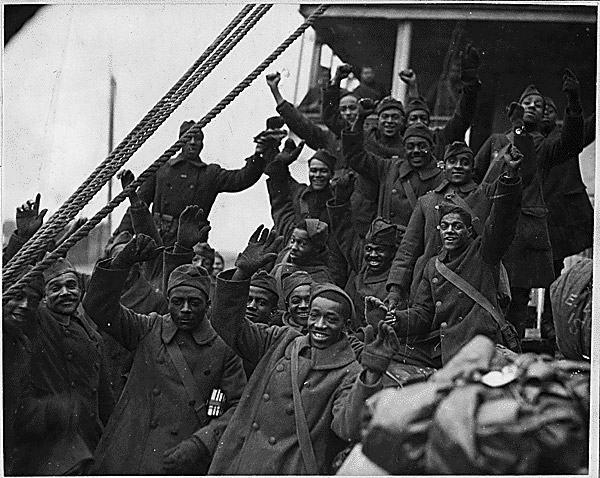

New York's famous 369th regiment arrives home from France, 1919.

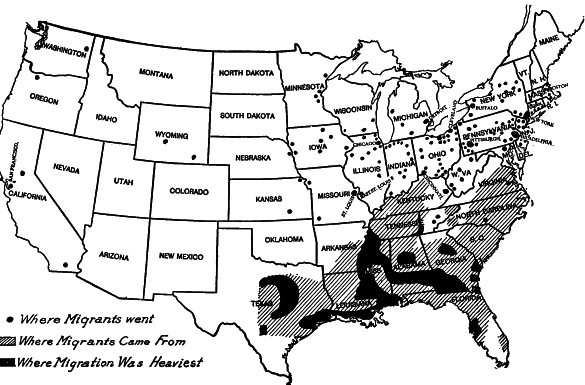

NEGRO MIGRATION DURING THE WAR

CHAPTER VI--The Draining of the Black Belt

In order better to understand the migration movement, a special study of it was made for five adjoining States, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, from which came more than half of all migrants. The negro population of these five States was 4,115,299, which was almost half of the negro population of the South. In the particular sections of these States where the migration was the heaviest, the one crop system, cotton, was general. As a result of the cotton price demoralization resulting from the war, the labor depression, the ravages of the cotton boll weevil, and in some regions unusual floods, as already stated, there was in this section of the South an exceptionally large amount of surplus labor. The several trunk line railroads directly connecting this section with the northern industrial centers made the transportation of this labor an easy matter.

In 1915, the labor depression in Georgia was critical and work at remunerative wages was scarce. In Atlanta strong pressure was brought to bear to have the negroes employed in cleaning the streets replaced by whites who were out of work. It was reported that the organized charities of Macon, in dealing with the question of the unemployed, urged whites employing negroes to discharge the blacks and hire whites. Mr. Bridges Smith, the mayor of the city, bitterly opposed this suggestion. When the 1915 cotton crop began to ripen it was proposed to compel the unemployed negroes in the towns to go to the fields and pick cotton. Commenting editorially on this, the Atlanta Constitution said:

The problem of the unemployed in Albany, Georgia, is being dealt with practically. All negroes who have not regular employment are offered it in the cotton fields, the immense crop requiring more labor than the [pg 60] plantations ordinarily have. If the unemployed refuse the opportunity, the order "move on" and out of the community is given by the chief of police, and the order must be obeyed. Though the government is taking up very systematically the problem of the unemployed, its solving will be slow, and the government aid for a long time will have to be supplementary to work in this direction, initiated in communities, municipalities and States, where the problem of the unemployed is usually complex.62

In the course of time, when the negroes did leave, they departed in such large numbers that their going caused alarm. Because they left at night the number of negroes going north from the immediate vicinity was not generally realized. One night nearly fifty of Tifton boarded northbound passenger trains, which already carried, it is said, some three hundred negroes. Labor agents had been very active in that section all fall, but so cleverly had they done their work that officers had not been able to get a line on them. For several weeks, the daily exodus, it is said, had ranged from ten to twenty-five.63

Columbus was an assembling point for migrants going from east Alabama and west Georgia. Railroad tickets would be bought from local stations to Columbus, and there the tickets or transportation for the North, mainly to Chicago, would be secured. Americus was in many respects similarly affected, having had many of its important industries thereby paralyzed. Albany, a railroad center, became another assembling point for migrants from another area. Although difficulties would be experienced in leaving the smaller places directly for the North, it was easy to purchase a ticket to Albany and later depart from that town. The result was that Albany was the point of departure for several thousand negroes, of whom a very large percentage did not come from the towns or Dougherty county in which Albany is situated.64

