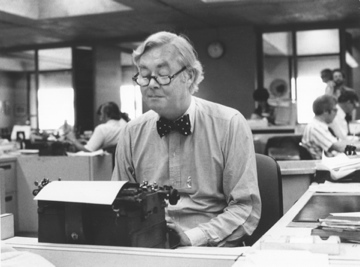

Daniel P. Moynihan

On February 9, 1967, the New York Times reported, "Lost Opportunity For Rights Cited," by Thomas A. Johnson: Daniel P. Moynihan, author of a controversial report on the Negro family, said in an article published yesterday that an opportunity to make a "total commitment to the cause of Negro equality" was lost 28 months ago because of the short-sightedness of civil rights leaders, Negro and white.

The article in the February issue of Commentary magazine says the nation was ready in June, 1965, to make this commitment after President Johnson, in a speech to the graduating class of Howard University in Washington, made a strong appeal for genuine equality for the Negro.

Mr. Moynihan called the speech "a bold beginning." But he said that before "half a year had passed the initiative was in ruins, and after a year and a half it is settled that nothing whatever came of it."

In the speech, Mr. Johnson called a White House conference, "To Fulfill These Rights." Mr. Moynihan, a former Assistant Secretary of Labor participated at both a planning conference at the White House in November, 1965, and the full-scale conference in June, 1966.

Daniel P. Moynihan

Widespread Objections-- At about the time of the President's speech, Mr. Moynihan wrote in Commentary, his report was published although it was intended to be an internal Labor Department document. It elicited widespread Negro objections for its contention that Negro families were becoming increasingly matriarchical and that family life among Negroes was disintegrating.

Although the report was first issued in 100 copies, it was later published by the Government Printing Office in the fall of 1965.

The report said 300 years of slavery and injustice had resulted in a "tangle of pathology" that would require a unified national effort to correct. Some Negro objections to the report, Mr. Moynihan said, actually put the blame on the Negroes for problems afflicting the race.

Negro objections to the report, Mr. Moynihan wrote in the Commentary article, contributed to the failure of the White House conference.

He [Moynihan] wrote: "This time the opposition emanated from the supposed proponents of such a commitment: from Negro leaders unable to comprehend their opportunity; from civil rights militants, Negro and white, caught up in a frenzy of arrogance and nihilism; and from white liberals unwilling to expend a jot of prestige to do a difficult but dangerous job that had to be done, and could have been done. But was not."

Furor Over Report--Mr. Moynihan stresses in the article that the furor over his report contributed to the failure to take advantage of the opportunity to win national support.

The reasons Mr. Moynihan cited for his belief that the nation was ready to follow Mr. Johnson's lead were that he had been "overwhelmingly elected the preceding fall and given the largest majorities in the House and Senate since those of the early Congresses that enacted the New Deal" and that the speech followed years of civil rights demonstrations in the South that were "unassailable in their justice."

The author was pessimistic about immediate progress for Negro aspirations in the United States because of the white backlash.

"It appears," he wrote, "that the nation may be in the process of reproducing the tragic events of the Reconstruction: giving to Negroes the forms of legal equality, but withholding the economic and political resources which are the bases of social equality."

He noted that white Americans generally feel that Negroes "have received enough for the time being."

Mr. Moynihan, 39 years old, is director of the John Center for Urban Studies of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

A Commentary official said the article was Mr. Moynihan's first public statement on the controversy that began in 1965. The official said Commentary is an independent magazine of thought and opinion that is published as a public service by the American Jewish Committee.

Mr. Moynihan said yesterday in a telephone interview that he had written the Commentary article because he felt advocates of civil rights should face up to the truth that "we missed a golden opportunity but that we can't give up.

"We must retrench to do the job right," he added.(source: New York Times)Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan on Race (1967)

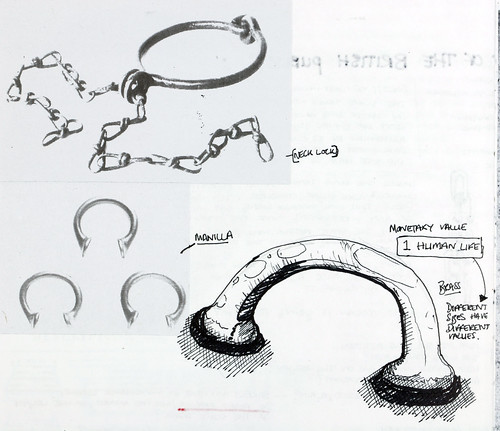

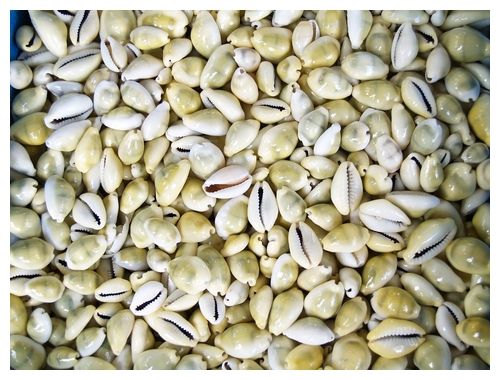

Do these heavy Schetz manillas even exist today, and if so, what do they look like? Duchateau, Royal Art of Benin, shows a plaque with a European holding two pieces with barely flared ends whose apparent size could match these specifications, while p.15 ilustrates five pieces of conventional form, but without scale. Then, too, the Dutch participated in the trade. Did they get their manillas from nearby Antweerp as well, or did they use something different.

Do these heavy Schetz manillas even exist today, and if so, what do they look like? Duchateau, Royal Art of Benin, shows a plaque with a European holding two pieces with barely flared ends whose apparent size could match these specifications, while p.15 ilustrates five pieces of conventional form, but without scale. Then, too, the Dutch participated in the trade. Did they get their manillas from nearby Antweerp as well, or did they use something different.