From the

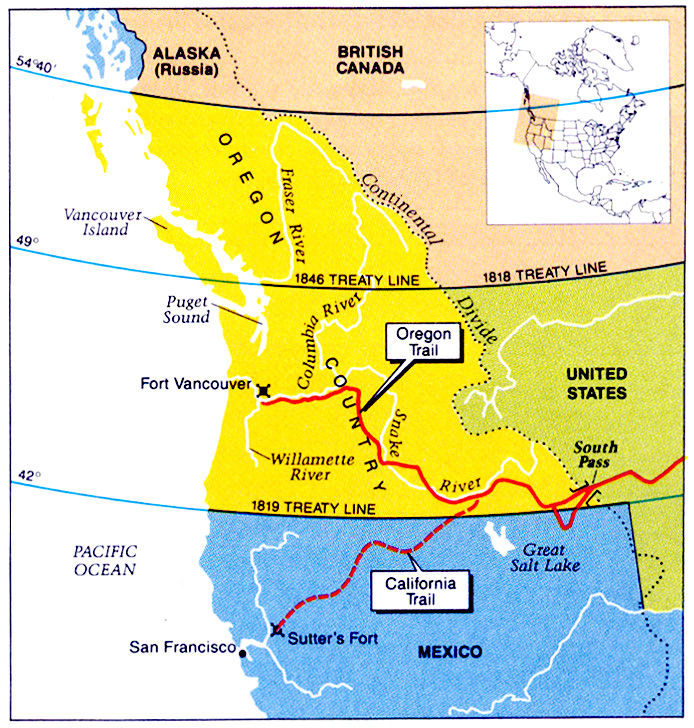

Texas State Historical Association -- SLAVERY. Texas was the last frontier of slavery in the United States. In fewer than fifty years, from 1821 to 1865, the "Peculiar Institution," as Southerners called it, spread over the eastern two-fifths of the state. The rate of growth accelerated rapidly during the 1840s and 1850s. The rich soil of Texas held much of the future of slavery, and Texans knew it. James S. Mayfield undoubtedly spoke for many when he told the Constitutional Convention of 1845 that "the true policy and prosperity of this country depend upon the maintenance" of slavery. Slavery as an institution of significance in Texas began in Stephen F. Austin's colony. The original empresario commission given Moses Austin by Spanish authorities in 1821 did not mention slaves, but when Stephen Austin was recognized as heir to his father's contract later that year, it was agreed that settlers could receive eighty acres of land for each bondsman brought to Texas. Enough of Austin's original 300 families brought slaves with them that a census of his colony in 1825 showed 443 in a total population of 1,800. The independence of Mexico cast doubt on the future of the institution in Texas. From 1821 until 1836 both the national government in Mexico City and the state government of Coahuila and Texas threatened to restrict or destroy black servitude. Neither government adopted any consistent or effective policy to prevent slavery in Texas; nevertheless, their threats worried slaveholders and possibly retarded the immigration of planters from the Old South. In 1836 Texas had an estimated population of 38,470, only 5,000 of whom were slaves. The Texas Revolution assured slaveholders of the future of their institution. The Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836) provided that slaves would remain the property of their owners, that the Texas Congress could not prohibit the immigration of slaveholders bringing their property, and that slaves could be imported from the United States (although not from Africa). Given those protections, slavery expanded rapidly during the period of the republic. By 1845, when Texas joined the United States, the state was home to at least 30,000 bondsmen. After statehood, in antebellum Texas, slavery grew spectacularly. The census of 1850 reported 58,161 slaves, 27.4 percent of the 212,592 people in Texas, and the census of 1860 enumerated 182,566 bondsmen, 30.2 percent of the total population. Slaves were increasing more rapidly than the population as a whole.

