Published in The Nation, "Was Fred Hampton Executed?" by Jeff Cohen and Jeff Gottlieb, 30 November 2009 -- Seven years after the shootings of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark by the Chicago police, a civil suit reveals the sordid details behind the assassination.

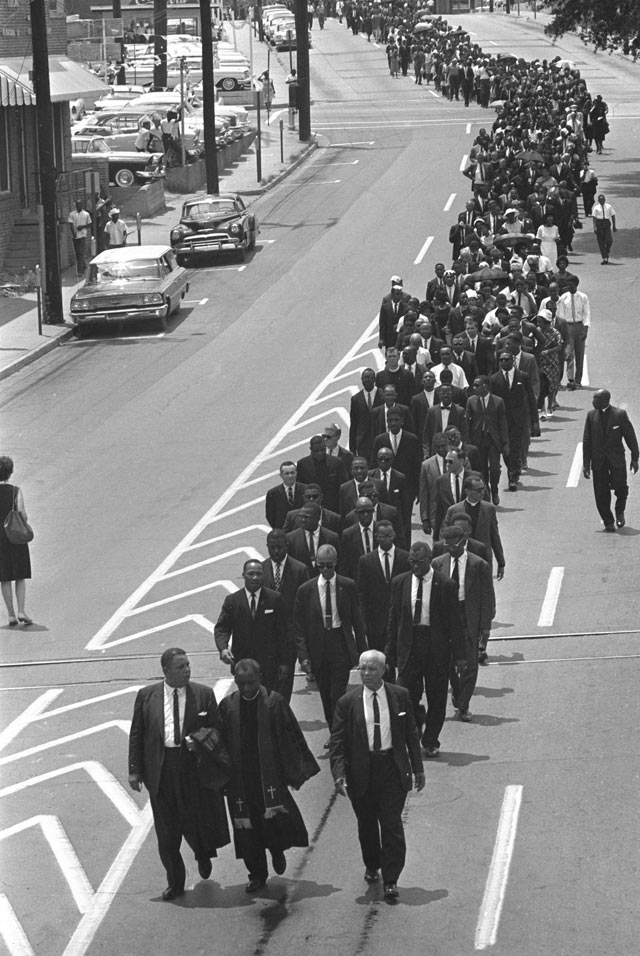

In the predawn hours of December 4, 1969, Chicago police, under the direction of the Cook County State's Attorney's Office, raided the ramshackle headquarters of the local chapter of the Black Panther Party. When the smoke cleared, Chairman Fred Hampton and party member Mark Clark were dead; four others lay seriously wounded.

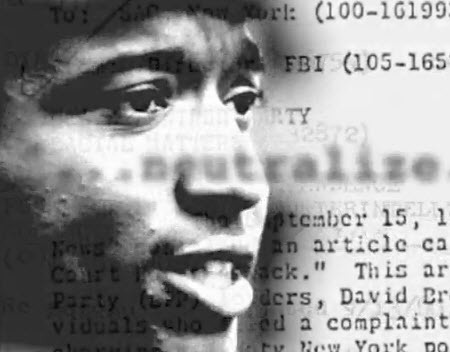

Fred Hampton (1948 – 1969)

Fred Hampton (1948 – 1969)

Today in Chicago, seven years after the raid, the facts are slowly emerging, as a civil trial crawls through its tenth month. The families of Hampton and Clark, along with the seven who survived the foray, have filed a $47.7 million damage suit. Edward Hanrahan, three former and present FBI agents, an ex-FBI informant, and twenty-six other police personnel stand accused of having conspired to violate the civil rights of the Panthers, and then of covering it up. In essence, the plaintiffs and their lawyers are out to prove that the FBI/police conspired to execute Fred Hampton.

At 17, Hampton was a black youth on the road to "making it" in white America. He was graduated from high school in Maywood, Ill, with academic honors, three varsity letters, and a Junior Achievement Award. Four years later he was dead.

As youth director of the Maywood NAACP, he had built an unusually strong 500-member youth group in a community of 27,000. After his nonviolent, integrationist activities aroused the hostility of Maywood authorities, Hampton moved to Chicago where he organized a local chapter of the Black Panther Party

.

