Harvard Museum of Natural History, at 26 Oxford Street, was created in 1998, combining three Oxford Street Museums under one institution--The Museum of Comparative Zoology, founded in 1859 by Swiss zoologist Louis Agassiz; the Harvard University Herbaria, founded in 1858 by Asa Gray as the Museum of Vegetable Products; and the Mineralogical and Geological Museum, founded in 1784 by Benjamin Waterhouse. The University Museum Building, which houses both the Museum of Natural History and the Peabody Museum of Archaelogy and Ethnology was originally built in 1859 and ceded to Harvard in 1876. With more than 175,000 visitors annually, the Havard Museum of Natural History is the most visited attraction at Harvard. (source: Flicker)

From

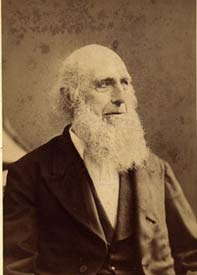

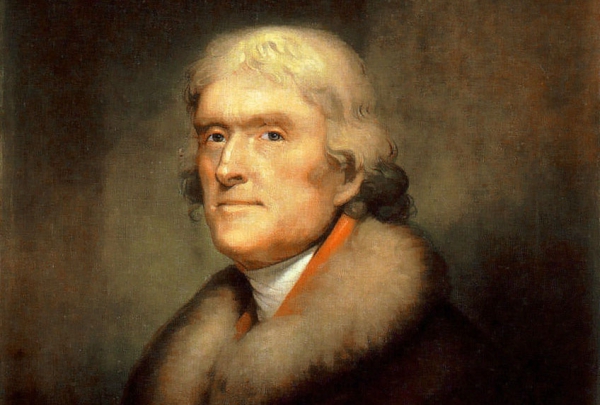

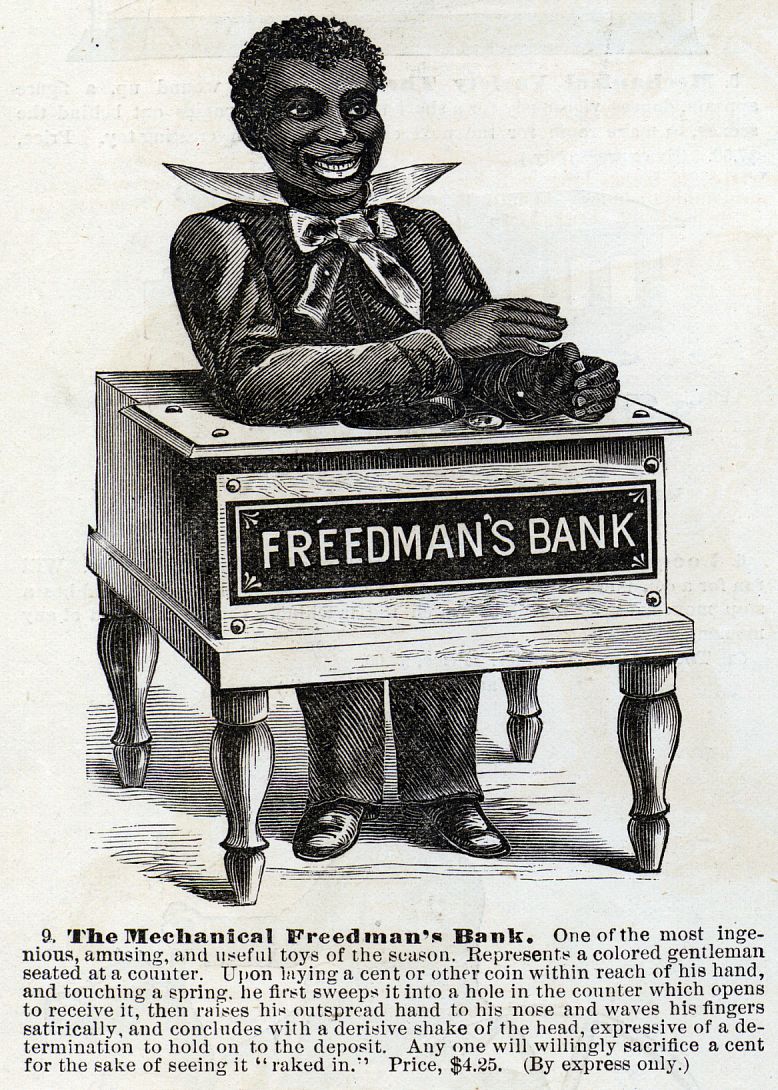

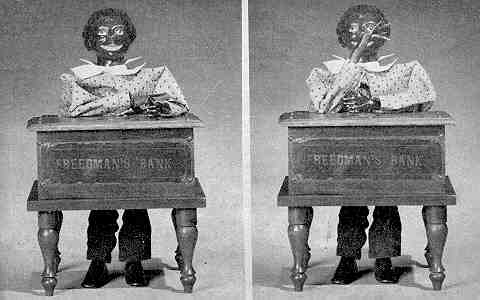

the Boston Globe, "Louis Agassiz exhibit divides Harvard, Swiss group" on 27 June 2012, by Mary Carmichael -- A Swiss group will show silhouettes of slaves. The 19th-century Swiss-born naturalist Louis Agassiz was a revered figure at Harvard University. He was also a racist who commissioned humiliating photographs of slaves and Brazilian natives.

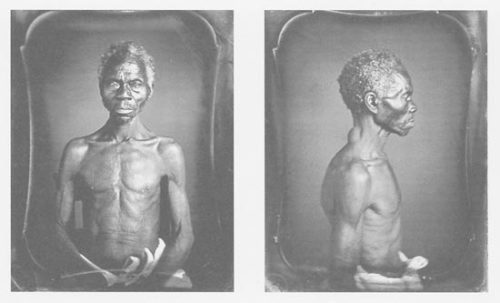

A century and a half after their creation, the images still haunt: daguerreotypes and photos of people stripped naked and displayed like specimens. To Agassiz, the images were evidence for his belief that human races sprang from different biological origins.

A Swiss group will show silhouettes of slaves.

Now, those images are at the center of a dispute between Harvard, which owns them, and the organizer of an exhibit on Agassiz and his racism that opens this week in Grindelwald, Switzerland. The images will not be reproduced in that exhibit, because Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography will not allow it.

The museum’s curators say they denied the Swiss group permission to reproduce the images because of the Peabody’s blanket policy against the display of exploitative images of naked people. Other scholars agree that there is reason to be careful with such images, lest they be used not to educate but to inflame.

Renty

