On The Third Day Of Kwanzaa: Ujima

According to the

North Jersey Record, "Drop-off in Kwanzaa observations called disheartening," by Monsy Alvarado (Staff Writer), on 25 December 2013 -- The traditions of Kwanzaa will be celebrated this year in North Jersey with school assemblies, crafts at local libraries and get-togethers hosted by community groups.

However, local festivities at churches and other community sites to mark the holiday that celebrates and honors the heritage of African-Americans are harder to find, some community leaders said.

“I used to go to Kwanzaa parties by residents and some that were sponsored by churches and other civic organizations, but I don’t know, it’s not what it used to be, and it’s a little disheartening,” said Mack Cauthen, a former Englewood councilman and deacon at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Englewood.

Anthony Cureton, president of the Bergen chapter of the NAACP, said he also has noticed a decline in Kwanzaa-related activities, and he said it likely is not practiced at home, either.

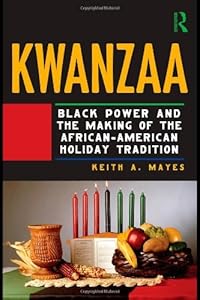

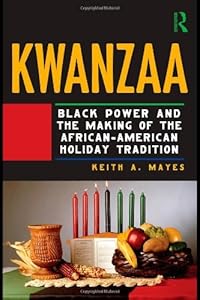

Kwanzaa: The Making of a Black Holiday Tradition -- By Keith A. Mayes

Kwanzaa: The Making of a Black Holiday Tradition -- By Keith A. Mayes

Keith A. Mayes, author of a book on Kwanzaa and an associate professor and chairman of the department of African-American and African studies at the University of Minnesota, said celebrations haven’t declined nationally, but likely leveled off since the inception of the seven-day holiday in 1966. He said Kwanzaa events can still be found on many university campuses, at cultural institutions and at museums, as well as celebrations in private homes. He said the holiday’s popularity in certain parts of the country is dependent on the black population.

“Is it celebrated as robust as it once was?” asked Mayes, who received his doctorate in history from Princeton University. “That’s the question, and it is dependent on where in the country you are.”

Mayes, whose book is titled “Kwanzaa: Black Power and The Making of the African-American Holiday Tradition,” said Kwanzaa may also be dependent on whether all of its rituals, from lighting candles to celebrating with a grand feast called Karamu, have been kept through the years by families recognizing the holiday.

“How much of Kwanzaa has been passed down is also a question,” he said.

Kwanzaa is a seven-day holiday observed from Dec. 26 to Jan. 1 to honor family, community and culture. During the holiday, observers light candles and talk about the seven principles that the red, green and black candles represent. They may also exchange handmade gifts.

The holiday was created by Maulana Karenga, who is now chairman of the department of Africana studies at California State University, Long Beach. Kwanzaa started in the midst of the civil rights movement and a year after race riots, known as the Watt Riots, left dozens dead in a neighborhood in Los Angeles.

Kwanzaa celebrates seven principles, known as the Nguzo Saba. The principles are umoja, or unity; kujichagulia, or self-determination; ujima, or collective work and responsibility; ujamaa, or cooperative economics; nia, or purpose; kuumba, or creativity; and imani, or faith.

As part of the lighting ceremony, seven candles — three red, three green, and one black — are placed in a candle holder known as a kinara. The candles are lit each day to recognize the principle that will be the focus that day.

Cauthen said he wanted to organize a Kwanzaa event in Bergen County this year after he called around and found that there weren’t many planned. But when he reached out to community members, he said very few were interested or could attend, so he dropped the idea, he said.

“It’s disheartening,’’ he said. “We scrapped this for now but will try to build it up for next year.”

The Rev. Gregory Jackson of Mount Olive Baptist Church in Hackensack said that in the past, the church has organized Kwanzaa celebrations, but such events are dependent on volunteers taking the lead, and that’s why they haven’t had any such festivities in recent years. And the Paterson Museum, which has held Kwanzaa events in the past, isn’t having one this year, either, because of other exhibits being shown there.

But a few local celebrations can be found. The principles of Kwanzaa and its history were presented to K-4 students at the Nellie K. Parker School in Hackensack last week during its Kwanzaa celebration. The students heard African musicians, saw dancers perform and sampled fare with African roots provided by parents.

Arlena Jones, one of the teachers who helped organize the assembly, said it was the first time the school had held its Kwanzaa celebration during the school day in order to expose the most students to the holiday.

Jones said the assembly was one of several that are organized at the school each year to teach children about different cultures.

“It helps build tolerance and respect,” Jones said. “You may not always agree or like what someone else believes, but you should have respect for other people’s beliefs and have tolerance.

“I have always felt that a public school should expose children to all walks of life so they can be prepared when they leave,” she added. “At Parker we do that, we expose them to different cultures, because the world is not one color.”

The school’s principal, Lillian Whitaker, said that every year, various cultural events are planned, and this year that also included a presentation on Diwali, the Indian festival of lights celebrated in the fall.

“It’s not religious, but historical, so we try to teach them a little bit of everything,” she said.

The National Coalition of 100 Black Women Bergen Passaic Chapter this year planned to integrate their annual Kwanzaa luncheon with Christmas. It marked the first year the group was not going to have an event solely for Kwanzaa. The luncheon was supposed to be held Dec. 13, at the Richard Rodda Community Center in Teaneck but was canceled due to the snowy weather. Organizers have now planned a New Year’s luncheon later next month, but it was not clear whether the Kwanzaa principles would be discussed.

At the Johnson Public Library in Hackensack, the children’s department will hold its annual Kwanzaa craft activity on Monday, where children will talk about the core principles and learn to weave a kente cloth. The activity attracts an average of 10 children, said Babette Smith, the assistant librarian in the children’s department.

“I don’t get a huge following,” she said. “And I don’t know anyone who actually celebrates it in the home, but we recognize it here, and we will do a craft every winter holiday.” (source:

North Jersey Recorder)

/_derived_jpg_q90_250x0_m0/Shaft1971-PosterArt_CR.jpg?partner=allrovi.com)

![[NguzoSaba.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiKhpiOQ9qZQxsO-h0VtCUlfsS6byUQjOvXurAP-e1BLVR_2ADrJ9iz-iC9jo1-10TMb-HnFAqZUkUUG5prLxdfcAKBM6BfxWkS7QceFMMJPfPuLYSmTMhM3KpKSFfbg6ULpfsG3ptdnXk3/s280/NguzoSaba.jpg)

![[book2.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiESwep-ia7KsLA9C8TKmT1auZYiyuIrvUQ4XU-VmIOyjW0uJY42IV_5loYvHcsZUyeMn0x6kbpaIwCJ4SgXZf8XzNdfqznH7D0r_LaUjkimaqggsaYTcQiVKAXZ3Brri1xV0mbQlj5rUvc/s280/book2.jpg)