South Jersey Heritage: A Social, Economic and Cultural History - R. Craig Koedel --"CHAPTER EIGHT: The Fight Against Slavery" -- Black slavery, although less extensive in South Jersey than elsewhere in the state, arrived with the earliest of the English settlers. In the 1676 Concessions and Agreements the term "slave" was omitted, but the institution was recognized in that every freeman taking up lands in West Jersey was to be allotted additional acreage for every "servant that he or she should carry or send." The holding of Negro slaves had long been customary among English landowners and it was the expectation, indeed the wish, of the framers of West Jersey that the practice be continued in the New World.

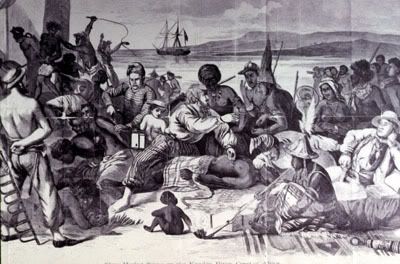

Queen Anne instructed Lord Cornbury, the first royal governor, to report on "the present number of . . . . Masters as Servants, free and unfree, and of the slaves in our said Province." The governor was told, moreover, to be prompt in paying the Royal African Company for their human merchandise in order that the province "may have a constant and sufficient supply of Merchantable Negroes, at moderate rates. . ." He was advised, however, to seek legislation by the provincial government restraining inhuman severity towards slaves and imposing capital punishment upon any master or overseer guilty of "the wilful killing of Indians and Negroes," Their conversion to the Christian religion was to be encouraged.

An act passed by the provincial assembly in 1713 authorized the return of runaway slaves, stipulating that the expenses for such be borne by the owners, and detailed the punishments to be meted out to slaves convicted of crimes.

Slaves were deprived, by the same act, of the right to own property. Lest they become a burden to society, freed slaves were to be given twenty pounds; otherwise the manumission would be nullified. By a later act, of 1752, tavern keepers were forbidden to sell "strong liquors" to slaves. Persons in bondage were denied the right to assemble in groups of more than five, or to be away from the master’s house after nine at night, except when meeting or traveling on the master’s business.

The slave population of the counties of Gloucester, Salem, and Cape May stood at 348 in 1737. Eight years later, 441 blacks were being held in bondage in the same counties, their numbers having increased by 27%. During the same period, the total population of the area grew by less than 14%. At mid-18th century, slavery was a thriving institution in South Jersey, as it was elsewhere in the colony.

Pennsylvania slave traders transferred their operation to New Jersey in 1761, when the Quaker colony voted to impose a fifteen-pound duty on the business. African Negroes were auctioned off on blocks at Cooper’s Ferry from that year until 1765. Four years later, in 1769, New Jersey followed Pennsylvania in assessing a fifteen-pound duty on the purchase of black slaves. Simultaneously, the price of African Negroes rose to a level beyond the financial resources of New Jersey buyers, and the overseas slave trade in the state came to an end.

Map of Camden, New Jersey

With the importing of slaves from Africa a thing of the past, cries against the inhumanity of the very institution of slavery began to be raised, as conscientious whites called for abolition during the years of the Revolution, and following. Nothing contrary to the practice of keeping slaves was written into the first state constitution, adopted on July 2, 1776. However, ten years afterward the state passed an act, the preamble of which betrayed a growing uneasiness regarding its morality: ". . . the principles of justice and humanity require that the barbarous custom of bringing the unoffending Africans from their native country and connections into a state of slavery ought to be discontinued, and as soon as possible prevented . . ."

The reluctance of the state to proceed with abolition notwithstanding, the 1786 law tried to ameliorate the predicament of the enslaved. It delineated the circumstances under which a slave could be brought into New Jersey, defined requirements concerning manumission, and authorized the indictment of persons suspected of the abuse and inhumane treatment of their slaves. By a 1788 law, masters were required to instruct their young slaves in reading and writing. The same law provided for the confiscation of any vessel within New Jersey fitted out as a slaver. An act summarizing and codifying the state’s slavery laws followed in 1798, though outright abolition of the institution was still rejected.

Human bondage existed in South Jersey at the turn of the 19th century, but its incidence was declining markedly. Whereas the slave population in the southern counties increased only 42% between 1745 and 1790, to a total of 624 in the last year, the population grew by 200%. Ten years later, the population having continued to climb, the number of slaves had decreased to 319. Contrasted with this noticeable reduction in the southern counties was the statewide increase of the slave population, during the same decade, in an amount just one short of 1000.

It is significant that the formerly Quaker counties were taking the lead in the gradual destruction of slavery as an institution in New Jersey at the approach of the 19th century. That the Quakers were among those who brought the institution to the New World is shown in directives of the Society of Friends in 1696, in which members were cautioned against the further purchase of slaves. The "Negroes" they already had were to be restrained from "loose and lewd living" and provided with opportunities for religious worship. Nevertheless, as early as 1688 a minority of American Quakers was agitating against slavery. At mid-18th century, the issue came to the serious attention of the Society of Friends, among whom John Woolman, in particular, in his superb essays and oral declamations eloquently denounced the enslavement of the black race. He, with three others, was appointed in 1758 to counsel with slaveowning Quakers about their Christian obligation to free those whom they held in bondage.

