From Law & Politics "Justice Denied," by Jack Hamann.

I lied.

Well, to be fair, I perpetuated a lie. But it was a lie just the same.

And now that the truth is out, I wish I’d uncovered it earlier.

It started with a lynching. In Seattle.

Italian Army Pvt. Guglielmo Olivotto

The victim was a skinny, shy 32-year-old Italian Army private named Guglielmo Olivotto.

His death was reported by a skinny, not-so-shy American Army private named Clyde Lomax.

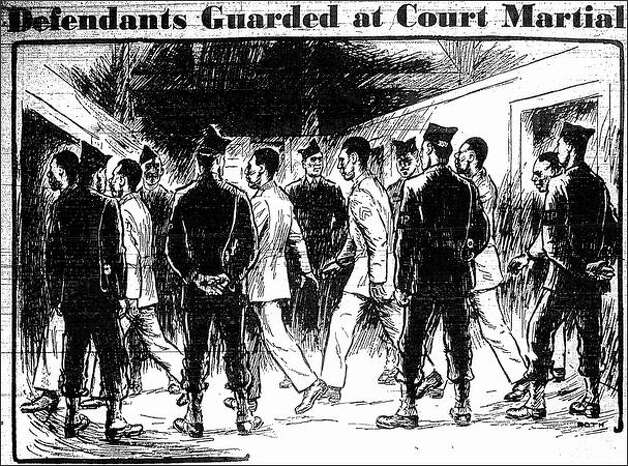

Lomax, who was white, would later testify against 43 fellow soldiers, all of them black. The murder trial would become a worldwide sensation, the largest and longest U.S. Army court-martial of World War II. Lomax’s testimony came at the behest of an ambitious young Army prosecutor named Leon Jaworski.

Leon Jaworski

Yes, that Leon Jaworski: powerhouse Houston corporate attorney, Lyndon Johnson protégé, Warren Commission counsel, American Bar Association president (1971-’72). The same Leon Jaworski who rocked the nation in 1974 when, as Watergate special prosecutor, he persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to order Richard Nixon to surrender secretly taped conversations. Jaworski made his first big splash in Seattle, where he took on a prosecution he considered, at the time, “the biggest case I ever tackled.” And yet, that case somehow slipped beneath the surface of American history, only to resurface decades later, tarnishing Jaworski’s otherwise stellar reputation and leading to a rare admission of fault by the Pentagon.

The death of Pvt. Olivotto on Aug. 14, 1944 was a national embarrassment. Throughout human history, most POWs in most wars had been treated as little better than slaves, if not worse. But during the decade prior to World War II, America led the charge for what came to be known as the Geneva Conventions on the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Signatories promised that war prisoners would be treated like human beings.

Olivotto was among tens of thousands of Italians captured in North Africa in 1943, initially assigned to a POW camp in Arizona before being transferred to Seattle. Letters written to loved ones by those in his unit offer a glimpse of America’s commitment to prisoner dignity:

“My Darling: I have never been as well-off as I am now … The treatment we get in this camp is excellent … Love, Armando.”

“Giovanna: I can assure you that the treatment given us by the Americans could not be bettered. The meals are excellent … the sleeping quarters are, without exaggeration, heavenly. Yours, Vincenzo.”

So, when Fort Lawton lynching headlines circled the globe, the War Department, State Department and White House squirmed. Not only did the crime violate the Geneva Conventions, but postwar prosecutions of Germans for mistreatment of Allied POWs were already on the drawing board. Unless justice was done in Seattle, the world might question whether Nazi trials were hypocritical.

Jaworski, it turned out, was lusting for a German war-crimes assignment. “In wartime, where you serve is nearly as important as how,” he later wrote.

“There were historic cases coming in Europe,” he observed. “I wanted in on them.” He fully understood that securing convictions in the Fort Lawton case was a necessary prerequisite.

Jaworski demanded complete control of both the criminal investigation and the courtroom prosecution. For more than two months, he and his investigators grilled suspects and potential witnesses; more than one suspect complained about coercion and intimidation, including threats to lynch uncooperative African-American soldiers. Evidence went missing, questionable accusers were granted immunity and contradictory evidence was ignored.