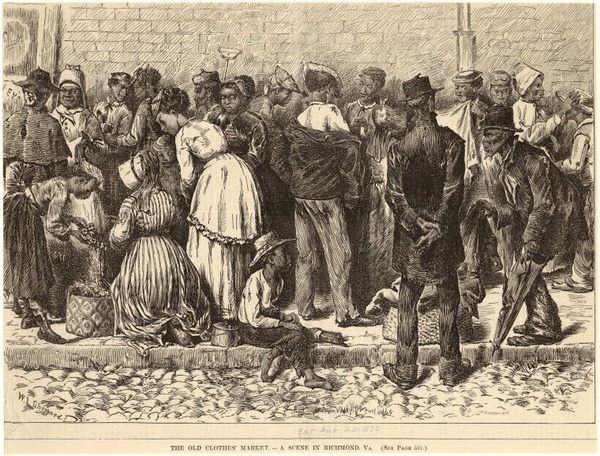

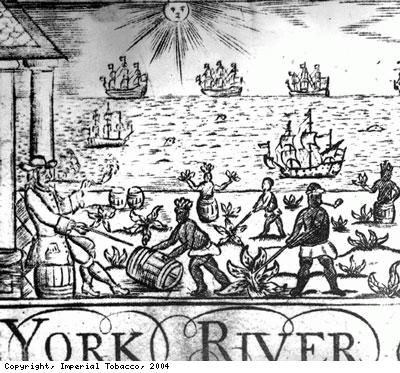

The great majority of slaves in Texas came with their owners from the older slave states. Sizable numbers, however, came through the domestic slave trade. New Orleans was the center of this trade in the Deep South, but there were slave dealers in Galveston and Houston, too. A few slaves, perhaps as many as 2,000 between 1835 and 1865, came through the illegal African trade.

Slave prices inflated rapidly as the institution expanded in Texas. The average price of a bondsman, regardless of age, sex, or condition, rose from approximately $400 in 1850 to nearly $800 by 1860. During the late 1850s, prime male field hands aged eighteen to thirty cost on the average $1,200, and skilled slaves such as blacksmiths often were valued at more than $2,000. In comparison, good Texas cotton land could be bought for as little as six dollars an acre. Slavery spread over the eastern two-fifths of Texas by 1860 but flourished most vigorously along the rivers that provided rich soil and relatively inexpensive transportation. The greatest concentration of large slave plantations was along the lower Brazos and Colorado rivers in Brazoria, Matagorda, Fort Bend, and Wharton counties. Truly giant slaveholders such as Robert and D. G. Mills, who owned more than 300 bondsmen in 1860 (the largest holding in Texas), had plantations in this area, and the population resembled that of the Old South's famed Black Belt. Brazoria County, for example, was 72 percent slave in 1860, while north central Texas, the area from Hunt County west to Jack and Palo Pinto counties and south to McLennan County, had fewer slaves than any other settled part of the state, except for Hispanic areas such as Cameron County. However, the north central region held much excellent cotton land, and slavery would probably have developed rapidly there once rail transportation was built. The last frontier of slavery was by no means closed on the eve of the Civil War.

American slavery was preeminently an economic institution-a system of unfree labor used to produce cash crops for profit. Questions concerning its profitability are complex and always open to debate. The evidence is strong, however, that in Texas slaves were generally profitable as a business investment for individual slaveholders. Slave labor produced cotton (and sugar on the lower Brazos River) for profit and also cultivated the foodstuffs necessary for self-sufficiency. The effect of the institution on the state's general economic development is less clear. Slavery certainly promoted development of the agricultural economy; it provided the labor for a 600 percent increase in cotton production during the 1850s. On the other hand, the institution may well have contributed in several ways to retarding commercialization and industrialization. Planters, for example, being generally satisfied with their lives as slaveholders, were largely unwilling to involve themselves in commerce and industry, even if there was a chance for greater profits. Slavery may have thus hindered economic modernization in Texas. Once established as an economic institution, slavery became a key social institution as well. Only one in every four families in antebellum Texas owned slaves, but these slaveholders, especially the planters who held twenty or more bondsmen, generally constituted the state's wealthiest class. Because of their economic success, these planters represented the social ideal for many other Texans. Slavery was also vital socially because it reflected basic racial views. Most whites thought that blacks were inferior and wanted to be sure that they remained in an inferior social position. Slavery guaranteed this.