Although some progress was made, their efforts were not at once totally successful. As late as 1777, the Haddonfield meeting reported that twenty-eight slaves had been manumitted within their bounds, while a sizeable list of persons not complying was attached to the report. A similar account was submitted regarding Woodbury. Salem Quakers, too, were still in the process of freeing their slaves in 1777. After Woolman’s death, his cousin, John Hunt, pursued the good work of the Quaker saint. By September, 1788, partly because of his labors, the Haddonfield meeting was able to announce that "No negroes [are] held in bondage among us."

Sometimes the influence of New Jersey Quakers in discouraging slavery, other than among their own membership, is minimized. Nonetheless, it was a group of Quakers who petitioned the provincial legislature in 1775 to enact laws abolishing the institution. Even though unable to move the representatives toward this action, the Quakers set the example. By 1800, the residents of Burlington, Gloucester, and Salem Counties owned only 3% of the blacks still being held within New Jersey, whereas they comprised 23% of the state’s population.

Gradual abolition was enacted, at last, on February 15, 1804 in a bill which declared free every child born of a slave within the state after July 4, 1805. However, a boy was to remain the servant of his mother’s owner, or his heirs, until the age of twenty-five. A girl was to retain that status until she reached twenty-one. A master could forfeit his right of ownership if he chose, but he was required to support the child for one year, after which the child would become the ward of the county. A later law forbade the removal of a slave from New Jersey for the purpose of changing his place of residence, without the slave’s consent, or, in the case of a minor, the consent of the parents. A supplement imposed a penalty of a fine and imprisonment upon any violator of this law, and the slave in question was to be set free. Residents of New Jersey were forbidden to sell any of their slaves to non-residents.

The manumission of black slaves did not mean that Negroes had been accepted as equals by South Jersey whites, for free blacks also were legally and socially restricted. By judicial decision, for example, a Negro was to be deemed a slave unless he could prove that he was free. This ruling was pronounced in 1795 and again in 1821, when the chief justice said in his charge, "in New Jersey,...all black men, in contemplation of the law, are prima facie slaves, and are to be dealt with as such. The colour of the man [i.e. the plaintiff’s slave] was sufficient evidence that he was a slave until the contrary appeared. All our laws upon this subject are founded upon this principle, and all men of this colour are to be dealt with on this principle." Some Quaker masters, upon freeing their slaves, granted them tracts of land, which were then held in trust by the grantors, because titles of free blacks were not always recognized. The 1844 Constitution of the State of New Jersey limited the vote to white males.

An attempt in 1824 to relocate free blacks on the island of Haiti met with failure. A number of them having left for the Caribbean from Port Elizabeth, in Cumberland County, returned in a short time to their former homes and jobs.

Whereas the number of slaves in South Jersey declined steadily after 1790, almost reaching the point of nonexistence by 1830, the percentage of free blacks within the population was mounting. In 1820, the slaves in the four southern counties numbered 100, the free blacks 2875. There were only ten slaves in the same area in 1830, while the free black population stood at 3971. Of these, Gloucester County had the largest number. Salem County had the highest percentage of blacks within the total population; ten percent of the county’s residents were Negroes. In that year (1830), Gloucester County had four slaves and Salem County one. Before the Revolution, the total black population, slave and free, of any southern county never reached six percent.

Two factors may help to account for this changing pattern: the emigration of white farmers to the western lands after the Revolution and the opening up of New Jersey as a haven for fugitive slaves from Delaware, Maryland, and the South. Before 1826, slaves fleeing from southern masters could hope for little refuge in New Jersey, where bounty hunters hotly pursued the rewards offered for the capture of runaways. At the end of 1826, the incentive for tracking down fugitives was withdrawn when an act terminating the giving of rewards for their capture was passed by the legislature on December 26. Furthermore, the act so circumscribed the procedure for the apprehending and return of runaways that, in the southern counties, where many residents were inclined to give aid to escaping blacks, the Underground Railroad to Canada could operate more openly, and hundreds of blacks chose to end their flight and settle in the relative peace and security of South Jersey.

Under the 1826 law, to take up an alleged fugitive, the owner or his agent was required to request a judge of the common pleas or a justice of the peace to issue a warrant for the fugitive’s arrest. Moreover, proof of ownership had to be shown before the justice was permitted to release the fugitive for return to his home state or territory. To seize or remove alleged runaways without the necessary warrants was made a misdemeanor. A later supplement provided that any case involving a fugitive slave must be tried before three judges, and guaranteed alleged fugitives the right to trial by jury.

The Underground Railroad, carefully planned routes for southern slaves fleeing from their masters, operated in New Jersey. Each route had a chain of "stations," hiding places such as a barn, where fugitives paused during daylight hours for food and shelter before being transported, by night, to the next stop. Quakers, ministers, and other whites, and free blacks acted as "station masters." "Conductors" escorted the runaways from station to station.