A negro minister, well acquainted with the situation in southwest Georgia, was of the opinion that the greatest number had gone from Thomas and Mitchell counties and the towns of Pelham and Thomasville. Valdosta, with a population of about 8,000 equally divided between the races became a clearing house for many migrants from southern Georgia. The pastor of one of the leading churches said that he lost twenty per cent of his members. The industrial insurance companies reported a twenty per cent loss in membership.65 Waycross,66 a railroad center in [pg 62] the wire grass section of the State, with a population of 7,700 whites and 6,700 negroes, suffered greatly from the migration. Hundreds of negroes in this section were induced by the employment bureaus and industrial companies in eastern States to abandon their homes. From Brunswick, one of the two principal seaports in Georgia, went 1,000 negroes, the chief occupation of whom was stevedoring. Savannah, another important seaport on the south Atlantic coast, with a population of about 70,000, saw the migration attain unusually large proportions, so as to cause almost a panic and to lead to drastic measures to check it.

The migration was from all sections of Florida. The heaviest movements were from west Florida, from Tampa and Jacksonville. Capitola early reported that a considerable number of negroes left that vicinity, some going north, a few to Jacksonville and others to south Florida to work on the truck farms and in the phosphate mines. A large number of them migrated from Tallahassee to Connecticut to work in the tobacco fields. Owing to the depredations of the boll weevil, many others went north. Most of the migration in west Florida, however, was rural as there are very few large towns in that section. Yet, although they had no such assembling points as there were in other parts of the South, about thirty or thirty-five per cent of the labor left. In north central Florida near Apalachicola fifteen or twenty per cent of the labor left. In middle Florida around Ocala and Gainesville probably twenty to twenty-five per cent of the laborers left, chiefly because of the low wages. The stretch of territory between Pensacola and Jacksonville was said to be one of the most neglected sections in the South, the migration being largely of farm tenants with a considerable number of farm owners. There were cases of the migration of a whole community including the pastor of the church.67

Live Oak, a small town in Sewanee county, experienced the same upheaval, losing a large proportion of its colored population. Dunnelon, a small town in the southern part of Marion county, soon found itself in the same situation. Lakeland, in Polk county, lost about one-third of its negroes. Not less than one-fourth of the black population of Orlando was swept into this movement. Probably half of the negroes of Palatka, Miami and De Land, migrated as indicated by schools and churches, the membership of which decreased one-half. From 3,000 to 5,000 negroes migrated from Tampa and Hillsboro county. Jacksonville, the largest city in Florida, with a population of about 35,000 negroes, lost about 6,000 or 8,000 of its own black population and served as an assembling point for 14,000 or 15,000 others who went to the North.68

By September, 1916, the movement in Alabama was well under way. In Selma there was made the complaint that a new scheme was being used to entice negroes away. Instead of advertising in Alabama papers, the schemes of the labor agents were proclaimed through papers published in other States and circulated in Alabama. As a result there was a steady migration of negroes from Alabama to the North and to points in Tennessee and Arkansas where conditions were more inviting and wages higher. Estimates appear to indicate, however, that Alabama, through the migration, lost a larger proportion of her negro population than did any one of the other southern States.69

From Eufaula in the eastern part of the State it was reported in September that trains leaving there on Sundays in 1916 were packed with negroes going north, that hundreds left, joining crowds from Clayton, Clio and Ozark. There seemed to be a "free ride" every Sunday and many were giving up lucrative positions there to go. The majority of these negroes, however, went from the country where they had had a disastrous experience with the crops of the year 1916 on account of the July floods.70 By October the exodus from Dallas county [pg 64] had reached such alarming proportions that farmers and business men were devising means to stop it.

Bullock county, with a working population of 15,000 negroes, lost about one-third and in addition about 1,500 non-workers. The reports of churches as to the loss of membership at certain points justify this conclusion. Hardly any of the churches escaped without a serious loss and the percentage in most cases was from twenty-five to seventy per cent.71 It seemed that these intolerable conditions did not obtain in Union Springs. According to persons living in Kingston, the wealthiest and the most prosperous negroes of the district migrated. In October, 1916, some of the first large groups left Mobile, Alabama, for the Northwest. The report says: "Two trainloads of negroes were sent over the Louisville and Nashville Railroad to work in the railroad yards and on the tracks in the West. Thousands more are expected to leave during the next month."