The slipshod detective work was confirmed in a scathing report to the Army’s inspector general. Stung by negative publicity about the lynching, the Pentagon had assigned Gen. Elliott Cooke to figure out whose head should roll. Working independently, Cooke interviewed everyone with possible knowledge of the crime. Defendant Willie Prevost swore that one of Jaworski’s interrogators “said I would know more about the case when that rope was around my damn neck.” Jaworski’s chief investigator, Robert Manchester, was forced to admit that “no part [of the investigation] was handled correctly.” In a blistering secret report submitted just two weeks before the trial, Cooke described the Army’s investigation as “reprehensible,” and recommended that several Fort Lawton officers be disciplined. He even insisted that fort Commander Harry Branson be relieved of his post (which he was).

Undeterred, Jaworski forged ahead. The night of the lynching, dozens of black soldiers had clashed with a company of Italian POWs; many were injured. On October 27, 1944, Jaworski charged 43 African-American soldiers with rioting, a crime carrying a penalty of up to life in prison. He also charged three of them with the first-degree murder of Olivotto. The motivation, Jaworski contended, was resentment and envy: black soldiers were allegedly upset about their second-class status in the still-segregated Army, even more so since Italian POWs seemed to be treated as well as or better than black GIs. Their supposed solution? Beat up Italians and string up one of them with a noose.

All 43 defendants were forced to share two lawyers, who were given just 10 days to prepare. Fortunately, the assigned counsel were no slouches: years later, William Beeks would become a long-serving federal judge, and Howard Noyd would go on to a distinguished corporate counsel career. Both men considered their central task to be saving the three murder defendants from the gallows.

The trial began in November 1944 and lasted five weeks, including Saturdays and Thanksgiving Day. Jaworski and Beeks tore into each other from the start. The transcript takes up five fat volumes, and contains the kind of drama that makes you wish you’d been seated in that courtroom:

Beeks: I object to counsel leading the witness. He has already denied—

Jaworski (interrupting): I thought you were interested in it.

Beeks: I am interested in your proceeding in a proper manner. You know the way as well as I do to proceed in these cases.

Jaworski: Now, if it please the court, I don’t propose to take a lecture from counsel as to whether I proceed correctly or not. If he has an objection to make, I suggest he make it to the court.

Judge Gerald O’Connor: I think in the future you should address your remarks to the court, Major.

Beeks: I should be glad to do that, but I submit the first off-the-record remark was made by counsel.

But the real theatrics were yet to come. During one tense cross-examination, Beeks noticed Jaworski referring to notes that looked out of place. In an epiphany, Beeks realized Jaworski had somehow gained possession of Cooke’s supposedly secret report. Although Beeks had no idea what the report contained, he knew that prosecutors were unequivocally required to share potentially exculpatory evidence with the defense. The defense attorney exploded.

Beeks: There are several occasions when I have asked for these reports, and it has been told to me they were so confidential and highly secret that [Colonel Jaworski] has not even been allowed to see it!

Jaworski, panicked that disclosure of Cooke’s report would likely blow his prosecution to pieces, offered a bellicose, improbable explanation.

Jaworski: We are not in the same situation. I am a government agent and you are not, and I have access and am supposed to know things that you are not.

That isn’t true now. It wasn’t true in 1944, either. But Jaworski proclaimed it with such conviction that the court bought it. The contents of the Cooke report remained hidden from public view until my wife, Leslie, and I extracted it from the National Archives six decades later.

Issuing verdicts that seemed almost predetermined, the all-white, all-officer panel of nine judges convicted 28 soldiers, stripping all but one of honorable discharges and sentencing them to prison terms ranging from six months to 25 years. Shortly after the trial, Jaworski received the assignment he had so dearly wanted, to prosecute the first war-crimes case in Germany.

In 1986, I began my first extensive reporting about the Fort Lawton case. Although I spent months on research, I lacked the time, money and experience to do a thorough job. Relying mostly on 1944 newspaper clippings, I produced an hourlong KING-TV documentary essentially repeating Jaworski’s version of events. I knew nothing about Cooke’s report.