Lake Jackson Plantation, home of Abner and Margaret Jackson and headquarters of a thriving sugar refinery. First slaves, then convicts provided the backbreaking labor necessary to grow and process the cane. This photograph, taken prior to 1900, preserves the mansion's final days before a hurricane destroyed many of the buildings on the plantation. Image courtesy Brazoria County Historical Museum. (source: Texas Beyond History)

Although the law contained some recognition of their humanity, slaves in Texas generally had the legal status of personal property. They could be bought and sold, mortgaged, and hired out. They had no legally prescribed way to gain freedom. They had no property rights themselves and no legal rights of marriage and family. Slaveowners had broad powers of discipline subject only to constitutional provisions that slaves be treated "with humanity" and that punishment not extend to the taking of life and limb. A bondsman had a right to trial by jury and a court-appointed attorney when charged with a crime greater than petty larceny. Blacks, however, could not testify against whites in court, a prohibition that largely negated their constitutional protection. Bondsmen who did not work satisfactorily or otherwise displeased their owners were commonly punished by whipping. Many slaves may have escaped such punishment, but every bondsman lived with the knowledge that he could be whipped at his owner's discretion.

The majority of adult slaves were field hands, but a sizable minority worked as skilled craftsmen, house servants, and livestock handlers. Field hands generally labored "from sun to sun" five days a week and half a day on Saturday. House servants and craftsmen worked long hours, too, but their labor was not so burdensome physically. Theirs was apparently a favored position, at least in this regard. A small minority (about 6 percent) of the slaves in Texas did not belong to farmers or planters but lived instead in the state's towns, working as domestic servants, day laborers, and mechanics .

After the emancipation of slaves in Texas in 1865, sugar growers leased prisoners from the state prison system to continue operations in the fields and mills. Photo : Brazoria County Historical Museum.

The material conditions of slave life in Texas could probably best be described as adequate, in that most bondsmen had the food, shelter, and clothing necessary to live and work effectively. On the other hand, there was little comfort and no luxury. Slaves ate primarily corn and pork, foods that contained enough calories to provide adequate energy but were limited in essential vitamins and minerals. Most bondsmen, however, supplemented their basic diet with sweet potatoes, garden vegetables, wild game, and fish and were thus adequately fed. Slave houses were usually small log cabins with fireplaces for cooking. Dirt floors were common, and beds attached to the walls were the only standard furnishings. Slave clothing was made of cheap, coarse materials; shoes were stiff and rarely fitted. Medical care in antebellum Texas was woefully inadequate for whites and blacks alike, but slaves had a harder daily life and were therefore more likely to be injured or develop diseases that doctors could not treat (see HEALTH AND MEDICINE). Texas slaves had a distinct family-centered social life and culture that flourished in the slave quarters, where bondsmen were largely on their own, at least from sundown to sunup. Although slave marriages and families had no legal protections, the majority of bondsmen were reared and lived day to day in a family setting. This was in the slaveowners' self-interest, for marriage encouraged reproduction under socially acceptable conditions, and slave children were valuable. Moreover, individuals with family ties were probably more easily controlled than those who had none. The slaves themselves, however, also insisted on family ties. They often made matches with bondsmen on neighboring farms and spent as much time as possible together, even if one owner or the other could not be persuaded to arrange for husband and wife to live on the same place. They fought bitterly against the disruption of their families by sale or migration and at times virtually forced masters to respect family ties. Many slave families, however, were disrupted. All slaves had to live with the knowledge that their families could be broken up, and yet the basic social unit survived. Family ties were a source of strength for people enduring bondage and a mark of their humanity, too. Religion and music were also key elements of slave culture. Many owners encouraged worship, primarily on the grounds that it would teach proper subjection and good behavior. Slaves, however, tended to hear the message of individual equality before God and salvation for all. The promise of ultimate deliverance helped many to resist the psychological assault of bondage. Music and song served to set a pace for work and to express sorrow and hope.