Principal way stations of the Underground Railroad across South Jersey were located at Camden, Salem, and Greenwich. The most commonly used route from the South traversed Maryland and Delaware to Philadelphia, where the fugitives were sequestered by a freed slave, William Still, until passage could be arranged across the river to Camden. The station master at the New Jersey city was the Rev. T. C. Oliver, who provided sustenance and cover for the fleeing slaves, while they paused before starting their journey across the New Jersey corridor to New York City, and northward. Fugitives who gathered at Dover, Delaware, were boated across the river to the relative safety of the Jersey shore at Salem, where Abigail Goodwin was in charge. An unknown number of them relinquished the opportunity to escape to Canada, choosing instead to take their chances at planting new homes in Salem County. Those who elected to go on were routed through Woodbury to Bordentown, then over the Railroad’s main line to New York.

At Greenwich, escape boats flashing blue and yellow signal lights were met by station master Levin Bond, or one of the Sheppards, or Stanfords, after which conductors guided the fleeing slaves through Swedesboro and Woodbury to Burlington County, where they picked up the route to New York. Homes at Town Bank and Cape May Court House are said to have been havens for slaves escaping to the North.

Most of South Jersey lies below the Mason and Dixon Line, the traditional line of demarcation between northern and southern United States. Given its location, it would be expected that on any issue separating the two halves of the nation, South Jersey would be inclined toward a Southern viewpoint. Such was not the case, however, in 1860. Whatever pro-Southern sentiment there may have been in the southern counties did not surface, or was not of a vitality to sway majority opinion, in the crises that precipitated the Civil War.

Lincoln carried all but one (Camden) of the six counties of South Jersey in the 1860 election, whereas all but four of the counties to the north of the Mullica River, where the majority was contemptuous of the "Black Republican," voted for his opponents. Their heavier popular and electoral weight put New Jersey in the Democrat column in that presidential race. The state’s pro-Southern strength did not lie in the southern counties.

New Jersey was at one, however, in its dedication to the principle that the Union must be preserved at all costs. Although some would have preferred peace on the South’s terms to the suffering and economic dislocations of war, the state clearly supported the North, and the nation’s new leader, when the Union was confronted with the prospect of Southern secession. Triggered by the bombardment and capture of Fort Sumter on April 12-13, 1861, the southern counties were joined by those to the north, Democrats and Republicans, in giving way to a patriotic frenzy of flag waving, drum beating, and speechmaking. Resolutions to stand by the nation and her colors were adopted at every village, town, and crossroads.

Northern confidence in the ease and quickness of victory was summarized in a facile declaration by a South Jersey congressman at Bridgeton, in which he said, "This rebellion could easily be put down by a few women with broomsticks." Nonetheless, New Jersey quickly sent a fully organized and equipped brigade of four regiments to Washington, where they marched through the streets on May 6. As yet, there were no battles to be fought, so the Jersey troops were set to erecting a fortification around the city.

The battles came--Bull Run, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and on and on. In all, 88,000 New Jerseymen took up arms in the Civil War. More than 6300 of them, enlisted men and officers, perished of wounds or disease.

Called up for duty, South Jersey recruits bound for the battlefields of Virginia gathered at their county seats, where they were mustered into the service. By wagon, then train, they rode through Woodbury and Camden to the embarkation center at Beverly, a town on the Delaware River in Burlington County. Formed into regiments at Beverly, they departed by steamer for Philadelphia, to proceed therefrom by train to Baltimore and Washington. The Twelfth Regiment New Jersey Volunteers was stationed at Woodbury’s Fort Stockton, the largest Civil War encampment in South Jersey, until their troops joined the Army of the Potomac.

Early in the war, preparations were undertaken to protect South Jersey’s bay and ocean shorelines against Confederate attack. A telegraph line to Cape May was made operational; a maritime guard was posted along the coast; and Fort Delaware, on Pea Patch Island offshore from Salem County, was garrisoned to prevent any possible Confederate move upriver to Philadelphia. However, no Civil War battle or skirmish was fought on New Jersey soil, nor did a naval engagement of the war take place on the Delaware.

While the garrison on Pea Patch Island served to discourage any attempt at a seaborne assault on Philadelphia, it was used as well as a Northern prison. On this marshy island of 178 acres, in barracks built to accommodate 2000 men, by the summer of 1863 more than 12,500 Southern prisoners of war were suffering unspeakable horrors of brutality, malnutrition, and disease. An epidemic of cholera took more than 2000 lives; more than 700 others died from neglect and illness. Their bodies were interred at Finn’s Point, in Salem County, near the site where Johan Printz had built Fort Elfsborg.

President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 angered many in New Jersey who, although willing to defend the Union with their last drop of blood, felt that Negro slavery was an internal matter to be dealt with by each state as its people saw fit. When the war was over, a majority of the representatives at Trenton had not yet changed their minds on the subject, and so did not immediately ratify the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, the article which freed all slaves within the nation. After the amendment became federal law, in 1865, by ratification of the necessary three-fourths of the states, New Jersey concurred. As it applied to South Jersey, however, the issue was academic, for slavery had disappeared altogether from the southern counties before 1860. (source: West New Jersey)