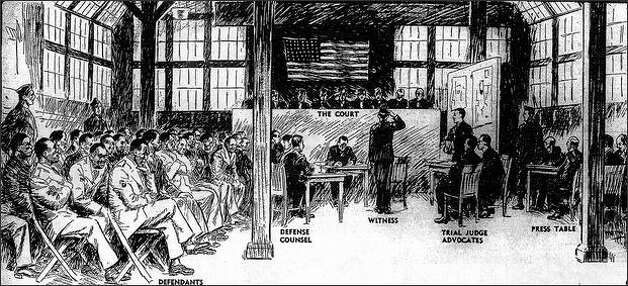

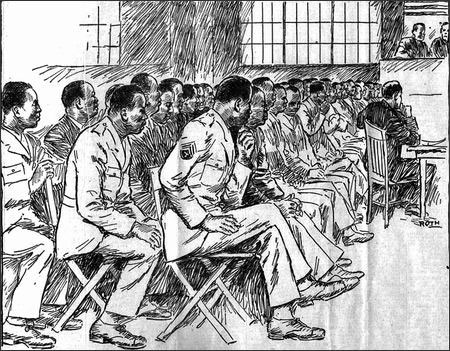

This 1944 newspaper sketch shows the soldiers on trial -- the only time in US history a group of black men were tried for lynching a white man. [Agencies]

Everything changed in 2003. For years, friends had been asking, “Doesn’t that Fort Lawton case strike you as strange? I mean, black people convicted of a lynching? In the Northwest?” My wife and I figured it was time to take a closer look. Older and surely wiser, we understood that we’d need to venture far beyond secondary sources such as newspapers, and focus on primary sources sequestered in libraries, museums and archives. Many months later, we landed at the National Archives, where—after many false starts—we unearthed Cooke’s report. It was, as you might imagine, the smoking gun.

Newly armed with thousands of pages of previously classified documents, we saw a different explanation begin to emerge. Blacks, it turned out, rarely complained about humane treatment of Italian prisoners; white soldiers and civilians were far more upset. Many had lost friends or loved ones in the North African campaign, in battles fought almost exclusively by white soldiers in Uncle Sam’s segregated Army. White veterans increasingly complained that enemy soldiers were being “mollycoddled” in U.S. custody.

When Italy surrendered in 1943, its captured soldiers were still treated as POWs, since much of Italy was still occupied by Germans. But prisoners were allowed additional liberties, including the opportunity to attend USO dances and otherwise fraternize with civilian women. More than a few American females were swept off their feet by Italian charm, brewing backlash in pockets of the white community. At Fort Lawton itself, fistfights broke out between POWs and white GIs on the three consecutive nights leading up to the August 14 riot, an undeniably germane fact that Jaworski convinced the court to exclude as irrelevant.

Newly armed with thousands of pages of previously classified documents, we saw a different explanation begin to emerge. Blacks, it turned out, rarely complained about humane treatment of Italian prisoners; white soldiers and civilians were far more upset. Many had lost friends or loved ones in the North African campaign, in battles fought almost exclusively by white soldiers in Uncle Sam’s segregated Army. White veterans increasingly complained that enemy soldiers were being “mollycoddled” in U.S. custody.

When Italy surrendered in 1943, its captured soldiers were still treated as POWs, since much of Italy was still occupied by Germans. But prisoners were allowed additional liberties, including the opportunity to attend USO dances and otherwise fraternize with civilian women. More than a few American females were swept off their feet by Italian charm, brewing backlash in pockets of the white community. At Fort Lawton itself, fistfights broke out between POWs and white GIs on the three consecutive nights leading up to the August 14 riot, an undeniably germane fact that Jaworski convinced the court to exclude as irrelevant.

