As reported by the

BBC "Slavery and the 'Scramble for Africa'" by Dr Saul David on 17 February 2011 -- What were the motives behind the European colonization of Africa at the end of the 19th century? Did the stamping out of slavery really play a part?

European colonisation

Until the 19th century, Britain and the other European powers confined their imperial ambitions in Africa to the odd coastal outpost from which they could exert their economic and military influence. British activity on the West African coast was centred around the lucrative slave trade.

Between 1562 and 1807, when the slave trade was abolished, British ships carried up to three million people into slavery in the Americas. In total, European ships took more than 11 million people into slavery from the West African coast, and European traders grew rich on the profits while the population of Africa's west coast was devastated.

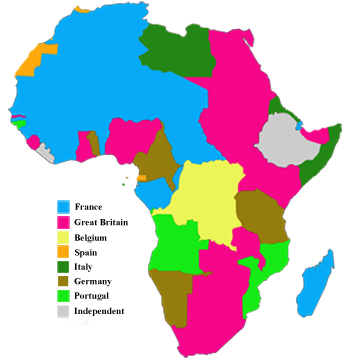

As late as the 1870s, only 10% of the continent was under direct European control, with Algeria held by France, the Cape Colony and Natal (both in modern South Africa) by Britain, and Angola by Portugal. And yet by 1900, European nations had added almost 10 million square miles of Africa - one-fifth of the land mass of the globe - to their overseas colonial possessions. Europeans ruled more than 90% of the African continent.

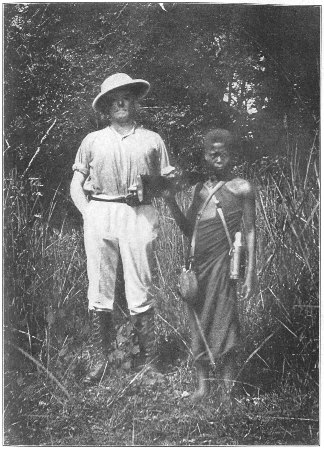

One of the chief justifications for this so-called 'scramble for Africa' was a desire to stamp out slavery once and for all. Shortly before his death in May 1873 at Ilala in central Africa, the celebrated missionary-explorer David Livingstone had called for a worldwide crusade to defeat the slave trade controlled by Arabs in East Africa, that was laying waste the heart of the continent.

The only way to liberate Africa, believed Livingstone, was to introduce the 'three Cs': commerce, Christianity and civilization.

The Berlin Conference-- This was a period in history when few Europeans doubted their innate superiority over the 'lesser' races of the world.

The theory that all the peoples of Europe belonged to one white race which originated in the Caucasus (hence the term 'Caucasian') was first postulated at the turn of the 19th century by a German professor of ethnology called Johann Blumenbach.

Blumenbach's colour-coded classification of races - white, brown, yellow, black and red - was later refined by a French ethnologist, Joseph-Arthur Gobineau, to include a complete racial hierarchy with white-skinned people of European origin at the top.

Britons like Livingstone felt they had a duty to 'civilise' Africa.

Such pseudo-scientific theories were widely accepted at the time and motivated Britons like Livingstone to feel they had a duty to 'civilise' Africa.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, convened by Otto von Bismarck to discuss the future of Africa, had the stamping out slavery high on the agenda. The Berlin Act of 1885, signed by the 13 European powers attending the conference, included a resolution to 'help in suppressing slavery'.

In truth, the strategic and economic objectives of the colonial powers, such as protecting old markets and exploiting new ones, were far more important.

The Berlin Conference began the process of carving up Africa, paying no attention to local culture or ethnic groups, and leaving people from the same tribe on separate sides of European-imposed borders.

British interests

Britain was primarily concerned with maintaining its lines of communication with India, hence its interest in Egypt and South Africa. But once these two areas were secure, imperialist adventurers like Cecil Rhodes encouraged the acquisition of further territory with the intention of establishing a Cape-to-Cairo railway.

Britain was also interested in the commercial potential of mineral-rich territories like the Transvaal, where gold was discovered in the mid-1880s, and in preventing other European powers, particularly Germany and France, from muscling into areas they considered within their 'sphere of influence'.

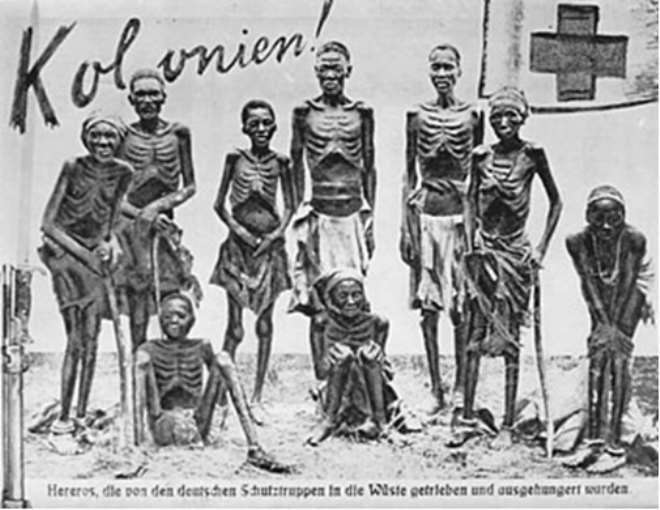

Tens of thousands of Herero men, women and children fell victim to von Trotha's infamous extermination order.

