From the

Gilder Leherman Institute of American History, "The Emancipation Proclamation: Bill of Lading or Ticket to Freedom?" by Allen C. Guelzo

Of all the speeches, letters, and state papers he had written, Abraham Lincoln believed that the greatest of them was his Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. With one document of only 713 words, Lincoln declared over three million slaves in the rebel states of the Confederacy to be “thenceforward and forever free” and took the country a long step to the final abolition of slavery. Lincoln was confident “that the name which is connected with this act will never be forgotten,” and that the Proclamation would prove to be “the central act of my administration, and the great event of the nineteenth century.”

Despite that confidence, the Emancipation Proclamation remains a document shrouded in misunderstanding, and it is not too much to say that today it is probably Lincoln’s least-admired presidential paper. That misunderstanding clusters around three nagging questions:

Why did Lincoln take so long? If Lincoln was as anti-slavery as he claimed to be (“I am naturally anti-slavery,” he told Albert Hodges and Thomas Bramlette in 1864. “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel.”), why didn’t Lincoln decree emancipation in 1861, when the Civil War began, rather than waiting until 1863? “How come it took him two whole years to free the slaves?” asked the suspicious black militant Julius Lester. “His pen was sitting on his desk the whole time.”

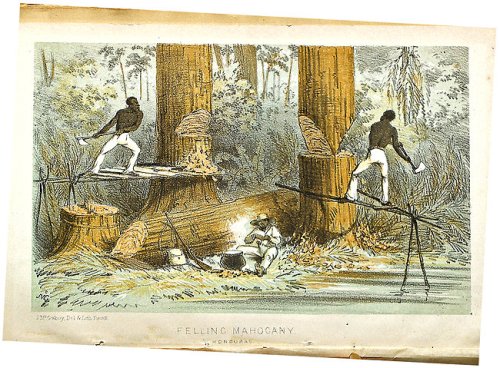

Emancipation Proclamation Map

Why is it so incomplete? The Proclamation limited emancipation to the “states or parts of states” still in rebellion, and did not include the border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, where slavery was legal but where the state governments had stayed loyal to the Union. Nor did it include large portions of the Confederacy in Virginia and Louisiana, then securely occupied by federal troops. On the surface, this looks ridiculous. In the border states, where Lincoln actually had Union soldiers on the ground who could compel the emancipation of slaves, he did nothing, but in the Confederate states, where he no longer had such power, he proclaimed an emancipation that no one could enforce. As the London Times smirked, “Where he has no power Mr. Lincoln will set the negroes free; where he retains power he will consider them as slaves.”

Why is it so bland? Surely, the author of the Second Inaugural and the Gettysburg Address could make an Emancipation Proclamation the occasion for the most stirring and sublime prose in American political history. Instead, the Emancipation Proclamation is written in the flat legal language of whereas and therefore and military necessity. As historian Richard Hofstadter said, “The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, had all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading.”

Taken together, what these questions hint at is that Lincoln issued the Proclamation at best reluctantly and at worst insincerely. In reality, the questioners add, Lincoln’s only real concern in waging the Civil War was the restoration of the Union and making the American economy safe for whites, not freedom and equality for blacks. Beyond its propaganda value for the Union war effort, the Proclamation did nothing, and was intended to do nothing.

The three questions that cast doubt on Lincoln’s good intentions are not cheap shots. By the time Hofstadter wrote off the Proclamation in 1948, American blacks had gained little from the Emancipation Proclamation beyond the bare fact of emancipation itself. Jim Crow ruled the South, and Brown v. Board of Education was still six years in the future. So if it was legitimate to wonder what good emancipation had achieved at that point, it was legitimate to wonder whether the Proclamation that decreed it was somehow flawed.

But it is always risky to assume from historical results what the actual historical intentions were, and even riskier to jump to conclusions that certain intentions were calculating, rather than straightforward. And in the case of the Emancipation Proclamation, what the questioners lack is a grip on the actual circumstances—legal, political, and military—that surrounded Lincoln and the Proclamation.