The Swiss group, however, says that the Peabody never told it about the policy, nor gave it any explanation. The group’s members — a loose, unnamed confederation led by the history teacher and activist Hans Fässler, who has devoted years to exposing little-known facets of racism in Switzerland — instead argue that Harvard is protecting one of its own. They are so angry that they have decided to show silhouettes based on the images, with captions underneath that say, in essence, Harvard didn’t want you to see the real thing.

The tale of the images begins in 1850, when Agassiz, a Harvard professor, hired a South Carolina man named J.T. Zealy to make a series of daguerreotypes of slaves standing unclothed, shot from several angles.

By that time, Agassiz had already made several public statements — shocking to read today, but less so in his day. For instance, in 1846, according to the Harvard scholar Louis Menand, Agassiz said he believed that blacks and whites were different species. A year later, Agassiz told a Charleston, S.C., audience that “the brain of the Negro is that of the imperfect brain of a seven months’ infant in the womb of a White.”

But Agassiz had not finished developing his racist theories by 1850. He wanted visual evidence for them, and in Zealy he thought he had found the man to produce it.

Fifteen years later, Agassiz led an expedition to Brazil. Among the photographs of flora and fauna taken on the expedition were other images, of native people. Many, as in the Zealy daguerreotypes, were stripped to show the physical differences that Agassiz believed he saw.

Jack the Driver

Agassiz’ views on race may have left some of his colleagues disquieted. But not many.

“Agassiz’ racism was extreme in the sense that he used his public stature as a scientist to propagate and, in a bizarre way, to ‘prove’ it,” said Christoph Irmscher, an Indiana University professor and author of a new biography of Agassiz. “But his views were not extraordinarily different from the racism many of his contemporaries displayed at the time.”

Instead of being condemned, Agassiz became famous, and at the time of his death in 1873 was considered America’s leading scientist. His admirers named many landmarks for him, including a Cambridge street, a Swiss mountain, the world-class Harvard zoology museum he founded, and a public school that was later renamed.

Delia, daughter of Renty

But no one kept track of the images from South Carolina and Brazil. They disappeared for decades, surfacing only when a Peabody employee discovered them in a storage cabinet at the Harvard museum in 1976.