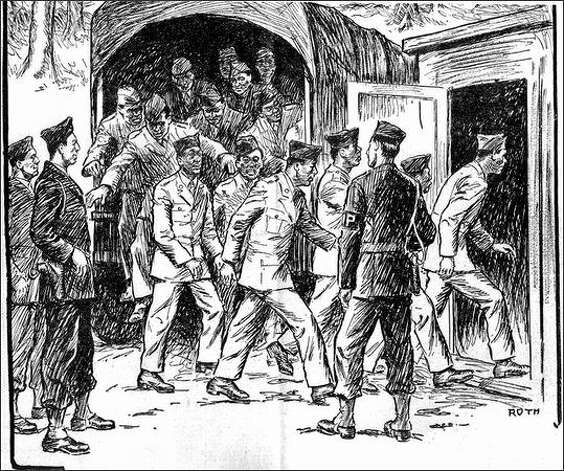

Published Nov. 25, 1944: The pen of Henry Roth, Post-Intelligencer staff artist, portrays two scenes at the general court-martial of 42 Negro soldiers charged with rioting at Fort Lawton last August. Left, three of the military guards stationed in the court room. Right, Pvt. Thomas Battle, a Negro soldier, taps the head of a defendant who he says was one of the rioters who stormed the barracks of former Italian prisoners of war. Photo: Seattle Post-Intelligencer / SL

The newly exhumed evidence made it clear that Clyde Lomax, the white soldier who claimed he “discovered” Olivotto’s body, was the most likely suspect. The night before, Lomax had been the soldier most responsible for escalating a small drunken fistfight into a full-fledged riot. Cooke called Lomax a “coward,” for lying about his whereabouts, and had him court-martialed and convicted of deserting his post during the very hour Olivotto was lynched. But since Jaworski managed to keep the report secret, he felt free to call Lomax as a witness against the black defendants.

After the 2005 publication of my book, On American Soil: How Justice Became a Casualty of World War II, members of Congress, and then the Pentagon, agreed to reopen the case. After a 15-month review, the Army’s highest court unanimously concluded that Jaworski had committed “egregious error.” On October 26, 2007, the court reversed the 1944 verdicts, reinstated honorable discharges, and ordered that all defendants—or their estates—be given the back pay and benefits they were denied while in prison. On October 14, 2008, President George W. Bush signed legislation authorizing the Army to add compound interest.

Although it seems to be a happy ending, there are lessons and regrets. During the nearly two decades between my initial reports and the publication of the book, many defendants passed away, never able to share the vindication with their families. Clyde Lomax also died during that interim; since there is no statute of limitations for murder, many have told me they would have liked to see him stand trial for Olivotto’s death.

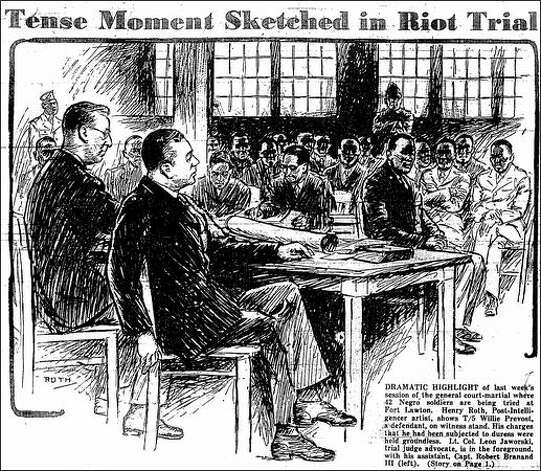

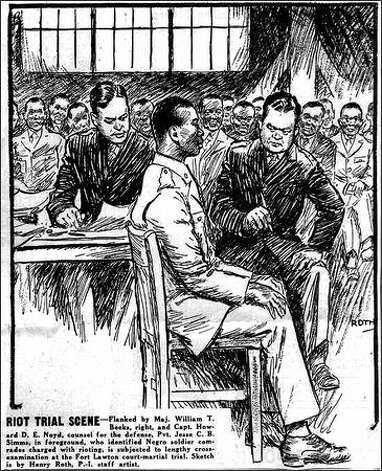

Published Nov. 23, 1944: Flanked by Maj. William T. Beeks, right, and Capt. Howard D.E. Noyd, counsel for the defense, Pvt. Jesse C. B. Simms, in foreground, who identified Negro soldier comrades charged with rioting, is subjected to lengthy cross-examination at the Fort Lawton court-martial trial. Sketch is by Henry Roth, P.-I. staff artist. Photo: Seattle Post-Intelligencer / SL

I most regret my initial reliance upon the 1944 newspaper clippings. I had not stopped to consider that reporters of that era were almost exclusively white, male and middle class, or that they were often much too chummy with military officials, or that the Army had wide powers to censor wartime reporting. Their stories, in retrospect, were full of holes and unanswered questions.