Take, for starters, the complaint about the long delay between the start of the Civil War in 1861 and the issue date of the Proclamation in 1863. The fact is that Lincoln was already drafting emancipation plans as early as November 1861, but because these are not emancipation proclamations, we routinely fail to see them as part of the long ramp that Lincoln was traveling toward the Proclamation. In the fall of 1861, Lincoln composed an experimental emancipation plan for the state of Delaware (one of those four border states). Under Lincoln’s proposal, the Delaware legislature would pass a bill, immediately freeing all Delaware slaves over the age of thirty-five and gradually freeing all others when they reached that age; in return, Congress would pay the state of Delaware just over $700,000 in United States bonds, which would then be used by the Delaware legislature to finance compensation for Delaware slave owners who would lose their slave “property” to emancipation. Under an optional accelerated timetable, slavery in Delaware could have been extinguished as early as 1872.

A buy-out is not as dramatic as a proclamation, but the end result would have been the same, and Lincoln had good reason for thinking that this plan was, in fact, the best way to make the extinction of slavery legally permanent. After all, American slavery was the creation of state, not federal, enactments, and in this era before the Fourteenth Amendment and the “incorporation” doctrine, a constitutional firewall separated the state and federal governments. Good lawyer that he was, Lincoln had no reason to believe that proclamations, presidential or otherwise, would penetrate that wall. If anything, a presidential emancipation decree would be followed by a procession of slave owners into the federal courts the next morning, complaining of unconstitutional interference by the president in state matters. Considering that the federal court system had been stocked for sixty years with pro-Southern judicial appointees, and that the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Roger B. Taney, was the man who had written the decision in Dred Scott, barring the federal government from interfering in slaveholding in the federal territories, there was no reason to suppose that the courts wouldn’t use such cases as the means for hammering a stake through the heart of emancipation for good and for all.

But if Lincoln could use the financial leverage of the federal government to entice slave-state legislatures into doing the work of emancipation voluntarily, then the same firewall that tied his hands on the federal side would also tie the hands of the federal courts. Successful emancipation must, as Lincoln wrote to Horace Greeley in 1862, have “three main features, gradual, compensation, and [the] vote of the people,” or at least the voluntary action of their legislatures. It would cost money, to be sure, but a lot less money than a civil war was costing.

Not only was the legislative option unquestionably legal, but it had a certain momentum of its own that might hasten the end of the war. Since every slave state that took the bait of compensated emancipation diminished the territory in which slavery was legal, the existing number of slaves would be forced into a smaller and smaller area, driving the supply up as the demand decreased, since there would be fewer markets to sell slaves to. As demand dropped, so would price, and the process of emancipation, which looked so slow on paper, would accelerate as slave owners rushed to accept compensation before their slaves lost all value whatsoever. As one of Lincoln’s political friends wrote, “It seemed to him that gradual emancipation and governmental compensation” would bring slavery “to an end.”

The problem was that the border states stopped their ears and refused all cooperation. The Delaware legislature stalled over the emancipation proposal, and the congressional delegations of the other border states rejected federally financed emancipation with contempt. By the spring of 1862, the only place in which compensated emancipation had actually worked was the District of Columbia, and that was only because the federal government had (as it still does) direct legislative jurisdiction over the District.

