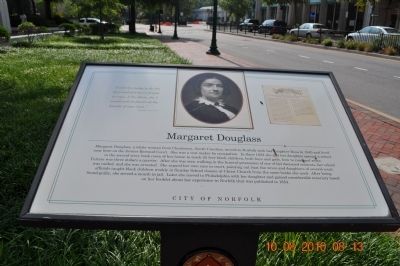

An unlikely martyr for black education, Margaret Douglass was arrested in May 1853 for violating Virginia law, eleven months after opening a school for free black children. Born in Washington, D.C., and raised in Charleston, South Carolina, she married, and had two children. After the death of her son, Douglass moved in 1845 to Norfolk, Virginia, with her daughter, Hannah Rosa. There is little record of Douglass's life in Charleston. Documents do not disclose information about her husband's death, but after arriving in Norfolk, she was the only means of support for herself and her nine-year-old daughter. Douglass became employed as a seamstress. The family worshipped at Christ Episcopal Church with many of the community's leaders. Christ Church had a Sunday school where black children received lessons in reading. A former slave owner, Douglass felt morally compelled to help teach black children how to read and write as part of her “Christian duty.” A great many Virginians, especially women, undertook to teach their own slaves to read and write, and others readily taught in Sunday schools where they emphasized the responsibility of servants to obey their masters and mistresses and to accept the status in life into which they were born.

While conducting business in Robinson's Barber Shop one day, Douglass met the owner, a free black man. She quickly learned of his five, uneducated children and offered to allow her daughter to teach them how to read and write at no charge. The positive experience with these children encouraged Douglass and her daughter to establish a school for free black children. In June 1852, Douglass opened a school in her home, charging students three dollars per quarter. The school's beginning enrollment was twenty-five boys and girls. On the morning of May 9, 1853, eleven months after opening the school, Margaret Douglass was arrested for violating Virginia law.

While conducting business in Robinson's Barber Shop one day, Douglass met the owner, a free black man. She quickly learned of his five, uneducated children and offered to allow her daughter to teach them how to read and write at no charge. The positive experience with these children encouraged Douglass and her daughter to establish a school for free black children. In June 1852, Douglass opened a school in her home, charging students three dollars per quarter. The school's beginning enrollment was twenty-five boys and girls. On the morning of May 9, 1853, eleven months after opening the school, Margaret Douglass was arrested for violating Virginia law.

At the time, in Virginia it was illegal to assemble any African Americans, free or enslaved, for the purpose of instructing them to read or write. Douglass pleaded ignorance of the law, having understood that the regulation applied to enslaved blacks only. For this reason, Douglass was careful to enroll only free blacks at her school. Although the mayor of Norfolk seemed to have dismissed Douglass's case, the local grand jury indicted her in November 1853, and she was convicted and fined one dollar. Acting in her own defense, Douglass insisted that she was not an abolitionist, that she approved of the institution of slavery in the South, that she had only tutored free blacks at her school, and that her students also attended Christ Episcopal Sunday School. When she returned to court to receive her sentence on January 10, 1854, the judge required her to serve a one-month prison sentence “as an example to all others in like cases.” She duly served her sentence, spending one week of her incarceration ill. Friendly with the jailer and his wife, she spent a few days as their guest after her sentence was completed. Soon after her release, she and her daughter moved to Philadelphia in February 1854 where Douglass published an account of her Norfolk experience and lived “happy in the consciousness that it is here no crime to teach a poor little child, of any color, to read the Word of God.”

(source: http://www.virginiamemory.com/online_classroom/shaping_the_constitution/people/margaret_douglass

This reminds me of the story of Emma Akin of Drumright Oklhoma who after 7 years was persuaded to take over the education of Drumrights negro children then went on the publish the first reading primers for black children.

ReplyDelete