On the other hand, On American Soil was published just as the American public was learning about treatment of enemy soldiers at Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo Bay. The fact that Americans once spent extraordinary resources seeking justice for the death of a single POW stood in stark contrast to the more recent rather casual disregard of Geneva Conventions commitments. If we look at our reflection through the mirror of Fort Lawton, we might wonder where our values and idealism have gone.

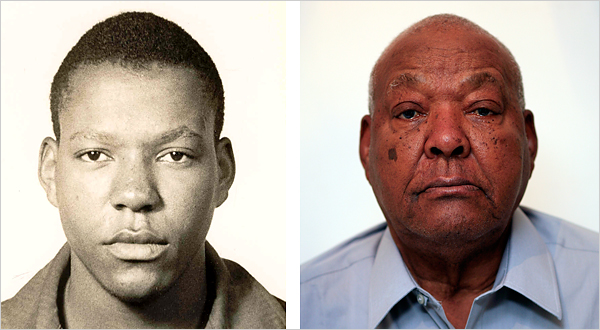

Pvt. Samuel Snow in his booking photograph on charges in 1944 and Mr. Snow in his home in Leesburg, Florida.

Last summer, 84-year-old defendant Samuel Snow, accompanied by his family, traveled from his Florida home to participate in three days of Seattle-area tributes. On the third day, with family members of several now-deceased defendants in the audience, Assistant Army Secretary Ronald James stood outside the Fort Lawton chapel and presented long-overdue honorable discharges. “I grieve for an Army that failed to honor its own values at Fort Lawton,” he said. To the widows and family members, he said, “The Army is genuinely sorry. I am sorry. Sorry for your husbands, loved ones, fathers and grandfathers, for the lost years of their lives.”

Snow was not at the chapel that morning. Overwhelmed by an outpouring of accolades and support, his pacemaker began firing on all cylinders. At the hospital later that day, his family handed him his honorable discharge, and watched with joy as he clutched it to his chest and grinned. Hours later, he was dead, his son and daughter-in-law at his side.

Snow’s family believes his heart had been beating on borrowed time. They are convinced he willed himself to carry on long enough to witness the day his loved ones could see his good name cleared. They are sure he died a happy man.

I don’t doubt that one bit. I only wish the other Fort Lawton defendants could have known the same sense of closure before their own times expired. L&P

Jack Hamann is the award-winning author of On American Soil: How Justice Became a Casualty of World War II. For more about the Fort Lawton case, visit www.jackhamann.com. (Read more: http://www.seattlepi.com/local/article/The-almost-forgotten-Seattle-story-that-may-2115203.php#ixzz1js5RjY18)

and ... the execution of Emmett Till's father in France, following WWII. Does anyone have information to share on those trials?

ReplyDeleteHow was Jaworski involved in the trial that ended with Louis Till's hanging in France? I am seeking military records from that event.

ReplyDeleteOkay, now you're playing "stump the band." Honestly, I'm unaware of either Louis Till's hanging, or Jaworski's involvement. I'll do some research, but I'm clueless.

DeleteThis was just an interesting and compelling story. The historic actors involved, the cover-up, the court marshal, the trial are something out of a fiction novel. But, history certainly turns out to be far more interesting than fiction.

Thanks for reading and commenting. The Louis Till thing needs further research.

--Ron Edwards, US Slave Blog

I just came across this; sorry for being three years late to the party!

ReplyDeleteJaworski, as best I can tell, had •nothing• to do with Louis Till’s court martial. Apart from the Fort Lawton case, in (and after) WWII Jaworski was the prosecutor at the Johannes Kunze murder trial in Oklahoma (earlier in 1944), where five German prisoners of war were accused of beating to death a fellow prisoner for passing information to the U.S. authorities; and after the war, in July and August 1945, he prosecuted the Rüsselsheim massacre case in Germany, against eleven German civilians accused of murdering six American airmen forced down over Germany.

