Anti-busing protest in Boston, 1976

Nothing Changes

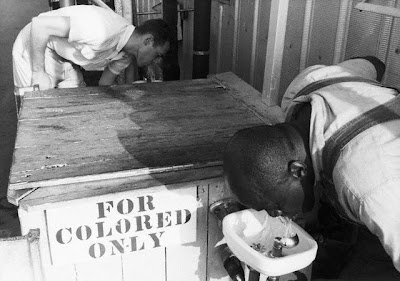

Peter Irons begins Jim Crow's Children with voices from the past. Drawing from WPA interviews, he quotes former slaves talking about difficulties they faced trying to read. "If we told [Mr. Tabb] we had been learnin' to read," recounts one slave, "he would near beat the daylights out of us" (p. 1). According to Irons, little has changed. African Americans still confront serious barriers to acquiring equal education in the United States.

In a sweeping work that traces black education from slavery to the present, Irons, who teaches at [***], suggests that Brown v. Board of Education,[1] the landmark Supreme Court ruling calling for the desegregation of public schools in the South, failed blacks. Although instrumental in dismantling federal approval of de jure segregation, or Jim Crow, in the South, Brown failed to deliver equal education to African American youth, a goal that continues to prove elusive, even today.

Much like James Patterson's Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and its Troubled Legacy,[2] Irons summarizes an ever increasing body of secondary literature on school segregation, adding weight to ascendant views that Brown did not end America's struggle with segregated education. In pursuing this goal, Irons provides a detailed summary of educational policy towards blacks beginning as early as slavery. He does an excellent job of showing, for example, that the South was never much of an outlier in either its racial views or racial practice, despite the absence of formal Jim Crow segregation in the North. Irons also does a deft job of summarizing the NAACP's strategy leading up to Brown, a story familiar to fans of Richard Kluger's classic work, Simple Justice.[3]

The full weight of Irons's book, however, does not come to bear until the second half. Dedicating six chapters to the reaction and results of the Supreme Court's ruling, Irons shows first how southern and later northern and western whites opposed forced integration. He documents white flight, busing controversies, and even terrorism in cities like Cleveland (which boasted large black populations and extreme white resistance). In his closing chapters, Irons picks through the ruins of desegregation, even interviewing black students and former plaintiffs in Brown, revealing that Jim Crow's spirit, if not his body, lives on.

The culprit, according to Irons, is the federal judiciary, and in particular the Supreme Court. If it weren't for the Burger and Rehnquist Courts, he contends, integration would have continued. The courts proved effective in the early stages of integration, first by forcing the South to submit to federal mandates, and later by imposing busing on the rest of the nation--only to concede ground in the 1970s and 80s by removing busing mandates and tolerating white flight out of heavily black districts.

Irons's argument is, undoubtedly, right. If the Supreme Court had continued to aggressively back desegregation, Jim Crow would have suffered. But, this is not the only reason to read Jim Crow's Children. In fact, Irons's work raises questions that are, in certain ways, even more interesting still. Irons shows that American whites, contrary to their oft-professed liberal proclamations about racial equality, proved reluctant to sacrifice what they perceived to be the future of their children for an abstract social ideal. And the Supreme Court, as much symbolic authority as it may possess, has been unwilling and (perhaps more important) unable to force Americans, over long periods of time, to do things they do not want to do. Herein lurks the most interesting part of Irons's study. He shows effectively not just that courts refused to back desegregation, but that white America refused to back desegregation. In pushing aggressively for the abstract goal of integration, Irons shows how the courts, through busing and other plans, destroyed American cities by driving white taxpayers from them, eroded faith in the courts as a means of protecting white interests, and drove a wedge between liberal left-wing elites and the white working class, thereby setting the stage for the impressive consolidation of power across class lines that we see in today's Republican Party.

Jim Crow's children then, are not just African American youths who may have been better off under equalization programs, but Republican crusaders like Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and William Rehnquist who rose to power expressly to dismantle what the Warren Court had wrought. Brown created both a myth and a monster.

Why? That is the subject of another study. And yet, racism, although an obvious culprit, may not be the only force at work here. On the contrary, an even deeper force, long at work within America's social formation, is likely also to blame. That is the utility of segregated education to the preservation of class.

When confronting the prospect of having their children bused into inner cities, white Americans did not have to be racist to realize that their children would suffer. It may be true, for example, that integration among children of the same class is a positive good. But, it may also be true that integration of children from different classes may prove, and will likely prove, the opposite. This is not because black children are different racially, but rather because Jim Crow involves much more than simply racial separation.

Segregation in America, whether de jure or de facto, has always been about resources just as much as about race. The idea behind segregation, initially, was not simply to punish blacks, but to create an underclass that was limited in terms of what it could accomplish, and thereby better suited for the menial tasks assigned to it. There was a reason, in other words, that Mr. Tabb would have beaten his slaves. If they had learned to read, they would have been less suited to being slaves.

Although slavery is gone, class structure continues in America, as in most societies. In this respect, centuries of segregated schooling have served their purpose--namely, the perpetuation of a class system in which African Americans inhabit the bottom caste, performing menial tasks with limited hope of advancement. The prospect confronting white parents with forced busing then, was to suddenly have their children relegated to the same lower class, not simply by association with black students, but being sent to underfunded, poorly equipped schools with student bodies who lacked the appropriate cultural, not to mention financial, capital.

If Irons had pursued this angle of analysis, he may have been less harsh on the Supreme Court. After all, Brown itself was an ambitious move--one that most white Americans agreed with only insofar as it did not affect them personally. In fact, like the due process revolution for criminal rights initiated by the Warren Court, Brown was a radical step against the grain of American popular opinion, one that invited the very backlash it received.

History, for better or for worse, is rarely determined by a few old men, even if they are Supreme Court Justices. On the contrary, larger forces play into the reasons why Supreme Court justices rule the way that they do. Haunting the Warren Court, for example, was the Cold War. Irons doesn't consider this in his analysis, and yet scholars like Mary Dudziak have shown its effect.[4] In fact, if Irons had considered Dudziak's work, his conclusions would only have been stronger. After all, once the Cold War ended, there was little compelling reason to promote equal education, save perhaps abstract moral ideals. Like it or not, these have never governed educational, or any other policy, in the United States. (source: History Net)

Peter Irons: Jim Crow's Children

No comments:

Post a Comment