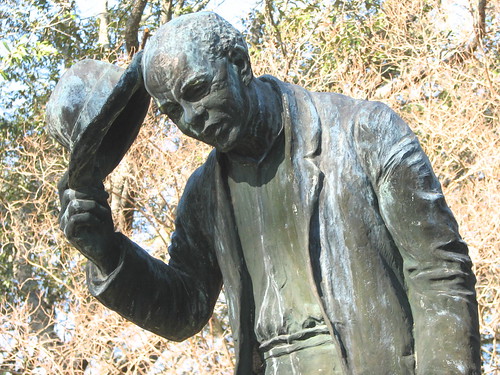

Colfax Courthouse, Louisiana

From the Washington Post Book Review, "A Massacre and a Travesty," Reviewed by Eric Foner, on 23 March 2008 -- Unbeknownst to most Americans, our nation's history includes home-grown terrorism as well as attacks from abroad. Scholars estimate that during Reconstruction, the turbulent period that followed the Civil War, upwards of 3,000 persons were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan and kindred groups. That's roughly the same number of Americans who have died at the hands of Osama bin Laden.

In the last generation, no part of the American past has undergone a more complete scholarly reinterpretation than Reconstruction. Once portrayed as a tragic era of rampant misgovernment presided over by unscrupulous carpetbaggers and ignorant former slaves, Reconstruction is today seen as a noble, if flawed, experiment in interracial democracy, an effort to provide free blacks with land, education and political rights. The tragedy is not that Reconstruction was attempted, but that it failed.

The work of historians, however, has largely failed to penetrate popular consciousness. Partly because of the persistence of old misconceptions, Reconstruction remains widely misunderstood. Popular views still owe more to such films as "Birth of a Nation" (which glorified the Klan as the savior of white civilization) and "Gone With the Wind" (which romanticized slavery and the Confederacy) than to modern scholarship.

Thus, the new books by LeeAnna Keith and Charles Lane are doubly welcome. Not only do they tell the story of the single most egregious act of terrorism during Reconstruction (a piece of "lost history," as Keith puts it), but they do so in vivid, compelling prose. Keith, who teaches at the Collegiate School in New York, and Lane, a journalist who covered the Supreme Court for The Washington Post, have immersed themselves in the relevant sources and current historical writing. Both accomplish a goal often aspired to but rarely achieved, producing works of serious scholarship accessible to a non-academic readership.

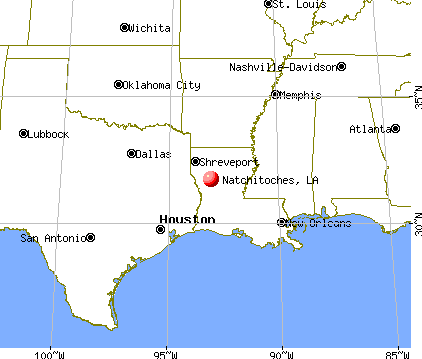

The Colfax massacre took place on Easter Sunday 1873, when a force of about 150 heavily armed whites assaulted an equal number of blacks, many of them militia members, holed up in the courthouse at Colfax, La. After chivalrously allowing women and children to leave, they overran the outgunned defenders. Some blacks were killed trying to escape; 40 or so were taken prisoner and then executed. The final death toll remains unknown -- Lane estimates between 62 and 81, Keith thinks it may have reached 150. Three whites also died.

Both authors offer a gripping account of the assault and subsequent atrocities. But overall, their books complement rather than repeat each other. While shorter, Keith's is more comprehensive, devoting more space to the history of slavery, emancipation and Reconstruction in west-central Louisiana. She explores the brutal nature of slavery on the sugar and cotton plantations of local magnate Meredith Calhoun, one of the richest men in the United States. Calhoun seems to have been the model for Simon Legree, the cruel master in Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. Ironically, after the war, his son William became a leading proponent of blacks' rights. He lived openly with a black woman, rented land to black farmers, established a school for their children and aligned himself with the Republican party.