Louis Till is buried in northern France — but he was accused of the rape of two Italian women, and the murder of another, in the town of Civitavecchia in central •Italy•. He was tried in Italy, and hanged on 2 July 1945 near Pisa — again, •not• France. It seems unlikely Jaworski was involved in the Till court martial, for several reasons.

First, it appears that the Till prosecution must have taken place not long before the Rüsselsheim trial began; the case in Germany was important, and the time required for the investigation of it and preparation for the trial probably would not have allowed Jaworski to participate in the Till court martial.

Second, by the time he got to Europe, in Jan. 1945, Jaworski was a high-level military prosecutor, assigned to investigate and prosecute •war• crimes. A charge like the Rüsselsheim case — a high profile, politically important war crimes matter — was far more consistent with his status in the military justice hierarchy, than was an assignment such as the Till case. Although Till’s was a capital case, it was garden-variety criminal conduct, not a war crime. As such, the Till investigation and court martial was comparatively run-of-the-mill.

Third, it seems that the Rüsselsheim case was Jaworski’s first trial assignment in Europe.

And fourth, I’ve seen nothing that suggests Jaworski was assigned to any cases in Europe •outside• of Germany. Among other things, he was born in Waco, Texas, but he was the son of Polish and Austrian immigrant parents, and spoke only German until he started school, so he had fluent language skills that were useful for assignments in Germany.

The hand of military justice appears to have been applied particularly heavily against black soldiers in the WWII era. I know almost nothing of the specific case against Louis Till, but that general historical fact has to give one reservations about whether Till truly met a just fate. Nevertheless, there seems to be nothing to suggest that Leon Jaworski had anything whatsoever to do with Till’s case — and the question, “how was Jaworski involved in [it]?,” seems almost random! To describe that question as coming out of left field would be a •generous• assessment.

I just came across this; sorry for being three years late to the party!

ReplyDeleteJaworski, as best I can tell, had •nothing• to do with Louis Till’s court martial. Apart from the Fort Lawton case, in (and after) WWII Jaworski was the prosecutor at the Johannes Kunze murder trial in Oklahoma (earlier in 1944), where five German prisoners of war were accused of beating to death a fellow prisoner for passing information to the U.S. authorities; and after the war, in July and August 1945, he prosecuted the Rüsselsheim massacre case in Germany, against eleven German civilians accused of murdering six American airmen forced down over Germany.

Louis Till is buried in northern France — but he was accused of the rape of two Italian women, and the murder of another, in the town of Civitavecchia in central •Italy•. He was tried in Italy, and hanged on 2 July 1945 near Pisa — again, •not• France. It seems unlikely Jaworski was involved in the Till court martial, for several reasons.

First, it appears that the Till prosecution must have taken place not long before the Rüsselsheim trial began; the case in Germany was important, and the time required for the investigation of it and preparation for the trial probably would not have allowed Jaworski to participate in the Till court martial.

Second, by the time he got to Europe, in Jan. 1945, Jaworski was a high-level military prosecutor, assigned to investigate and prosecute •war• crimes. A charge like the Rüsselsheim case — a high profile, politically important war crimes matter — was far more consistent with his status in the military justice hierarchy, than was an assignment such as the Till case. Although Till’s was a capital case, it was garden-variety criminal conduct, not a war crime. As such, the Till investigation and court martial was comparatively run-of-the-mill.

Third, it seems that the Rüsselsheim case was Jaworski’s first trial assignment in Europe.

And fourth, I’ve seen nothing that suggests Jaworski was assigned to any cases in Europe •outside• of Germany. Among other things, he was born in Waco, Texas, but he was the son of Polish and Austrian immigrant parents, and spoke only German until he started school, so he had fluent language skills that were useful for assignments in Germany.

The hand of military justice appears to have been applied particularly heavily against black soldiers in the WWII era. I know almost nothing of the specific case against Louis Till, but that general historical fact has to give one reservations about whether Till truly met a just fate. Nevertheless, there seems to be nothing to suggest that Leon Jaworski had anything whatsoever to do with Till’s case — and the question, “how was Jaworski involved in [it]?,” seems almost random! To describe that question as coming out of left field would be a •generous• assessment.