Gregory J. Wallace, a New York lawyer, and the author of "Two Men Before the Storm: Arba Crane's Recollection of Dred Scott and the Supreme Court Case That Started the Civil War," writes in the Baltimore Sun on the 150th Anniversary of the Dred Scott Decision, on March 6, 2007, in an article entitled, "Wrong way to teach about Dred Scott":

Today is the 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court's infamous 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which paved the way for the Civil War. One elite New York City high school is requiring its advanced American history students to read the multiple opinions written by the Dred Scott justices. If there is a better way to keep students from learning what happened in the Dred Scott case, I can't think of one.

The ruling is an incomprehensible mess, a hodgepodge of pro-slave-state racist sentiment dressed up as legal opinion. Any student struggling to decipher Dred Scott by reading the case will miss the point. The case is not about the long-abolished law of slavery but the law of unintended consequences, which can never be repealed. And the best teaching aid is an obscure painting.

An illiterate St. Louis slave named Dred Scott sued his owner for his freedom. He won in state court, lost on appeal, filed a new case in federal court, lost again, and then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The case was argued twice in the Supreme Court in 1856, just as Americans had begun to debate slavery with more than words. In between the two arguments, warfare broke out in Kansas and an abolitionist was beaten nearly to death in the U.S. Senate.

On the court sat Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney of Maryland. He had owned slaves but freed them. As a young lawyer, he had successfully defended an abolitionist minister accused of inciting a slave insurrection. As a justice, he had voted to free the Amistad slaves. But by the time the Dred Scott case reached the court, in the words of a historian, the 80-year-old chief justice was "a bitter sectionalist, seething with anger at Northern insult and Northern aggression."

And so, on March 6, 1857, before a country that was a tinderbox, the court struck a match. In a harsh, racially driven majority opinion written by Chief Justice Taney, the court rejected Dred Scott's claim for freedom, holding that blacks in bondage were property without rights and Congress had no power to halt the spread of slavery. Chief Justice Taney intended to end the slavery controversy forever by resolving every slavery issue in favor of the South. Instead, his opinion, which effectively nationalized slavery, made sectional compromise impossible and hurled the country toward the abyss. A wave of Northern outrage descended on Chief Justice Taney, while the South warned that unless the North accepted the opinion, there would be disunion.

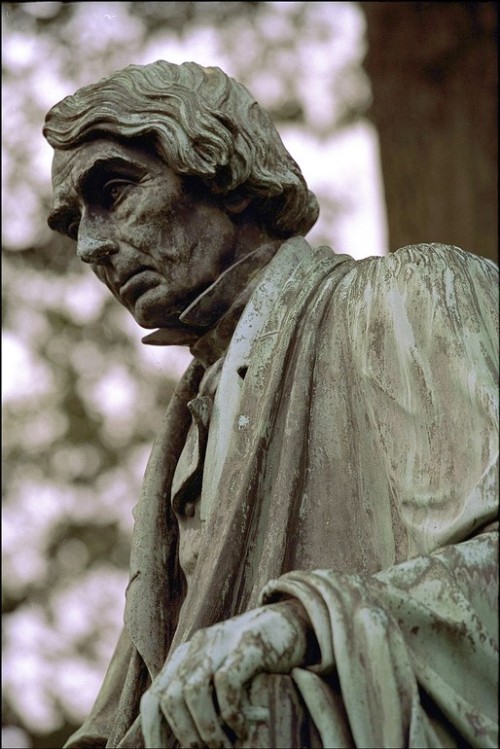

The law of unintended consequences ruled the day - something the chief justice came bitterly to understand. Not long before the Civil War began, he sat for a portrait by Emanuel Leutze. He is seated in a red chair, his left hand resting on a pad of paper while his right hand hangs lifelessly against the right arm of the chair. In his eyes is an expression of profound melancholy, the look of a man who had seen into the ruinous future that he had wrought but had not intended and could never undo. During the Civil War, a Washington diarist described him as the "saddest" figure in the city.

It took the deaths of 600,000 American soldiers to reverse Chief Justice Taney's decision.

Another unintended consequence was that the press, aroused by the ruling, discovered the whereabouts of Irene Emerson, the St. Louis widow who had owned Dred Scott. After fighting Mr. Scott's lawsuit in the state courts, she had left St. Louis, moved to Massachusetts, and then remarried - to an abolitionist congressman. Another round of Northern anger forced the congressman and his wife to free the Scott family. Dred Scott, whose children reappeared in St. Louis, had won his and his family's freedom after all.

So, the Dred Scott opinion ultimately freed all of the slaves, including Dred Scott - the opposite of what Chief Justice Taney intended.

The Dred Scott case stands for a timeless truth that resonates today. The powerful are not gods; they can never know the consequences of using enormous powers, and they must use such powers with humility.

The best way I know to teach students how the law of unintended consequences brought about the greatest catastrophe in American history is not to assign the Dred Scott case as reading, but to show them that painting. (source: Gregory J. Wallance, Baltimore Sun )

This is really good

ReplyDeleteThanks for your Post

http://www.livestreamsportshd.com/

Thanks for your good and reliable post

ReplyDeletehttp://gainmoneyfast.com/-94216.htm/