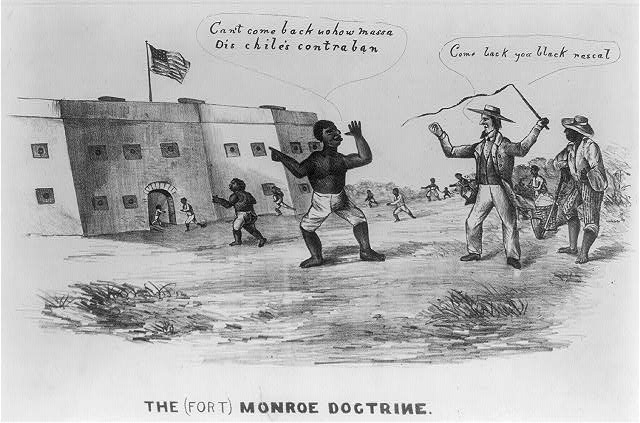

To Lincoln’s annoyance, the border states’ truculence nudged Congress into trying its own hand at emancipation in the form of the First Confiscation Act (passed on August 6, 1861), which permitted the seizure of slaves, as “property,” by the federal military if it found them working for the Confederate forces. This was followed, in July 1862, by a Second Confiscation Act, which upped the ante by granting freedom to the slaves of any slave owner in active rebellion against the United States (whether or not those slaves were actually employed in war-related service). The law also tempted two of Lincoln’s generals to dabble in even more direct schemes for emancipation. Lincoln’s headstrong commander in Missouri, John Charles Fremont, issued an emancipation edict for Missouri on August 31, 1861, and Major General David Hunter did the same in the occupied coastal district of South Carolina in May 1862.

However, neither the Confiscation Acts nor the military proclamations had much to recommend them, and this was because of the weak legal materials from which these rival emancipation plans had been created. The Confiscation Acts were modeled on the law of prize, treating slaves as similar to the cargo that a warship was entitled to capture from an enemy ship on the high seas—cargo that the ship could have a prize court sell. And Fremont’s proclamation justified itself as an act of martial law. But would any of these emancipations survive a court challenge?

The law of prize might work very well when the captured cargoes of ships belonged to the citizens of enemy nations, but confiscating enemy property on land was another matter entirely, and confiscating the property of one’s own citizens, even in cases of treason, ran afoul of the Constitution’s ban on bills of attainder. Similarly, martial law proclamations might look strong and forceful, but martial law was a tricky and mostly unexplored part of American jurisprudence in 1862. At most, martial law was understood to be only temporary, and to cover only the immediate field of a military commander’s needs—not (as Fremont’s and Hunter’s edicts implied) whole states. Similarly, it was not assumed that martial law could make permanent alterations in the legal status of property taken for military use. (A farm seized for use as a military camp did not permanently become federal property; once an army moved on; the farm remained the farmer’s property and would not be, so to speak, “emancipated.”) So Lincoln revoked the Fremont and Hunter proclamations, relieved Fremont from command, and did little to enforce the Confiscation Acts.

Lincoln’s notion of gradual, voluntary, and compensated emancipation avoided these problems because it bribed slaveholding states, through the promise of compensation, to begin emancipating slaves through their own statutes, and that got the whole process beyond the reach of the federal courts. It mattered little that a legislature might balk the first time that an emancipation plan was proposed. Drawing on his own personal experience as a state legislator back in Illinois, Lincoln knew that he only had to await the next round of state legislative elections in the fall of 1862 and 1863, at which point the financial bait might well overcome border-state resistance. But that would have required time. In the summer of 1862, time was what Lincoln ran short of, and that was largely the result of his armies and of his other generals, chief among which was Major General George B. McClellan.

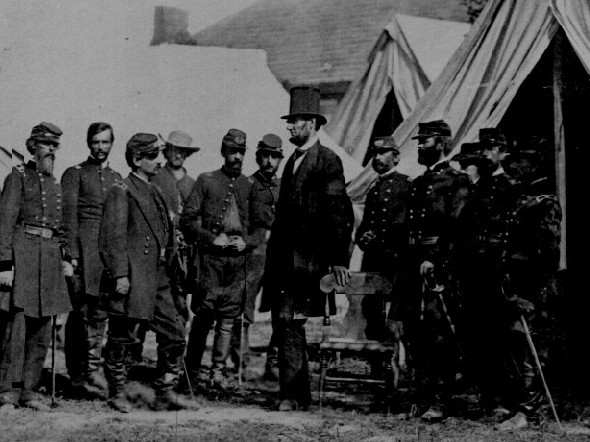

Between March and July of 1862, the Union military effort, which had begun the war with such flourishes and promises, floundered into near-catastrophe. This was partly due to a string of unexpected Confederate military successes in mid-1862, and partly from the increasingly obvious fact that the upper echelons of the federal army’s officer corps, led by McClellan, were politically hostile to both Lincoln and emancipation, and were dragging their heels in prosecuting the war. McClellan, like the leaders in the border states, made it clear that any movements toward emancipation would get no support from the Army, and might even generate outright resistance. In July 1862, when Lincoln came down to visit McClellan at his headquarters at Harrison’s Landing on the James River, McClellan served him a political ultimatum: Do nothing about slavery or the Army will no longer fight for you.

