"Brother, I wish you to give me close attention, because I think you do not clearly understand. I want to speak to you about promises that the Americans have made. You recall the time when the Jesus Indians of the Delawares lived near the Americans, and had confidence in their promises of friendship, and thought they were secure, yet the Americans murdered all the men, women, and children, even as they prayed to Jesus?

The same promises were given to the Shawnee one time. It was at Fort Finney, where some of my people were forced to make a treaty. Flags were given to my people, and they were told they were now the children of the Americans. We were told, if any white people mean to harm you, hold up these flags and you will then be safe from all danger. We did this in good faith. But what happened? Our beloved chief Moluntha stood with the American flag in front of him and that very peace treaty in his hand, but his head was chopped by an American officer, and that American Officer was never punished.

Brother, after such bitter events, can you blame me for placing little confidence in the promises of Americans? That happened before the Treaty of Greenville. When they buried the tomahawk at Greenville, the Americans said they were our new fathers, not the British anymore, and would treat us well. Since that treaty, here is how the Americans have treated us well: They have killed many Shawnee, many Winnebagoes, many Miamis, many Delawares, and have taken land from them. When they killed them, no American ever was punished, not one.

It is you, the Americans, by such bad deeds, who push the men to do mischief. You do not want unity among tribes, and you destroy it. You try to make differences between them. We, their leaders, wish them to unite and consider their land the common property of all, but you try to keep them from this. You separate the tribes and deal with them that way, one by one, and advise them not to come into this union. Your states have set an example of forming a union among all the Fires, why should you censure the Indians for following that example?

But, Brother, I mean to bring all the tribes together, in spite of you, and until I have finished, I will not go to visit your President. Maybe I will when I have finished, maybe. The reason I tell you this, you want, by making your distinctions of Indian tribes and allotting to each particular tract of land, to set them against each other, and thus to weaken us. You never see an Indian come, do you, and endeavor to make the white people divide up? You are always driving the red people this way! At last you will drive them into the Great Lake, where they can neither stand nor walk.

Brother, you ought to know what you are doing to the Indians. Is it by direction of the president you make these distinctions? It is a very bad thing, and we do not like it. Since my residence at Tippecanoe, we have tried to level all distinctions, to destroy village chiefs, by whom all such mischief is done. It is they who sell our lands to the Americans. Brother, these lands that were sold and the goods that were given for them were done by only a few. The Treaty of Fort Wayne was made through the threats of Winnemac, but in the future we are going to punish those chiefs who propose to sell the land.

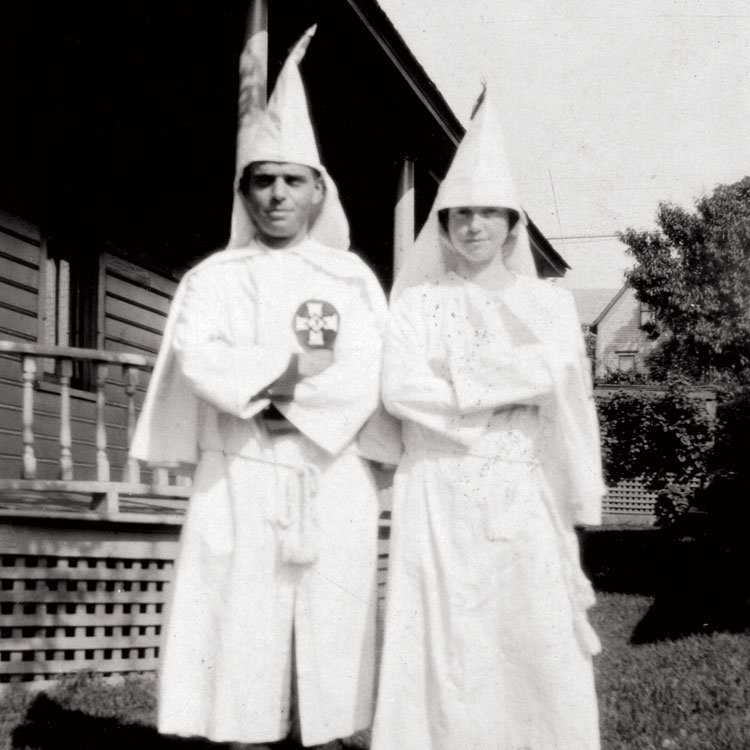

Tecumseh Shawnee Chieftain And William Henry Harrison

The only way to stop this evil is for all the red men to unite in claiming an equal right in the land. That is how it was at first, and should be still, for the land never was divided, but was for the use of everyone. Any tribe could go to an empty land and make a home there. No groups among us have a right to sell, even to one another, and surely not to outsiders who want all, and will not do with less. Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds, and the Great Sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children?