As soon as the exodus got well under way, Birmingham became one of the chief assembling points in the South for the migrants and was one of the chief stations on the way north. Thousands came from the flood and boll weevil districts to Birmingham. The records of the negro industrial insurance companies showed the effects of the migration both from and to Birmingham. The Atlanta Mutual Insurance Company lost 500 of its members and added 2,000. Its debit for November, 1916, was $502.25; for November, 1917, it was $740. The business of the Union Central Relief Association was greatly affected by the migration. The company in 1916 lost heavily. In 1917 it cleared some money.

The State of Mississippi, with a larger percentage of negroes than any other State in the Union, naturally lost a large number of its working population. There has been in progress [pg 65] for a number of years a movement from the hill counties of the State of Mississippi to the Delta, and from the Delta to Arkansas. The interstate migration has resulted from the land poverty of the hill country and from intimidation of the "poor whites" particularly in Amite, Lincoln, Franklin and Wilkinson counties. In 1908 when the floods and boll weevil worked such general havoc in the southwestern corner of the State, labor agents from the Delta went down and carried away thousands of families. It is estimated that more than 8,000 negroes left Adams county during the first two years of the boll weevil period. Census figures for 1910 show that the southwestern counties suffered a loss of 18,000 negroes. The migration of recent years to adjacent States has been principally to Arkansas.72

Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, seriously felt the migration. The majority of the "lower middle class" of negroes, twenty-five per cent of the business men and fully one-third of the professional men left the city—in all between 2,000 and 5,000. Two of the largest churches lost their pastors and about 200 of each of their memberships. Other churches suffered a decrease of forty per cent in their communicants. Two-thirds of the remaining families in Jackson are part families with relatives who have recently migrated to the North.

For years the negroes of Greenville have been unsettled and dissatisfied to the extent of leaving. Negroes came from Leland to Greenville to start for the North. This condition has obtained there ever since the World's Fair in Chicago, when families first learned to go to that section whenever opportunities for establishment were offered them. Although the negroes from Greenville are usually prosperous, during this exodus they have mortgaged their property or placed it in the hands of friends on leaving for the North. Statistics indicate [pg 66] that in the early part of the movement at least 1,000 left the immediate vicinity of Greenville and since that time others have continued to go in large numbers.73

Greenwood, with a population evenly balanced between the white and black, had passed through the unusual crisis of bad crops and the invasion of the boll weevil. The migration from this point, therefore, was at first a relief to the city rather than a loss. The negroes, in the beginning, therefore, moved into the Delta and out to Arkansas until the call for laborers in the North. The migration from this point to the North reached its height in the winter and spring of 1916 and 1917. The migrants would say that they were going to Memphis, but when you next heard from them they would be in Chicago, St. Louis or Detroit. The police at the Illinois Central depot had been handling men roughly. When they were rude to one, ten or twelve left. Young men usually left on night trains. Next day their friends would say, "Ten left last night," or, "Twelve left last night." In this manner the stream started. Friends would notify others of the time and place of special trains. The type of negro leaving is indicated in the decline in the church membership. Over 300 of those who left were actively connected with some church. During the summer of 1917, 100 houses [pg 67] stood vacant in the town and over 300 were abandoned in the McShein addition. As the crops were gathered people moved in from the country, from the southern part of the State and from the "hills" generally to take the places of those who had left for the North.

There was no concerted movement from Clarksdale, a town with a population of about 400 whites and 600 blacks; but families appeared to slip away because of the restlessness and uneasiness in evidence everywhere. From the rural district around there was considerable migration to Arkansas, but considerable numbers were influenced to leave for Buffalo and Chicago. Mound Bayou lost some of its population also to Arkansas and the North, as they could buy land cheaper in the former and find more lucrative employment in the latter. Natchez did not suffer a serious loss of population until the invasion of the boll weevil and the floods.

Hattiesburg, a large lumber center, was at the beginning of the exodus, almost depopulated. Some of the first migrants went to Pennsylvania but the larger number went to Chicago. It became a rallying point for many negroes who assembled there ostensibly to go to New Orleans, at which place they easily provided for their transportation to Chicago and other points in the North. From Laurel in Jones county, a large sawmill district, it is estimated that between 4,000 and 5,000 negroes moved north. About 3,000 left Meridian for Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit and Pittsburgh. Indianola, a town with a number of negro independent enterprises, also became upset by this movement, losing a considerable number of progressive families. Gulfport, a coast town a short distance from New Orleans, lost about one-third of its negro population. About 45 families left Bobo for Arkansas, and 15 families went to the North. Johnstown, Mississippi, lost 150 of its 400 negroes.74

The owners of turpentine industries and lumber plants in southeastern Mississippi were especially affected by the exodus. In Hinds, Copiah, Lincoln, Rankin, Newton and Lake counties, many white residents rather than suffer their crops to be lost, [pg 68] worked in the fields. It was reported that numbers of these whites were leaving for the Delta and for Kentucky, Tennessee and Arkansas. Firms there attempted to look in the North that they might send for the negroes whom they had previously employed, promising them an advance in wages.