As Panther chief in Chicago, Hampton built a reputation as a uniter, bringing together the "Rainbow Coalition" of Puerto Rican, white and black poor people, and engineering a tenuous peace among several warring ghetto gangs. His death was a blow to this multiracial united front.

Within hours of the raid, the authorities offered their explanation of what had occurred. Chicago Police Sgt. Daniel Groth, who led the fourteen police raiders, said:

There must have been six or seven of them firing. The firing must have gone on ten or twelve minutes. If 200 shots were exchanged, that was nothing.... It's a miracle that not one policeman was killed.

At a press conference that day, State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan issued a statement, saying in part:

The immediate, violent and criminal reaction of the occupants in shooting at announced police officers emphasizes the extreme viciousness of the Black Panther Party. So does their refusal to cease firing at police officers when urged to do so several times.

On December 11, the Chicago Tribune ran an account drawn from the policemen involved in the assault, and accompanied by a photograph of the apartment on which circles were drawn around what purported to be holes caused by bullets fired at the police.

Hanrahan later had a full-scale model of the apartment constructed so that the participating policemen could re-enact the raid on WBBM-TV, the local CBS affiliate. Each officer acted out his part step by step for the TV cameras as if rehearsing a scene for a SWAT episode in slow motion. One cop said that as soon as he announced he was a police officer, occupants of the apartment responded with shotgun fire. Two raiders demonstrated how as they approached the front room, they were greeted by a woman who fired a shotgun blast at them as they stood in the doorway. Another cop explained how he had fired through a door and then received return fire, presumably from Mark Clark.

Despite the elaborate re-enactment for TV and the explanations given by the fourteen policemen, it soon became apparent that the official version was at variance with the facts. The "bullet holes" in the Tribune photograph turned out to be nail heads. Although officers Groth and Davis both alleged that Brenda Harris fired a shotgun blast at the doorway as they approached, there was absolutely no evidence of such a blast.

Ultimately, a federal grand jury determined that the police had fired between eighty-three and ninety shots--the Panthers a maximum of one. The grand jury indicated that, if the Panthers fired at all, it was one shot that Mark Clark fired--apparently after he had been shot in the heart. If the cops had, in fact, demanded a ceasefire on three occasions, they were talking only to themselves. The official explanation amounted to a cover-up, and a massive one.

In attempting to resolve this issue, the raid on Chicago Panther headquarters must be put into context. That the FBI supervised a nationwide effort to destroy the Black Panther Party is no longer seen as the paranoid rantings of leftists, but as a fact documented by the Staff Report of the Church committee. The report stated that the FBI's COINTELPRO (Counter-Intelligence program) used "dangerous, degrading or blatantly unconstitutional techniques" to disrupt Left and black organizations. It went on to liken the FBI's harassment of Martin Luther King to the treatment usually afforded a Soviet agent.

On March 4, 1968 (exactly one month before King was assassinated), Hoover issued this directive:

- Prevent the Coalition of militant black nationalist groups. In unity there is strength, a truism that is no less valid for all its triteness. An effective coalition...might be the first step toward a real "Mau Mau" in America, the beginning of a true black revolution.

- Prevent the rise of a "messiah" who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement. Malcolm X might have been such a "messiah"; he is the martyr of the movement today...Elijah Muhammad is less of a threat because of his age. King could be a very real contender for this position should he abandon his supposed "obedience" to "white liberal doctrines" (nonviolence) and embrace black nationalism. Stokely Carmichael has the necessary charisma to be a real threat in this way.

This memo was drafted three weeks after the Panthers had accomplished a short-lived alliance with Stokely Carmichael and SNCC. (Until the Hampton suit released this document in full, the names had been deleted.)

After King's death, Hoover called the Panthers "the single most dangerous threat to the internal security of the United States." Of the 295 actions taken to disrupt black groups, 233 were aimed at the Panthers. The bureau's main tactic was to provoke warfare be-tween the Panthers and other black organizations. These actions, according to the Staff Report, "involved risk of serious bodily injury or death to the targets."

Over the years of COINTELPRO, the FBI paid out more than $7.4 million in wages to informants and provocateurs, more than twice the amount allocated to organized crime informants. Operating out of forty-one field offices, COINTELPRO agents supervised agents-provocateurs, placed "snitch jackets" on bona-fide Panthers by having them mis-labeled as informants, and drafted poison-pen letters and cartoons in attempts to incite violence against the Panthers, and divide the party leadership.