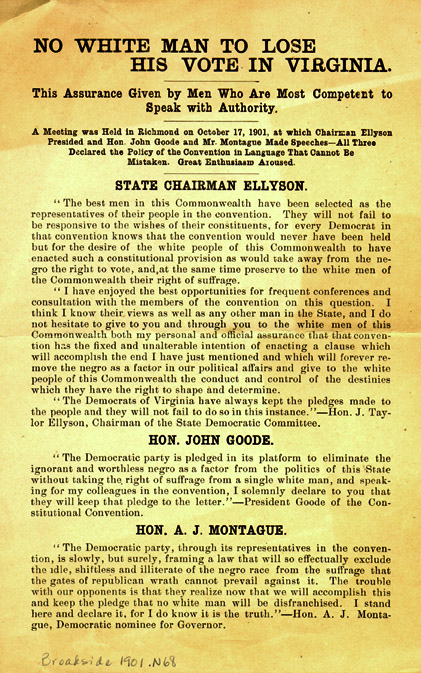

In his bestselling book, April 1865: The Month that Saved America (2001), the journalist Jay Winik commended defeated Confederates for returning to peaceful pursuits after Appomattox, thus "saving" the United States from the agony of a long guerrilla war. Would that this were so. Organized violence emerged around Colfax almost as soon as the Civil War ended, targeting black leaders, school teachers, freedmen who tried to acquire land, and, once blacks won the right to vote, local officeholders. Not all the victims were black -- Delos White, a Freedman's Bureau agent, was assassinated in 1871. What happened in Colfax was not atypical. "Murder," Keith writes laconically, "played a central role in Louisiana and throughout the region" during Reconstruction.

"The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction," By Charles Lane

While Keith illuminates the massacre's historical context, Lane offers a far more detailed account of the ensuing court cases. If his story has a hero, it is J. R. Beckwith, the U.S. attorney in New Orleans, who became obsessed with bringing the perpetrators to justice. He received little assistance from his superior, Attorney General George H. Williams, who thought it would be better if the murderers simply fled the state. Beckwith persuaded a federal grand jury to indict nearly 100 men under the recently passed Enforcement Acts, which made it a federal crime to deprive citizens of constitutionally guaranteed rights. But because of local white resistance, only a handful of those charged could be arrested.

Eventually, nine men went on trial before a biracial jury. Dozens of witnesses, almost all of them black, related what had happened at Colfax. The initial trial resulted in a hung jury; a second produced the conviction of three defendants. But Supreme Court Justice Joseph P. Bradley, acting while on circuit court duties, voided the indictment because, he insisted, most of the rights that had allegedly been violated were matters of state, not federal, authority.

"The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, and the Death of Reconstruction," By LeeAnna Keith

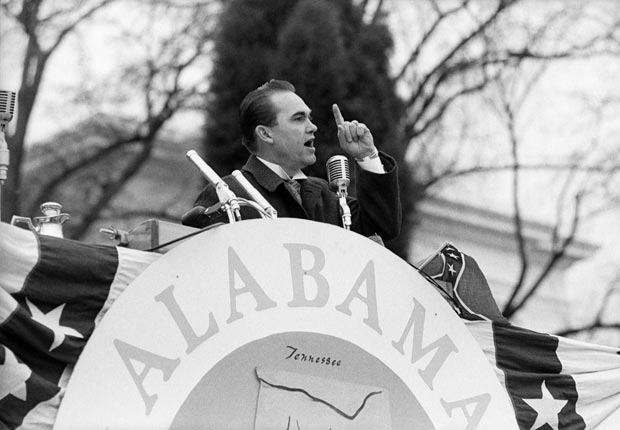

Because the presiding judge courageously refused to go along with Bradley, his judicial superior, the case went to the Supreme Court. In 1876, in U.S. v. Cruikshank, the justices unanimously threw out the convictions. As Lane points out, nowhere in Chief Justice Morrison Waite's 5,000-word opinion did he mention the fact that dozens of black men had been murdered in cold blood at Colfax. Cruikshank hammered the final nail into the coffin of federal efforts to protect the basic rights of black citizens in the South. Reconstruction effectively ended a year later, and the Jim Crow era began.

This tragic story is more than ancient history. Into the 20th century, bones turned up in Colfax when the foundations for buildings were being laid. There still stands in the town a plaque, erected in 1951, commemorating the Colfax "riot" -- not massacre -- and "the end of carpetbag misrule in the South." As recently as eight years ago, Chief Justice William Rehnquist cited Cruikshank as a precedent in overturning a conviction under the Violence Against Women Act. The Constitution, he declared, gives the states, not the federal government, the power to punish rape. Whether we realize it or not, Reconstruction and its overthrow remain part of our lives today. *

Eric Foner, DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University, is the author, most recently, of "Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction." (source: The Washington Post)