At the same time the Illinois Central Railroad was carrying from New Orleans and other parts of Louisiana thousands into Indiana, Illinois and Michigan. At the Illinois Central Railroad station in that city, the agent had been having his hands full taking names of colored laborers wanting and waiting to go North. About the first of April, 1917, there came also the reports from New Orleans that 300 negro laborers left there on the Southern Pacific steamer for New York, and 500 more left later on another of the same company's steamships bound also for New York, it was said, to work for the company. Thousands thus left for the North and West and East, the number reaching over 1,200.

It is an interesting fact that this migration from the South followed the path marked out by the Underground Railroad of antebellum days. Negroes from the rural districts moved first to the nearest village or town, then to the city. On the plantations it was not regarded safe to arrange for transportation to the North through receiving and sending letters. On the other hand, in the towns and cities there was more security in meeting labor agents. The result of it was that cities like New Orleans, Birmingham, Jacksonville, Savannah and Memphis became concentration points. From these cities migrants were rerouted along the lines most in favor.

The principal difference between this course and the Underground Railroad was that in the later movement the southernmost States contributed the largest numbers. This perhaps is due in part to the selection of Florida and Georgia by the first concerns offering the inducement of free transportation, and at the same time it accounts for the very general and intimate knowledge of the movement by the people in States through which they were forced to pass. In Hattiesburg, Mississippi, for example, the first intimation of a great movement of negroes [pg 69] to the North came through reports that thousands of negroes were leaving Florida for the North. To the negroes of Florida, South Carolina, Virginia and Georgia the North means Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and New England. The route is more direct, and it is this section of the northern expanse of the United States that gets widest advertisement through tourists, and passengers and porters on the Atlantic coast steamers. The northern newspapers with the greatest circulation are from Pennsylvania and New York, and the New York colored weeklies are widely read. Reports from all of these south Atlantic States indicate that comparatively few persons ventured into the Northwest when a better known country lay before them.

The Pennsylvania Railroad, one of the first to import laborers in large numbers, reports that of the 12,000 persons brought to Pennsylvania over its road, all but 2,000 were from Florida and Georgia. The tendency was to continue along the first definite path. Each member of the vanguard controlled a small group of friends at home, if only the members of his immediate family. Letters sent back, representing that section of the North and giving directions concerning the route best known, easily influenced the next groups to join their friends rather than explore new fields. In fact, it is evident throughout the movement that the most congested points in the North when the migration reached its height, were those favorite cities to which the first group had gone.75 An intensive study of a group of 77 families from the South, selected at random in Chicago, showed but one family from Florida and no representation at all from North and South Carolina. A tabulation of figures and facts from 500 applications for work by the Chicago League on Urban Conditions among Negroes gives but a few persons from North Carolina, twelve from South Carolina and one from Virginia. The largest number, 102, came from Georgia. Applicants for work in New York from the south Atlantic States are overwhelming.76

For the east and west south central States, the Northwest was more accessible and better known. St. Louis and Cincinnati are the nearest northern cities to the South and excursions have frequently been run there from New Orleans, through the State of Mississippi. There are in St. Louis, as in other more northern cities, little communities of negroes from the different sections of the South. The mail order and clothing houses of Chicago have advertised this city throughout the South. The convenience of transportation makes the Northwest a popular destination for migrants from Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Texas and Tennessee. The Illinois Central Railroad runs directly to New Orleans through Tennessee and Mississippi.

There were other incidental factors which determined the course of the movement. Free trains from different sections broke new paths by overcoming the obstacles of funds for transportation. No questions were asked of the passengers, and, in some instances, as many as were disposed to leave were carried. When once they had advanced beyond the Mason and Dixon line, many fearing that fees for transportation would be deducted from subsequent pay, if they were in the employ of the parties who, as they understood, were advancing their fares, deserted the train at almost any point that looked attractive. Employment could be easily secured and at good wages. Many of these unexpected and premature destinations became the nucleuses for small colonies whose growth was stimulated and assisted by the United States postal service. (source: Negro Migration During The War)

I am Very Happy Read your Blog

ReplyDeleteI did not know about this read before your blog

Thank your

http://www.livestreamsportshd.com/

I am Very Happy Read your Blog

ReplyDeleteI did not know about this read before your blog

Thank your

http://gainmoneyfast.com/-94216.htm/

Thank you for sharing this. I appreciated the opportunity to read it.

ReplyDelete