All the weapons in COINTELPRO's arsenal were used against the rising "black mes-siah," Chairman Hampton of the Illinois Black Panther Party. Documents released by the suit have exposed the local "get-Hampton" campaign. Roy Mitchell, a.defendant in the case and an ace handler of FBI informants, testified that he had between seven to nine informants in the Chicago Panthers at the time of the raid. Adding that number to those working for the state and the Gang Intelligence Unit of the Chicago Police, one comes up with approximately thirty informants reporting on about sixty-five active members. The names of these informants have been deleted from the documents. This estimate does not include any informants working for the CIA or military intelligence, a subject which the plaintiffs have not been allowed to probe.

One informant whose name we do know, William O'Neal, figures very prominently in the case. He was planted in the chapter almost from its inception and soon became head of security. Among his many schemes as security chief was the construction of an electric chair to be used on informers. It was disassembled on Hampton's orders. After the raid, O'Neal suggested to remaining party members that the steps leading to the apartment on W. Monroe be electrified so that any future raiders would be fried.

Not simply an informant, O'Neal tried to provoke others into "kamikaze"-type activities. Former Panther member Louis Truelock has submitted an affidavit stating that during a visit to O'Neal's father's home, the informer showed him putty, blasting caps and "plastic bottles of liquid," enough material to produce several bombs. He proposed that they blow up an armory and later suggested robbing a McDonald's restaurant. Truelock and others who heard O'Neal's provocative proposals rejected them as useless to the cause.

Although he was infatuated with weapons and tried to involve other Panthers in criminal activities, O'Neal was tolerated because he was an exceptionally hard worker around the office. Ronald "Doc" Satchel, a Panther leader who was wounded in the raid, recalls, "The only person who didn't want O'Neal in the Panthers was Fred Hampton."

O'Neal was also instructed to carry out the FBI's "divide-and-conquer" plan. The bureau most feared a pact between the Panthers and the Blackstone Rangers, Chicago's most powerful black gang. Defendant Marlin Johnson, former Chicago FBI chief, now head of the Chicago Police Board, and a defendant in the present trials, testified before the Church committee that he approved the sending of an anonymous letter to Ranger leader Jeff Fort which read, "The brothers that run the Panthers blame you for blocking their thing and there's supposed to be a hit out for you.... I know what to do if I was you." When pressed for an explanation, Johnson claimed that he thought a hit "is some-thing nonviolent in nature," and maintained that the letter-writing scheme was aimed at preventing violence. He added, "We didn't think he [Fort] would pay too much attention to the letter."

William O'NeaI's crowning achievement was his advance work on the December 4 raid. Two weeks before the attack, he provided the FBI with a detailed floor plan of Panther headquarters, complete with an "X" over Fred Hampton's bed. Most of the shots were fired at that spot.

Following the lethal raid, O'Neal was rewarded with a $300 bonus after Agent Robert Piper, also a defendant in the suit, explained in a memo to Washington, "Our source [O'Neal] was the man who made the raid possible." In another memo, listing the amounts and dates that O'Neal was paid, the bureau acknowledged his information on national Panther leaders, anti-war activists from the New Mobilization Committee and the Chicago 8, and the furnishing of the floor plan: "It is noted that most information pro-vided by this source is not available from any other source." O'Neal was so valuable that Roy Mitchell once dished out $1,600 to buy him a car and $1,000 to bail him out of jail.

When FBI agents began to shop around for a police agency to raid Panther headquar-ters, they approached the Chicago Police Department twice, in October and November 1969, but were turned down both times. The FBI then approached Cook County State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan, who agreed to carry out the operation. Hanrahan, in a TV interview, said that he agreed to the raid after the FBI told him that the Panthers were stockpiling illegal weapons at their headquarters. However, on November 19, O'Neal had reported to the FBI that the guns had been legally obtained. This was corroborated by Maria Fisher, an infiltrator who worked for both the FBI and the state.

