From the New York Times, "Political Racism in the Age of Obama," by Steven Hahn, on 10 November 2012 -- THE white students at Ole Miss who greeted President Obama’s decisive re-election with racial slurs and nasty disruptions on Tuesday night show that the long shadows of race still hang eerily over us. Four years ago, when Mr. Obama became our first African-American president by putting together an impressive coalition of white, black and Latino voters, it might have appeared otherwise. Some observers even insisted that we had entered a “post-racial” era.

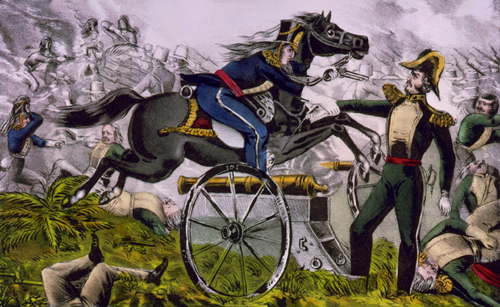

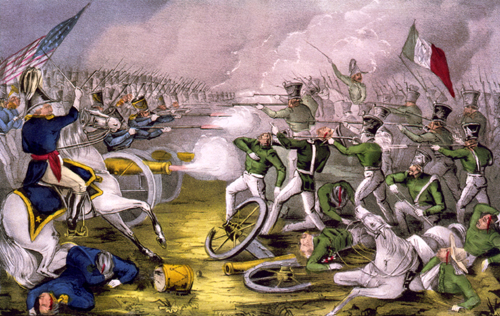

But while that cross-racial and ethnic coalition figured significantly in Mr. Obama’s re-election last week, it has frayed over time — and may in fact have been weaker than we imagined to begin with. For close to the surface lies a political racism that harks back 150 years to the time of Reconstruction, when African-Americans won citizenship rights. Black men also won the right to vote and contested for power where they had previously been enslaved.

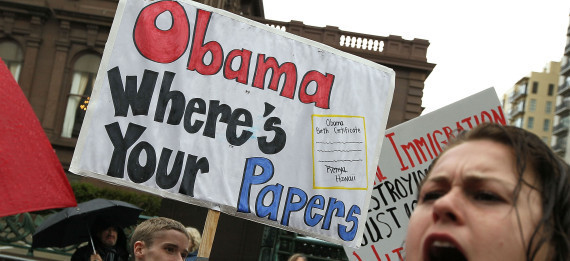

How is this so? The “birther” challenge, which galvanized so many Republican voters, expresses a deep unease with black claims to political inclusion and leadership that can be traced as far back as the 1860s. Then, white Southerners (and a fair share of white Northerners) questioned the legitimacy of black suffrage, viciously lampooned the behavior of new black officeholders and mobilized to murder and drive off local black leaders.

Much of the paramilitary work was done by the White League, the Ku Klux Klan and other vigilantes, who destroyed interracial Reconstruction governments and helped pave the road to the ferocious repression, disenfranchisement and segregation of the Jim Crow era.

D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film, “The Birth of a Nation,” which played to enthusiastic audiences, including President Woodrow Wilson, gave these sensibilities wide cultural sanction, with its depiction of Reconstruction’s democratic impulses as a violation of white decency and its celebration of the Klan for saving the South and reuniting the nation.

By the early 20th century the message was clear: black people did not belong in American political society and had no business wielding power over white people. This attitude has died hard. It is not, in fact, dead. Despite the achievements of the civil rights movement, African-Americans have seldom been elected to office from white-majority districts; only three, including Mr. Obama, have been elected to the United States Senate since Reconstruction, and they have been from either Illinois or Massachusetts.

The truth is that in the post-Civil War South few whites ever voted for black officeseekers, and the legacy of their refusal remains with us in a variety of forms. The depiction of Mr. Obama as a Kenyan, an Indonesian, an African tribal chief, a foreign Muslim — in other words, as a man fundamentally ineligible to be our president — is perhaps the most searing. Tellingly, it is a charge never brought against any of his predecessors.

But the coordinated efforts across the country to intimidate and suppress the votes of racial and ethnic minorities are far more consequential. Hostile officials regularly deploy the language of “fraud” and “corruption” to justify their efforts much as their counterparts at the end of the 19th century did to fully disenfranchise black voters.

Although our present-day tactics are state-issued IDs, state-mandated harassment of immigrants and voter-roll purges, these are not a far cry from the poll taxes, literacy tests, residency requirements and discretionary power of local registrars that composed the political racism of a century ago. That’s not even counting the hours-long lines many minority voters confronted.

THE repercussions of political racism are ever present, sometimes in subtle rather than explicit guises. The campaigns of both parties showed an obsessive concern with the fate of the “middle class,” an artificially homogenized category mostly coded white, while resolutely refusing to address the deepening morass of poverty, marginality and limited opportunity that disproportionately engulfs African-American and Latino communities.

At the same time, the embrace of “small business” and the retreat from public-sector institutions as a formula for solving our economic and social crises — evident in the policies of both parties — threaten to further erode the prospects and living standards of racial and ethnic minorities, who are overwhelmingly wage earners and most likely to find decent pay and stability as teachers, police officers, firefighters and government employees.

Over the past three decades, the Democrats have surrendered so much intellectual ground to Republican anti-statism that they have little with which to fight back effectively. The result is that Mr. Obama, like many other Democrats, has avoided the initiatives that could really cement his coalition — public works projects, industrial and urban policy, support for homeowners, comprehensive immigration reform, tougher financial regulation, stronger protection for labor unions and national service — and yet is still branded a “socialist” and coddler of minorities. Small wonder that the election returns indicate a decline in overall popular turnout since 2008 and a drop in Mr. Obama’s share of the white vote, especially the vote of white men.

But the returns also suggest intriguing possibilities for which the past may offer us meaningful lessons. There seems little doubt that Mr. Obama’s bailout of the auto industry helped attract support from white working-class voters and other so-called Reagan Democrats across the Midwest and Middle Atlantic, turning the electoral tide in his favor precisely where the corrosions of race could have been very damaging.

The Republicans, on the other hand, failed to make inroads among minority voters, including Asian-Americans, and are facing a formidable generational wall. Young whites helped drive the forces of conservatism and white supremacy during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but now most seem ill at ease with the policies that the Republican Party brandishes: social conservatism, anti-feminism, opposition to same-sex marriage and hostility to racial minorities. The anti-Obama riot at Ole Miss, integrated 50 years ago by James H. Meredith, was followed by a larger, interracial “We Are One Mississippi” candlelight march of protest. Mr. Obama and the Democrats have an opportunity to bridge the racial and cultural divides that have been widening and to begin to reconfigure the country’s political landscape. Although this has always been a difficult task and one fraught with peril, history — from Reconstruction to Populism to the New Deal to the struggle for civil rights — teaches us that it can happen: when different groups meet one another on more level planes, slowly get to know and trust one another, and define objectives that are mutually beneficial and achievable, they learn to think of themselves as part of something larger — and they actually become something larger.

Hard work on the ground — in neighborhoods, schools, religious institutions and workplaces — is foundational. But Mr. Obama, the biracial community organizer, might consider starting his second term by articulating a vision of a multicultural, multiracial and more equitable America with the same insight and power that he once brought to an address on the singular problem of race. If he does that, with words and then with deeds, he can strike a telling blow against the political racism that haunts our country. (source: New York Times)

[Steven Hahn is a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of “A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration.” (source: New York Times)]