From the Washington Post, "New Deal, Raw Deal: How Aid Became Affirmative Action for Whites," by Ira Katznelson, 27 September 2005 -- Hurricane Katrina's violent winds and waters tore away the shrouds that ordinarily mask the country's racial pattern of poverty and neglect. Understandably, most commentators have focused on the woeful federal response. Others, taking a longer view, yearn for a burst of activism patterned on the New Deal. But that nostalgia requires a heavy dose of historical amnesia. It also misses the chance to come to terms with how the federal government in the 1930s and 1940s contributed to the persistence of two Americas.

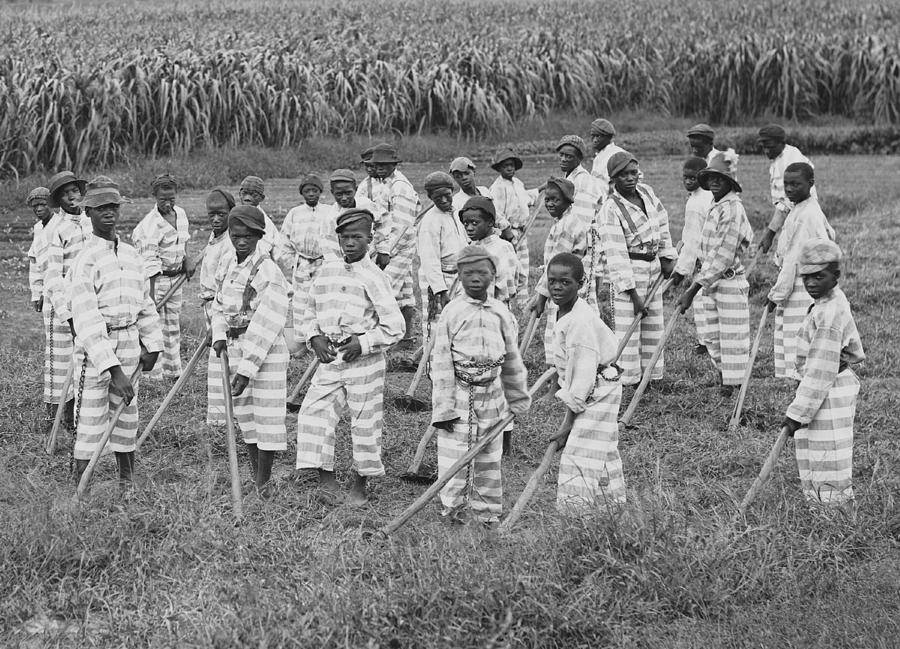

It was during the administrations of Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman that such great progressive policies as Social Security, protective labor laws and the GI Bill were adopted. But with them came something else that was quite destructive for the nation: what I have called "affirmative action for whites." During Jim Crow's last hurrah in the 1930s and 1940s, when southern members of Congress controlled the gateways to legislation, policy decisions dealing with welfare, work and war either excluded the vast majority of African Americans or treated them differently from others.

Between 1945 and 1955, the federal government transferred more than $100 billion to support retirement programs and fashion opportunities for job skills, education, homeownership and small-business formation. Together, these domestic programs dramatically reshaped the country's social structure by creating a modern, well-schooled, homeowning middle class. At no other time in American history had so much money and so many resources been targeted at the generation completing its education, entering the workforce and forming families.

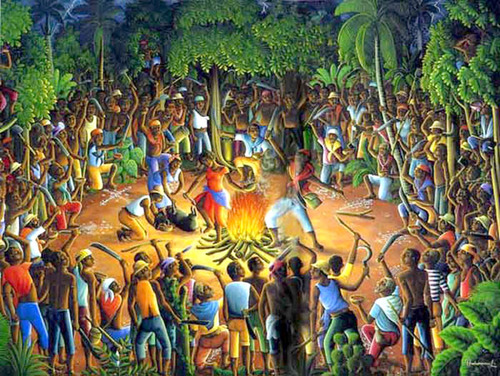

But most blacks were left out of all this. Southern members of Congress used occupational exclusions and took advantage of American federalism to ensure that national policies would not disturb their region's racial order. Farmworkers and maids, the jobs held by most blacks in the South, were denied Social Security pensions and access to labor unions. Benefits for veterans were administered locally. The GI Bill adapted to "the southern way of life" by accommodating itself to segregation in higher education, to the job ceilings that local officials imposed on returning black soldiers and to a general unwillingness to offer loans to blacks even when such loans were insured by the federal government. Of the 3,229 GI Bill-guaranteed loans for homes, businesses and farms made in 1947 in Mississippi, for example, only two were offered to black veterans.

This is unsettling history, especially for those of us who keenly admire the New Deal and the Fair Deal. At the very moment a wide array of public policies were providing most white Americans with valuable tools to gain protection in their old age, good jobs, economic security, assets and middle-class status, black Americans were mainly left to fend for themselves. Ever since, American society has been confronted with the results of this twisted and unstated form of affirmative action.

A full generation of federal policy, lasting until the civil rights legislation and affirmative action of the 1960s, boosted whites into homes, suburbs, universities and skilled employment while denying the same or comparable benefits to black citizens. Despite the prosperity of postwar capitalism's golden age, an already immense gap between white and black Americans widened. Even today, after the great achievements of civil rights and affirmative action, wealth for the typical white family, mainly in homeownership, is 10 times the average net worth for blacks, and a majority of African American children in our cities subsist below the federal poverty line.

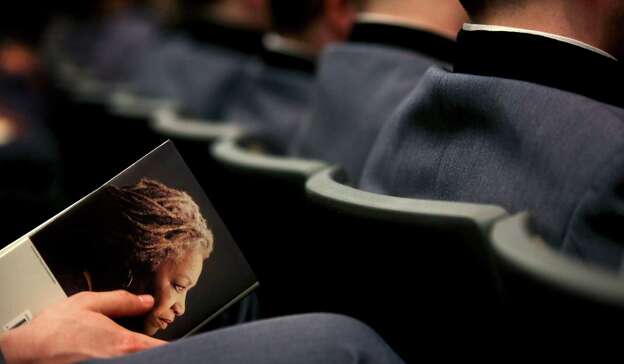

President Lyndon Johnson faced up to racial inequality in "To Fulfill These Rights," a far-reaching graduation speech he delivered at Howard University in June 1965. He noted that "freedom is not enough" because "you do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and they say, 'you are free to compete with all the others,' and still justly believe you have been completely fair." What is needed, he argued, is a set of new policies, a dramatic new type of affirmative action for "the poor, the unemployed, the uprooted, and the dispossessed." He had in mind the kind of comprehensive effort the GI Bill had provided to most returning soldiers, but without its exclusionary pattern of implementation.

This form of assertive, mass-oriented affirmative action never happened. By sustaining and advancing a growing African American middle class, the affirmative action we did get has done more to advance fair treatment across racial lines than any other recent public policy, and thus demands our respect and support. But as the scenes from New Orleans vividly displayed, so many who were left out before have been left out yet again.

Rather than yearn for New Deal policies that were tainted by racism, or even recall the civil rights and affirmative action successes of the 1960s and beyond, we would do better in present circumstances to return to the ambitious plans Johnson announced but never realized to close massive gaps between blacks and whites, and between more and less prosperous blacks.

Without an unsentimental historical understanding of the policy roots of black isolation and dispossession, and without an unremitting effort to cut the Gordian knot joining race and class, our national response to the disaster in the Gulf Coast states will remain no more than a gesture. (source: The Washington Post © 2005 The Washington Post Company)

Ira Katznelson, a professor of political science and history at Columbia University, is the author of "When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in America."