rightly stresses that even as late as the 1940s, mainstream interracial groups like the Southern Regional Council “did not endorse desegregation.” Her indictment of “the bankruptcy of moderate organizations” and moderate white Southern academics is powerful and profound.

But “Defying Dixie” sometimes assumes that readers are already familiar with a panoply of otherwise unidentified groups and individuals: One page makes a passing reference to “the 1880s Knights of Labor Constitution,” and the next presumes knowledge of both Eugene V. Debs and Upton Sinclair. Ms. Gilmore also sometimes speeds past an event that cries out for more explanation, as when she devotes only a brief paragraph to what she calls “the first Southern interracial conference that dared endorse integration.”

By far the most compelling portions of “Defying Dixie” tell the life story of Pauli Murray, a black lesbian feminist whose lifelong activism began with an unsuccessful attempt to desegregate the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in early 1939 and culminated with her ordination as an Episcopal priest in 1977. Ms. Murray’s application to North Carolina’s graduate school came shortly after lawyers for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had won its first higher-education desegregation case in the United States Supreme Court. But Ms. Gilmore reveals how the N.A.A.C.P. counsel Thurgood Marshall was unwilling to pursue Ms. Murray’s challenge because of his disquiet over both her sexuality and her past membership in a communist splinter group that opposed the Communist Party itself.

Eleven years went by before Marshall won a pair of Supreme Court cases that mirrored Ms. Murray’s complaint, and Ms. Gilmore muses about how costly that delay was. “Had the N.A.A.C.P. been able to win desegregation decisions in World War II America, white Southerners would have had a more difficult time mounting massive resistance in the midst of a war against intolerance,” when claims of black inferiority “seemed to have more in common with the Führer than with the Founders.”

Instead the legal confrontation took place in the 1950s, when the Southern allegation “that integrationists were Communists” carried far greater resonance than it would have a decade earlier, and when “the power of the left to implement desegregation” — as Ms. Gilmore imagines it — no longer existed.

Ms. Gilmore’s speculation implausibly presumes that the Supreme Court would have invalidated school segregation earlier than it did. She rightly emphasizes, though, how the surprising Nazi-Soviet Pact of August 1939 destroyed the left-liberal Popular Front and upended the Southern left’s argument that Jim Crow represented American fascism. Instead segregationists could use American Communists’ subservience to Moscow to tar their liberal and socialist allies as fellow travelers. When evidence of Communist complicity in Soviet espionage began to emerge after the war’s end, it was leftists, not white supremacists, who could now be painted as downright un-American.

That postwar reversal, Ms. Gilmore argues, “removed white liberal forces from Southern politics at the very moment that they were crucial to the extension of meaningful political and civil rights to the vast majority of black Southerners.”

“Defying Dixie” should more pointedly blame Soviet behavior for the Southern left’s demise, and when Ms. Gilmore says that postwar conservatives, “masquerading as anti-communist ... were actually antiliberal,” she errs, for there was no fakery: Opponents of racial equality and liberal programs were sincerely anti-Communist as well.

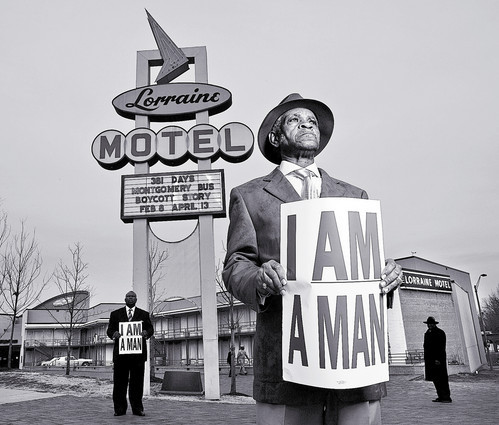

Ms. Gilmore forthrightly acknowledges that “Defying Dixie” “slights the local people who lived in the South and who started the civil rights movement in the 1950s.” However, she rashly claims that too much emphasis on the 1950s overstates the movement’s “religious, middle-class and male roots” and fosters the notion “that middle-class black men in ties radicalized the nation” — an extravagant straw man, given how women like Jo Ann Robinson and Ella Baker are now so widely heralded for their crucial roles in the upsurge that took wing between 1955 and 1960.

Yet Ms. Gilmore is certainly correct when she concludes that her book’s courageous radicals “may not have been able to take credit for that civil rights movement, but they knew in their hearts that they had helped pave the way for it.” [source: The New York Times; David J. Garrow, a senior fellow at Homerton College, University of Cambridge, is the author of “Bearing the Cross,” a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.]

No comments:

Post a Comment