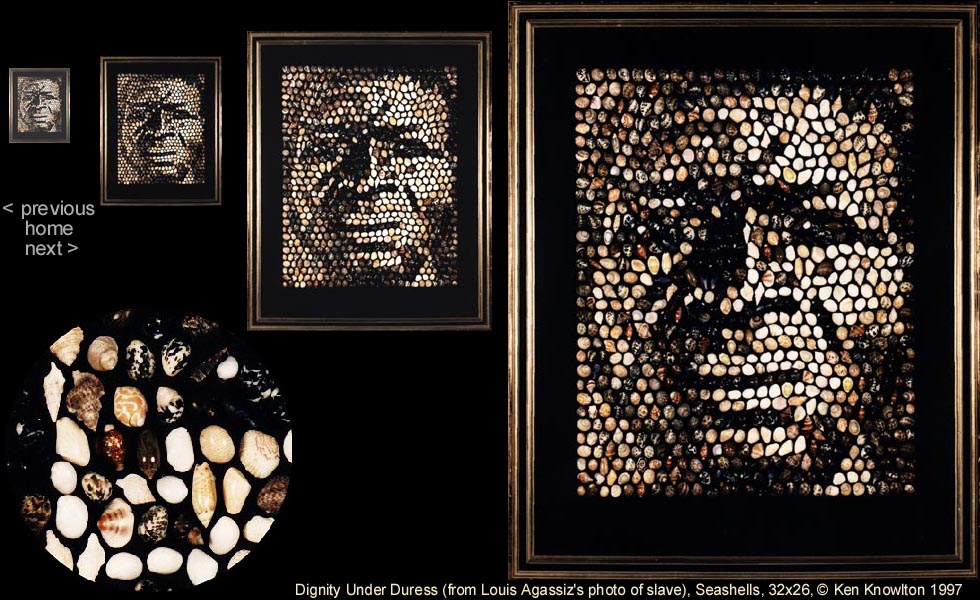

Their significance was immediately apparent. They were some of the earliest known images of American slaves, milestones in the histories of race and photography. They were also visually striking. Many of their subjects stared at the camera with undeniable dignity despite their humiliating circumstances.

“Agassiz was trying to dehumanize these subjects in an anthropological or medical way,” said John Stauffer, chairman of Harvard’s Program in the History of American Civilization, who plans to mount his own exhibit on the images within the next year. “The rich irony is, what comes through is these individuals’ humanity.”

Yet the images are, no doubt, disturbing. Displaying them widely, some believe, may come with a price.

“These are images that were meant to denigrate people,” said Irmscher, who chose to show only one of them in his new book. “I am deeply appreciative of the efforts to expose Agassiz’ motives, but there’s a thin line between documenting the extent of his racism and perpetuating it by making these photographs public again.”

Although Peabody curators have spent years carefully weighing how widely the images should be distributed, there is little reason to think that Harvard has tried to shield them from public view. The Peabody has allowed them to be reproduced in photography textbooks and academic papers, on the Harvard library website, and in at least two foreign-language books that are sharply critical of Agassiz.

All of which raises the question of why the Swiss group cannot show them.

Jessica Desany Ganong, the imaging services coordinator of the Peabody, said in an e-mail to the Globe that the museum’s curators had made their decision “based on a current blanket museum policy that covers all images of nudes in the Museum’s collection taken by any photographer at any period in an exploitative manner (which includes other images besides those commissioned by Agassiz). This policy does not focus on Agassiz or his beliefs.”

But Fässler, the leader of the Swiss group, said the Peabody had told him via an e-mail, obtained by the Globe, only that the images were considered “sensitive.”

Louis Agassiz statue after 1906 quake

Louis Agassiz statue after 1906 quake

Fässler also pointed to another e-mail from an assistant at the Harvard Art Museums, a separate entity, which the Swiss approached for permission to reproduce a painted portrait of Agassiz. That museum, too, denied the group permission, at least at first. In April, an employee of the Harvard Art Museums sent the Swiss an e-mail saying that its curators found “some of the language in your exhibition materials, although interesting, aggressive towards Agassiz, who was a very influential figure at Harvard.”

After the Swiss complained, Daron Manoogian, director of communications for the Harvard Art Museums, intervened. The Swiss group will be able to use the portrait, after all.

The April e-mail, Manoogian said, was sent in error by “a very new, temporary employee” who, working with a curatorial assistant while two senior curators were away, “was acting in good faith but made the wrong decision.” Harvard, he added, “always errs on the side of scholarship. And we don’t make determinations about what that scholarship is.”

But Fässler remains infuriated by the Peabody’s continuing refusal of permission. So his exhibit will show not only silhouettes it has created based on the images, but also the relevant e-mail exchanges with the employees of both Harvard museums — which, even if they were sent partly in error, give the exhibit an extra punch.

“Sometimes,” Fässler said, “the ‘other side’ just makes the best mistakes.” (source:

The Boston Globe)