The raid was originally scheduled for December, 3 at 8 P.M., but the State's Attorney's office, without notifying the FBI, postponed it by several hours, on the stated ground that it would be too dangerous to move in while the occupants were awake. But the floor plan submitted by O'Neal specifically marked Hampton's bed, and some people wonder what the real reason was for the delay.

It was not the first time Black Panther headquarters had been raided. In June 1969, a force led by FBI Agent Marlin Johnson, but also involving other police agencies, met no resistance when the raiders informed those inside of their intent to search the office, allegedly for a fugitive. O'Neal admitted in a deposition that he had set up that raid. No fugitive was found, but several Panthers were arrested on a variety of charges, all of which were later dropped. The point is that, once the authorities announced themselves, the Panthers made no attempt to resist.

At 4:30 on the morning of December 4, police raiders burst into the apartment with their guns ablaze. Harold Bell, one of the wounded survivors, testified that everyone immediately surrendered. Bell and two others, including Hampton's girl friend, Deborah John-son, were ordered out of Hampton's bedroom, where he lay motionless. Then, says Bell, police fired from point-blank range into Hampton's body. Bell's testimony about Hampton's execution-style death has been supported by Deborah Johnson and other survivors. Johnson testified that, after emptying his gun into Hampton's bed, the cop walked away muttering, "He's good and dead now."

Why didn't Hampton get out of bed and try to resist? Photographs of his blood-soaked mattress make it obvious that he did not. According to the independent Commission of Inquiry, headed by NAACP chief Roy Wilkins and former Atty. Gen. Ramsey Clark, there are strong indications that he had been drugged. About three hours before the shooting, at 1:30 A.M. Hampton was in bed talking to his mother on the telephone, when he fell asleep in mid-conversation. Deborah Johnson tried to rouse him but failed. During the raid others tried to wake him, but his only movement was to raise his head briefly. And, of course, the sound of gunfire is not usually conducive to sleep.

The day after the raid, the Cook County coroner performed the first of four official autopsy examinations. It "failed to show the presence of barbiturates." Later postmortems by the coroner's office, the FBI and a federal grand jury also failed to turn up any trace of barbiturates. However, an independent autopsy and blood analysis which were performed at the request of the Hampton family by Dr. Victor Levine, former chief pathologist for the Cook County coroner's office, and Dr. Eleanor Berman, a toxicologist and acting director of the Department of Biochemistry at Cook County Hospital, found a potentially lethal quantity of drugs in Fred Hampton's bloodstream -- a dosage which, at the least, would have induced a coma.

The Commission of Inquiry attempted to resolve these differences. It consulted experts who concluded that technical errors had been made during the official autopsies. The scientists found no reason to reject the Berman-Levine verdict.

With up to nine informants inside the Panthers, including the resourceful William O'Neal, the FBI had ample opportunity to have the chairman drugged. Informant Maria Fisher has asserted in a signed statement to the Chicago Daily News that one week before the killings, local FBI chief Marlin Johnson asked her to slip Hampton a colorless and taste-less drug which would put him to sleep so that the FBI could raid the apartment. She says that when she refused, Johnson told her she was "being very foolish."

O'Neal has admitted in a deposition that he was in Hampton's apartment on December 3, but his memory is hazy as to the precise time. A criminal associate of his testified under oath, in another case, that, one time when he and O'Neal were high on marijuana, O'Neal said that the raid on the Panthers was unnecessary because he had drugged Hampton the night of the assault.

Robert Piper, a defendant and the FBI agent in charge of the "Racial Matters" squad in Chicago throughout 1968-9, admitted on the stand that the Black Panthers had broken no laws and had never been prosecuted locally. He testified that the FBI's sole purpose was to harass the group and contribute to its breakup.

Within months of the raid, a federal grand jury roundly criticized the police, but offered no indictments. Panther attorney G. Flint Taylor provided an explanation when he stated in court: "I have a document from the government showing that there was a deal that there would be no indictments [of Hanrahan and the police] in return for Hanrahan's dropping of indictments [against the survivors of the raid].

Because of rising anger in Chicago's black community at the failure to indict any law-enforcement officials, Joseph Power, Chief Judge of the Cook County Criminal Court, established a special county grand jury on June 27, 1970. Barnabas Sears, a prominent Chicago lawyer, was appointed special prosecutor and promised a free hand in investigating the affair.