Brother, I was glad to hear what you told us. You said that if we could prove that the land was sold by people who had no right to sell it, you would restore it. I will prove that those who did sell did not own it. Did they have a deed? A title? NO! You say those proves someone owns land. Those chiefs only spoke a claim, and so you pretended to believe their claim, only because you wanted the land. But the many tribes with me will not agree with those claims. They have never had a title to sell, and we agree this proves you could not buy it from them. If the land is not given back to us, you will see, when we return to our home from here, how it will be settled. It will be like this:

We shall have a great council, at which all tribes will be present. We shall show to those who sold that they had no rights to the claims they set up, and we shall see what will be done to those chiefs who did sell the land to you. I am not alone in this determination, it is the determination of all the warriors and red people who listen to me. Brother, I now wish you to listen to me. If you do not wipe out that treaty, it will seem that you wish to kill all the chiefs who sold the land! I tell you so because I am authorized by all tribes to do so! I am the head of them all! All my warriors will meet together with me in two or three moons from now. Then I will call for those chiefs who sold you this land, and we shall know what to do with them. If you do not restore the land, you will have had a hand in killing them!

I am Shawnee! I am a warrior! My forefathers were warriors. From them I took my birth into this world. From my tribe I take nothing. I am the master of my own destiny! And of that I might make the destiny of my red people, of our nation, as great as I concieve to in my mind, when I think of Weshemoneto, who rules this universe! The being within me hears the voice of the ages, which tells me that once, always, and until lately, there were no white men on all this island, that it then belonged to the red man, children of the same parents, placed on it by the Great Spirit who made them, to keep it, to traverse it, to enjoy its yield, and to people it with the same race. Once they were a happy race! Now they are made miserable by the white people, who are never contented but are always coming in! You do this always, after promising not to anyone, yet you ask us to have confidence in your promises. How can we have confidence in the white people? When Jesus Christ came upon the earth, you killed him, the son of your own God, you nailed him up!! You thought he was dead, but you were mistaken. And only after you thought you killed him did you worship him, and start killing those who would not worship him. What kind of people is this for us to trust?

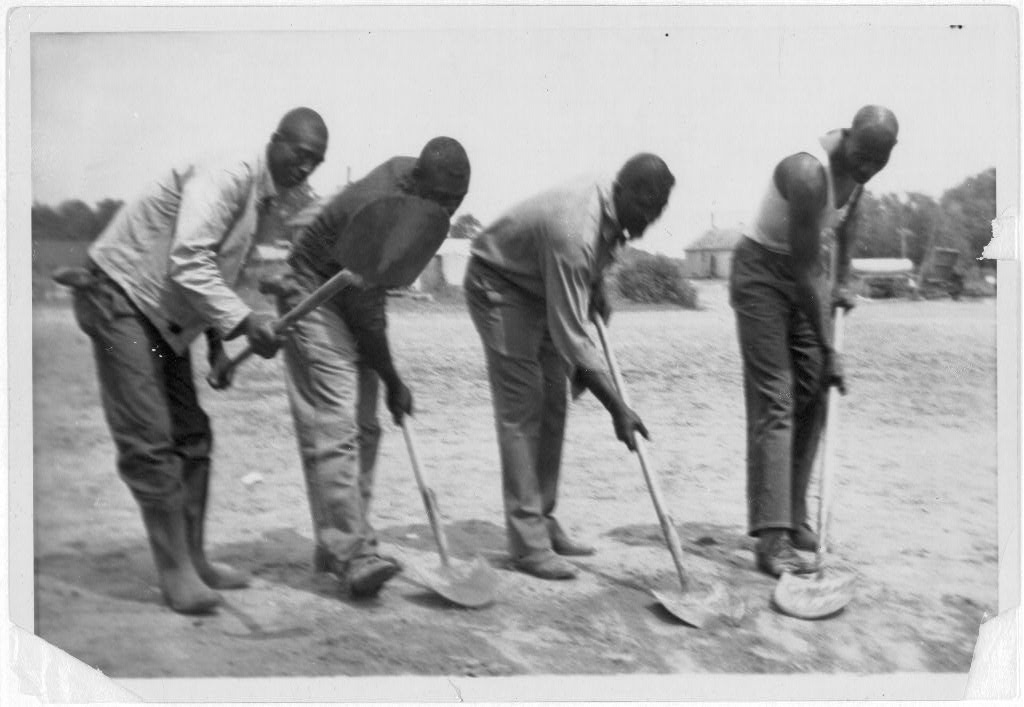

Native American Tribes of Indiana

Now, Brother, everything I have said to you is the truth, as Washemoneto has inspired me to speak only truth to you. I have declared myself freely to you about my intentions. And I want to know your intentions. I want to know what you are going to do about taking our land. I want to hear you say that you understand now, and you will wipe out that pretended treaty, so that the tribes can be at peace with each other, as you pretend you want them to be. Tell me, Brother. I want to know.