No one has been certain whether McClellan was threatening a military intervention of some sort or simply announcing that, like the border states, the federal military would do nothing to assist any emancipation plan that Lincoln had in mind. Either way, coming from an American soldier to his commander in chief, it was an ominous declaration, and Lincoln was “grieved with what he had witnessed” at Harrison’s Landing. If emancipation was to become a federal policy, it would have to be implemented without delay, either as a forthright rebuke to McClellan (on the order of Harry Truman’s riposte to Douglas MacArthur) or as a preemptive political strike before McClellan and the Army could extort some sort of cease-fire or negotiated settlement with the Confederacy. It was time, Lincoln remarked, to stop waging war “with elder stalk squirts, charged with rose water.” From that point on, he would not leave “any available means unapplied.” Two days after returning from Harrison’s Landing, Lincoln told two members of his Cabinet to look for a decisive change in emancipation policy. Ten days later, he introduced the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation at a cabinet meeting.

So, far from having done nothing for twenty months about emancipation, Lincoln had been trying to get to emancipation from the start; resorting to a proclamation was only a change in tactics, not a tardy beginning.

But why, once Lincoln did decide to reach for the “proclamation option,” did he take the border states and the occupied districts of the Confederacy off the table? It’s easy to conclude that he excluded the border and the occupation zones because he didn’t want to face the responsibility for actually implementing emancipation there. But there is a much simpler answer, and once again, it grew out of the legal and constitutional situation Lincoln was facing. No matter how much Lincoln might have wanted to emancipate the slaves in the border states, the fact was that the border states were not in rebellion. They had broken no laws and committed no act of resistance to the authority of the United States, and so long as that was the case, Lincoln had no more authority as president to emancipate slaves in those states than he did to fix prices on tomatoes. If he had any authority to proclaim emancipation anywhere, it would be only by virtue of his constitutional designation as commander in chief, and only in situations of military exigency in which he could demonstrate that such freeing served a military purpose. And that could only be in places where the rebels were still in power—not the border.

On the upside, the title of “commander in chief” gave Lincoln much broader scope for action than a mere declaration of martial law, on the model of Fremont or Hunter; on the downside, one legal slip could have brought a cascade of litigation down on his head. And if the federal courts had ever been allowed to get involved with emancipation, and decided as they had in Dred Scott, the cause of emancipation might have been set back to the dimmest possible future.

Understanding the legal technicalities surrounding emancipation also helps in answering the third question, about the flaccid language of the Proclamation. To give Richard Hofstadter his due, the Proclamation really does have all the luster of a legal brief. Try this excerpt, and see if your eyes don’t glaze over:

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander in Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned . . . order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

But what Hofstadter and the many historians who have quoted him about the Proclamation having all the grandeur of a bill of lading have missed is that the Proclamation is a legal brief. Yes, it has none of the rolling rhetorical power of the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural, but they were not legal documents, and they changed the legal status of no one. (All that the Gettysburg Address did, in literal terms, was dedicate a cemetery). The Proclamation, even with all its qualifications and reservations, seized the single most important, numerous, and profitable capital assets in the American economy in the nineteenth century, directed the recruitment of those “assets” into federal service, and shielded the whole process from court interference by invoking the language of military necessity.

It has been easy, long after the press of the legal and judicial restraints that surrounded Lincoln as president has evaporated, to start with the fact of emancipation and wonder why Lincoln did not do better or act more swiftly than he did. The real challenge is to understand with what ease Lincoln might have done nothing at all. And once we have that understanding, we can marvel at the real risks he actually took. And even if the Proclamation sounded as unheroic as a bill of lading, it was still a bill that itemized the destinies of four million human beings, bound through blood and fire for the port of American freedom. (source:

Gilder Leherman Institute of American History)

from

The Gilder Lehrman Institute on

Vimeo.