As a result, during the last 20 years of the 19th century, Britain occupied or annexed Egypt, the Sudan, British East Africa (Kenya and Uganda), British Somaliland, Southern and Northern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe and Zambia), Bechuanaland (Botswana), Orange Free State and the Transvaal (South Africa), Gambia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, British Gold Coast (Ghana) and Nyasaland (Malawi). These countries accounted for more than 30% of Africa's population.

The other chief colonisers were France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

Germany had only been unified in 1871 and so was a late starter in imperial terms. Its first acquisition in 1884 was German South-West Africa (Namibia), which at the time was peopled by two semi-nomadic tribes, the Herero of the arid central plateau and the Nama of the still more arid steppes to the south.

When the two tribes went to war over cattle grazing, German traders and missionaries persuaded their government to intervene and fill the political vacuum.

A later Herero rebellion in 1904, provoked by the brutality of the German settlers, was put down by General Lothar von Trotha with savage efficiency, and tens of thousands of Herero men, women and children fell victim to his infamous 'Vernichtungsbefehl' (extermination order).

'Spirit of Berlin'

The philanthropic 'spirit of Berlin', however, was not entirely hollow. Once it became known that slavery was alive and well in the Congo, which was run as a personal fiefdom of Leopold, King of Belgium, an international anti-slavery conference was held in Brussels in 1889-1890.

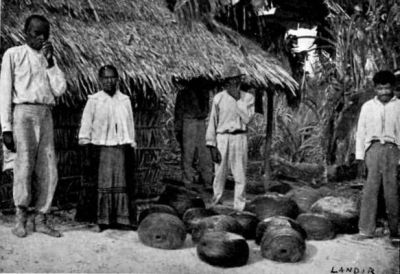

By taking the women of Congolese villages hostage, Leopold had turned the men into forced labourers.

The man who exposed the existence of slavery in Leopold's Congo was a French missionary to Africa called Cardinal Charles Lavigerie. During a sermon at St Sulpice in Paris in 1888, Lavigerie had shocked his audience by describing the horrors of the Congo slave trade: villages surrounded and burnt; men captured and yoked together; women and children penned like cattle in the slave markets.

The upshot of the Brussels conference was that Leopold cynically agreed to stamp out Arab slavery in return for the right to tax imports. He thereby overturned one of the key resolutions of the Act of Berlin, which had guaranteed free trade for the region.

But while Leopold made all the right noises, his agents in the Congo used forced labour (slaves in all but name) to extract rubber, his single most profitable export. By 1902, rubber sales had risen 15 times in eight years, and were valued at 41 million francs (£1.64 million).

By taking the women of Congolese villages hostage, Leopold had turned the men into forced labourers, with a monthly quota of wild rubber to collect from the rain forest. The system was harsh. Many hostages starved to death and many male forced labourers were worked to death.

More people were killed as rebellions were brutally crushed. Demographers today estimate that the population of the Congo fell roughly by half over the 40-year period beginning in around 1880.

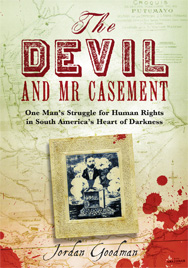

The truth behind the Congo's rubber trade - 'legalised robbery enforced by violence' - was finally exposed by Edmond Morel, an Anglo-French ex-shipping clerk, who wrote a series of accusatory articles in 'The Speaker' in 1900.

By arguing that Leopold's illegal state monopoly was robbing British merchants as well as African peasants, Morel was able to enlist the support of both businessmen and humanitarians. A British consul, Roger Casement, was sent to investigate, and the publication of his damning report in 1904 was, for Leopold, the beginning of the end.

In 1908, in return for £3.8 million, Leopold handed over control of the Congo to the Belgian state. But even then, the forced labour system continued. It took a different form during World War One, when tens of thousands of Congolese were conscripted as porters for the Belgian army.

The forced labour system significantly changed only in the early 1920s, when Belgian colonial authorities realised the population was dropping so rapidly that they soon might have no labour force left.

An end to African slavery?

The signatories of the General Act of the Brussels Conference of 1889-1890 had declared an intention to put an end to the traffic of African slaves. This was extended, by the Convention of St-Germain-en-Laye in 1919, to include the complete suppression of slavery in all its forms and of the slave trade by land and sea.

Under all the colonial powers, forced labour remained in place into the 1940s.

In September 1926, the International Slavery Convention was signed at Geneva under the auspices of the League of Nations 'to find a means of giving practical effect throughout the world to such intentions'.

It defined a slave as a 'person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised', and undertook 'to bring about, progressively and as soon as possible, the complete abolition of slavery in all its forms'.

But this was never applied against the practice of forced labour in colonial Africa, for example, requiring a village to provide men to work on roads and other public works. Under all the colonial powers, forced labour of one kind or another remained in place into the 1940s, and the imposition of taxes forced people into low-paid mining, industry or agribusiness jobs when they might otherwise have remained farmers.

The first practical consequence of the convention was that Ethiopia became the last African state to abolish slavery in 1932. All colonial regimes had long since done the same. Yet even today slavery is not unknown in Africa, particularly in countries such as the Sudan where law and order are often absent.

Nor have the colonists ever really gone away. White-owned businesses still dominate the mining of Africa's most valuable natural resources - particularly gold and diamonds - and in the eyes of some the continent has never stopped being plundered.

(source:

BBC)