Rumors began making the rounds in late April 1971 that indictments against Hanrahan and other police officials were imminent. But when the grand jury handed Power an envelope containing the indictments, the judge sought to prevent their return by refusing to open the envelope. The matter was resolved on August 24 by a unanimous opinion from the seven-man Illinois State Supreme Court that "the interests of justice would best be served by opening the indictment and proceeding pursuant to the law." The indictments against Hanrahan and thirteen others for conspiracy to obstruct justice in the investigation that followed the raid were finally made public. Still, no one was held accountable for the deaths of Hampton and Clark.

The obstruction of justice case went to trial on July 10, 1972, with Cook County Criminal Court Judge Philip Romiti presiding without a jury. At the close of the prosecution's case, defense attorneys for Hanrahan and the police moved for an acquittal on the ground that not enough evidence had been presented to convict. The judge granted the motion.

Against this backdrop, the civil suit began on January 5, 1976. Now the familiar court-room roles have been reversed--never before have the Black Panthers been the plain-tiffs, with law-enforcement officials the defendants. Judge Joseph Sam Perry is on the bench. In November 1975, lawyers for the plaintiffs asked for his removal on the ground that at the age of 79, Perry is too old and too deaf to function competently. He has given credence to these objections by several times falling asleep in court. Attorneys for the victims also contend that he is unable to understand the complexities of the case.

One of Perry's first rulings was to eliminate many defendants from the suit, including Mayor Daley; former Police Chief James Conlisk, Cook County; the estate of J. Edgar Hoover, and seven officials of the FBI or Justice Department. The judge also dismissed complaints against Hanrahan and his assistants, but was overruled on appeal.

Although the Northern District of Illinois has a 31 per cent black population, only 6 per cent of the 400 prospective jurors were black. Panther attorneys watched helplessly as one of their best prospects disqualified herself with an honest answer. When asked if she could judge the word of an FBI agent without prejudice, the prospective juror re-plied, "Judge, to tell you the truth, with all I've been reading recently about them, I think I would find it difficult." Ultimately, one elderly black woman ended up on the six-person jury.

At the start, Perry told prospective jurors that both sides have agreed "there was a gun battle." If that had been true, there would be no civil suit. The basis of the plaintiffs' case is that only one bullet, and perhaps none at all, was fired at police, and that conclusion is endorsed by the federal grand jury and the Commission of Inquiry's report, Search and Destroy. Calling this a gun battle is like calling the assassination of Martin Luther King a duel.

Lawyers for both sides feel that Perry committed a reversible error by delaying the enforcement of Panther subpoenas for FBI files until two days before the trial opened. Up to then Perry had declared FBI files inadmissible unless they mentioned the name of Hampton or Clark, his explanation being that "the Black Panther Party is not on trial here." The judge has since conceded that his mistake on the Panther subpoenas, and a second blunder, have been responsible for greatly prolonging the proceedings. Perry's second error was to give the defense a free hand in deleting "irrelevant" information from the files.

In January, Richard Held, then head of the FBI's Chicago field office and now an associate director of the bureau, was served with a subpoena, signed by Perry, calling for all FBI documents relevant to the case. Held appointed FBI Agent Robert Piper, a defendant in the case, and some fifteen agents working under him, to make deletions from these files. Justice Department lawyers repeatedly assured the court that the order to deliver all relevant material had been complied with. However, in mid-March, during testimony from defendant Roy Mitchell, it came out that 90 percent of the file had been withheld. This included 130 volumes of information, a stack of papers 30 feet high. Mitchell let that cat out of the bag when he referred to a document that Panther attorneys had never seen.

Immediately, lawyers for the plaintiffs called for contempt citations against seven Justice Department and FBI officials, including defense attorneys Kanter and Kwoka, and FBI agents Piper and Held. Complaints by Roy Wilkins and an open letter from two Illinois state legislators prompted Attorney General Levi to appoint Assistant US Attorney Charles Kocoras to head an inquiry into the matter of the hidden documents. This choice was criticized because Kocoras had prosecuted a case in which FBI informant O'Neal and Agent Mitchell were the main government witnesses. Lawyer Taylor called the selection of Kocoras "like naming John Mitchell to investigate Watergate."

