David Dabydeen writes in Highbeam, "Bound in the chains of cash," a book review of The Trader, the Owner, the Slave, by James Walvin -- Stated simply, between c.1550 and 1860 slavery was integral to the way the Western world lived, functioned and prospered." If James Walvin is right (and a host of eminent scholars would agree), why have we in Britain today mostly forgotten this significant debt to Africans? Guilt? Shame? The fear of reparations? Or is it, as Salman Rushdie wrote, that the British don't know their history because most took place overseas?

Walvin, emeritus professor of history at the University of York, has done more to remind us of the links between slavery and British social and economic development than any other historian. An early pioneer of the study of the Black presence in Britain, he has published numerous articles and books on the central role that Britain played in the shipping of millions of Africans, and the benefits it received from the trade in sugar, tobacco, cotton, and other slave-produced commodities.

John Newton (1725-1807)

The Trader, the Owner, the Slave, published to mark the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the British slave trade, strives to give pulse and heartbeat to the vast data on slavery by telling the lives of three individuals, each enmeshed in the transatlantic trade. First is John Newton (1725-1807), the celebrated cleric, famous to this day for writing the hymn "Amazing Grace". As a boy, Newton was deeply pained when death removed his doting mother from him. To the end of his days he remembered his acute suffering because of separation from her love. Yet as a young man he set off on voyages, as a first mate and then as captain, trawling the coast of Africa for slaves, separating children from parents, husbands from wives.

It was a squalid business, as he was to reveal in 1788 when he was persuaded to join the Abolitionist cause. He published an essay denouncing the "unhappy and disgraceful branch of commerce". Disease, death, the flogging and execution of rebellious slaves, the raping of women aboard ship, fraud among the merchants: he had first-hand involvement in its impieties .

When he looked back, he confessed that "I never had a scruple at the time", and that he only gave up slaving because of ill-health. Why, then, did this great evangelical preacher, this civilised being (an avid collector of books who read the classics on his slaving voyages) engage in what he later deemed to be a crime against humanity? It was for the money, stupid. He was besotted with one Mary Catlett, but had to prove himself to her family as a man of means. He slaved for love, and got to marry her. African suffering paid for his wedding, his matrimonial home and his domestic bliss.

Secondly, there is Thomas Thistlewood (1721-1786), a cultured Lincolnshire man with limited prospects (the family of the woman he wanted to marry rejected him because he had insufficient money) who made his fortune by emigrating to Jamaica in 1750. He worked his way up the plantation system, eventually owning land and his own herd of slaves. Thistlewood kept a diary in which he recorded his thirst for reading (he maintained a library of more than 1,000 volumes) and for black flesh. In his 36 years in Jamaica he logged in his diary (in schoolboy Latin, "Pro. Temp. A Nocte. Sup Lect. Cum Marina") sexual intercourse with 138 African women and children.

He was liberal in his punishment of slaves. Fed a meagre diet, the slaves would eat the sugarcane, but when they were caught Thistlewood had them flogged, then had their wounded bodies rubbed in salt pickle, lime juice and bird pepper. He routinely ordered his slaves to urinate and defecate in each other's mouths.

One slave, however, Phibbah, caught his fancy and he showered her with gifts, falling in love with her. It was a relationship that lasted 30 years. Phibbah bore him a son and was, in all but name, his wife. She cared for him in his bouts of sickness and at his deathbed. In his will he released her from slavery and left her money to buy land. Thistlewood, like Newton, was steeped in human cruelty and romance.

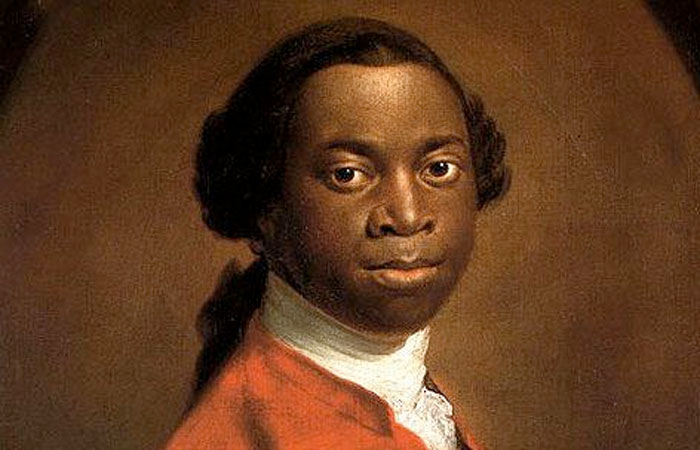

Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797)

Finally comes Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797), a slave who rose to international prominence when he published his autobiography in Britain in 1789. His book became an 18th-century bestseller: there were nine editions between 1789 and 1794, and it was translated into Dutch, German and Russian. Equiano was kidnapped as a boy by slave traders in Africa, removed from his family (the longing for his mother gives his narrative an exquisite poignancy), taken to England and then the West Indies and America, as a slave on ships engaged in the New World trade.

He learnt English, realizing that mastering the language could lead to liberation. Like Newton and Thistlewood he had a devotion to books, reading Homer, the Bible, Shakespeare, Milton, as well as newspapers, sermons, novels, travelogues and economic tracts. In 1767, after years of earning tiny sums by petty trading, he managed to accumulate £40 with which to buy his freedom. As a free man, he worked on ships trading in the Mediterranean and the Americas. In 1773, together with the 14-year-old Horatio Nelson, he was a sailor on the Phipps expedition to the North Pole.

Settling in England in 1777, he quickly made friends with writers, intellectuals, politicians and clergymen sympathetic to the plight of the African. He became a leading Abolitionist in Britain, traversing the land and reading to huge audiences.

After a life of deprivation and humiliation he found love, in 1792 marrying an Englishwoman from Soham, Susannah Cullen. He had family again, Susannah giving birth to two daughters. It was a short-lived happiness; Susannah died less than four years after their marriage, and one of the daughters the following year.

Walvin has told a remarkable and gripping story, asking profound questions about what makes beasts of men, and what can redeem them from their ghastly behaviour. Equiano's book, Walvin suggests, and the slave's abiding belief in the capacity for human decency, provide partial answers to such questions. (aouexw: Highbeam)

No comments:

Post a Comment