Melissa Harris-Perry

Between her popular column in the Nation, her show-stealing turns as a guest anchor on MSNBC and her willingness to jump into the digital fray, Melissa Harris-Perry is well on her way to being a household name.

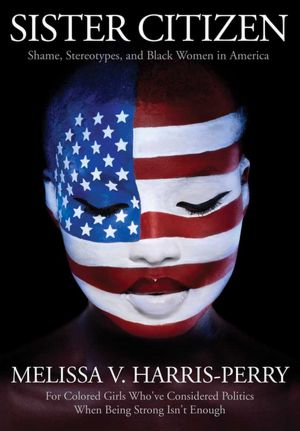

Her astonishing new work, "Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America," spans more than a century of history and several decades of pop culture along with an in-depth survey of political thought. (Amazingly, Harris-Perry achieves all of this without becoming mired in jargon or turgid citations.) "Sister Citizen" will find its place with ambitious undergraduates gathered around a seminar table as well as members of book clubs chatting over margaritas.

The crux of Harris-Perry's argument is that the prevailing stereotypes of black women profoundly affect the ways that black women are seen by America, but also the ways that they see themselves. This misrepresentation shapes and often limits black women's participation as American citizens. While scholars may find some of the ground covered here to be a bit familiar, "Sister Citizen" is written for the benefit of all Americans - sister citizens, brother citizens and anyone else who cares about the way this country works.

Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America; by Melissa Harris-Perry; (Yale University Press; 378 pages; $28)

"Sister Citizen" is difficult to classify, as it blends novel excerpts, poetry, focus-group transcripts, political analysis, tables, charts, photographs and a touch of speechifying. The title nod to Audre Lorde's audacious "Sister Outsider" lets us know that this is an author who is not afraid to have an opinion. The work's second subtitle, "For Colored Girls Who've Considered Politics When Being Strong Isn't Enough," isn't quite as raw as its inspiration, Ntozake Shange's groundbreaking choreopoem, "For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf."

But perhaps it is Harris-Perry's goal to write with cool intention. Defying classification, "Sister Citizen" relies on literature, but is not as personal as literature. It uses focus-group statistics, but it is more individuated than sociology. There is political theory here, but this is not a political science textbook. I am not sure that there is yet a name for this type of work that manages to be diffuse yet intently focused.

Harris-Perry's focus is on the lived experience of black women, but also the ways that black women are perceived by America. Her exploration of the images of black women in the wake of Hurricane Katrina is exhaustive and sometimes a little exhausting. In addition, she casts an unflinching eye at the Duke University lacrosse case, the R. Kelly trial and other hot-button subjects that will no doubt spark conversations around many a dinner table.

Melissa Harris-Perry

Perhaps because of the timing of the publication, there is a 500-pound pop-culture gorilla in the room that does not make it into the text: the blockbuster film "The Help." Harris-Perry's Twitter followers and viewers of MSNBC were witnesses to her outrage over the depiction of black women who worked as maids in the Jim Crow South. On television and in the twitterverse, she decried the lack of historical context in the feel-good film. She also argued that the way that black women see themselves was not truly addressed.

If this is the case, "Sister Citizen" serves as an antidote to "The Help." In her discussion of the Mammy stereotype, Harris-Perry provides a particularly astute analysis of why the enduring image is so offensive. Unlike the loud-mouthed Sapphire and promiscuous Jezebel, Mammy embodies many positive attributes - she is kind, nurturing and capable in the kitchen. Indeed, many of the women in Harris-Perry's study embrace these characteristics. What they reject is the idea that these traits that they so value about themselves are seen as benefits for families not their own.

In this terrain lies the irony of "Sister Citizen." Cited early on is Kate Rushin's "The Bridge Poem," in which the speaker laments the role of go-between. "I've got to explain myself/ To everybody/ I do more translating/ Than the Gawdamn U.N./ Forget it/ I'm sick of it."

Yet "Sister Citizen" engages in as much translation and explanation. This is hard work, and Harris-Perry is more than up to the task. As a black woman myself, I am repeatedly stopped by curious strangers who want to know if I loved "The Help" as much as they did. In the past, weary of explaining, I have avoided the conversation altogether. In the future, I will simply proffer my copy of "Sister Citizen." (source: San Francisco Gate)

No comments:

Post a Comment