Kocoras was soon replaced by another Assistant US Attorney, Stephen Kadison. An aide to Kadison told the authors that, although plaintiffs' lawyers and FBI agents have been among those interviewed, the probe is an internal Justice Department matter, and that the findings may not be revealed publicly. After seven months, no conclusions have been announced.

The dispute over the documents placed the Hampton case on the front pages of the lo-cal papers for one of the few times during the trial. Because of this, Perry agreed to a plea from defense attorney Camilio Volini that the jury be polled to determine if any member was aware of the controversy. During the polling, one juror pulled a clipping of a Chicago Daily News story from her purse. The judge immediately stopped the canvassing process because it could, in his words, "lay the ground for a mistrial."

At the next court session Volini reiterated his motion to poll. In a surprise move, the Panther lawyers joined in the request, probably the only time both sides have agreed on anything. As all ten lawyers converged on the bench arguing in favor of the motion, the overwhelmed judge shouted, "Just leave me alone!" Perry regained his composure in time to deny the motion, saying, "I have confidence that this jury is not going to be influenced by a few headlines. The court disagrees with all parties, and I happen to be the final word."

Perry then announced to the jury that it was his fault, not the defendants', that the case was being delayed because of the withheld documents. Defense attorneys were stunned when the judge took the blame for what appeared to be suppression of vital information by the defendants.

In mid-April Panther lawyers renewed their call for a mistrial, this time asking for a default judgment because of "wholesale deceit, bad faith, and manipulation of evidence by the FBI defendants and the US Attorney's Office." Perry stated hat he would delay a ruling on the motion until the end of the trial.

The 130 volumes of FBI documents were finally turned over to the plaintiffs, but not be-fore the bureau tried to charge them $17,353 for labor and materials in making the copies. According to Taylor, Judge Perry said he wanted to assess those charges to the Panthers but could find no law to back him up.

The plaintiffs are faced with the problem of how to digest and utilize the mass of new material. The judge would not postpone the trial. Once, when attorney Haas asked per-mission to delay an interrogation until he could study the relevant FBI documents, a flushed Perry rose from the bench and yelled, "You're stalling, you're stalling, you're stalling." When fellow counsel Taylor answered, "No, we are not," Perry ordered him to sit down or be found in contempt. When Dennis Cunningham, a third Panther lawyer, attempted to say something, Perry screamed at him, "Sit down or you'll be held in con-tempt of court!" Needless to say, permission for a postponement was not granted.

As the trial inches along, the taxpayers continue to foot the bill for those who planned and carried out the raid. Cook County and the city of Chicago are paying for the defense of Hanrahan, his assistants, the fourteen raiders, and other police personnel to the tune of $20,000 per week. The federal government is covering the defense of the three agents and O'Neal. The cost is already well beyond $1 million and the trial isn't ex-pected to end until March 1977 at the earliest.

While the defense is well funded, financial woes have beset the plaintiffs. The Panther legal staff cannot afford to buy daily transcripts, an indispensable resource, but one that would cost $50,000 for the trial. The lawyers' request to make copies from the judge's or defense's transcripts was denied, but Perry agreed that they could inspect his when necessary.

Fred Hampton had been fond of proclaiming, "You can kill a revolutionary, but you can-not kill a revolution. You can jail a liberation fighter, but you cannot jail liberation." Be-tween 1968 and 1971, more than a score of Panthers were killed by police agencies, and more than 1,000 were jailed. That the party has survived at all is a minor miracle. While the death of Fred Hampton dealt a crippling blow to the Illinois chapter, the char-ter chapter in Oakland has never been stronger. The party currently runs fifteen, free "survival programs" in its Oakland stronghold, including free clothing, legal aid, ambulance, pest control, plumbing and maintenance, a breakfast for children programs, a food co-op, medical clinics and the Oakland Community School.

Although many talk about the FBI's destruction of the Black Panther Party as if it were a fait accompli, perhaps it is too early to discard the favorite slogan of exiled Panther leader, Huey Newton: "The spirit of the people will defeat the technology of the Man." (source:

The Nation, URL: http://www.thenation.com/article/was-fred-hampton-executed)

.jpg)