Slaves adjusted their behavior to the conditions of servitude in a variety of ways. Some felt well-treated by their owners and generally behaved as loyal servants. Others hated their masters and their situation and rebelled by running away or using violence. Texas had many runaways, and thousands escaped to Mexico. Although no major rebellions occurred, individual acts of violence against owners were carried out. Most slaves, however, were neither loyal servants nor rebels. Instead, the majority recognized all the controls such as slave patrols that existed to keep them in bondage and saw also that runaways and rebels generally paid heavy prices for overt resistance. They therefore followed a basic human instinct and sought to survive on the best terms possible. This did not mean that the majority of slaves were content with their status. They were not, and even the best-treated bondsmen dreamed of freedom. Slavery in Texas was not a matter of content, well-cared for servants as idealized in some views of the Old South. On the other hand, the institution was not absolutely brutal or degrading. Slaves were not reduced to the level of animals, and they did not live every day in sullen rage. Instead, bondsmen had enough "room"-time of their own and control of their own lives-within the slave system to maintain physical, psychological, and spiritual strength. In part this limited autonomy was given by the masters, who generally wanted loyal and cheerful servants. Slaves increased their minimal self-determination by taking what they could get from their owners and then pressing for additional latitude. For example, slaves worked hard, but they tried to work at their own pace and offered many forms of nonviolent resistance if pushed too hard. Slaves in general were not revolutionaries who overcame all the limits placed on them, but they did not surrender totally to the system, either. One way or another they had enough room to endure. This fact is not a tribute to the benevolence of slavery, but a testimony to the human spirit of the enslaved blacks.

Though slaves obviously freed their owners from the drudgery of manual labor and daily chores, they were a troublesome property in many ways. Masters had to discipline their bondsmen, get the labor they wanted, and yet avoid too many problems of resistance such as running away and feigning illness. Many owners wished to appear as benevolent "fathers," and yet most knew that there would be times when they would treat members of their "families" as property pure and simple. Most lived with a certain amount of fear of their supposedly happy servants, for the slightest threat of a slave rebellion could touch off a violent reaction. Slavery was thus a constant source of tension in the lives of slaveholders.

White society as a whole in antebellum Texas was dominated by its slaveholding minority. Economically, slaveowners had a disproportionately large share of the state's wealth and produced virtually all of the cash crops. Politically, slaveholders dominated public officeholding at all levels. Socially, slaveholders, at least the large planters, embodied an ideal to most Texans.

The progress of the Civil War did not drastically affect slavery in Texas because no major slaveholding area was invaded. In general, Texas slaves continued to work and live as they had before the war. A great many did, however, get the idea that they would be free if the South lost. They listened as best they could for any war news and passed it around among themselves. Slavery formally ended in Texas after June 19, 1865 (Juneteenth), when Gen. Gordon Granger arrived at Galveston with occupying federal forces and announced emancipation. A few owners angrily told their slaves to leave immediately, but most expressed sorrow at the end of the institution and asked their bondsmen to stay and work for wages. The emancipated slaves celebrated joyously (if whites allowed it). But then they had to find out just what freedom meant. They knew that they would not be forced to labor anymore and that they could move about as they chose. But how would they make their way in the world after 1865? Blacks had maintained a degree of human dignity even in bondage (most owners had allowed them to do so), and Texas could not have grown as it had before 1865 without the slaves' contributions. Nevertheless, slavery was a curse to Texans, white and black alike. (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/yps01)