Was Britain 'built on the blood of slaves'?

On June 2nd (Tuesday) a team of historians from UCL (University College London) will launch a major investigation into Britain's debt to slavery and create the first 'Encyclopaedia of British slave owners'. This online database will identify every slave-owner resident in Britain in the 1830s (when slavery was abolished) and show how slave-related wealth was put to use. It will highlight the major companies, art collections and institutions which can trace their existence back to colonial slavery in the 19th century.

The three-year project, entitled 'Legacies of British Slave Ownership', is the first comprehensive attempt to trace the impact of slave ownership on the development of modern Britain. The team, led by Professor Catherine Hall and including Dr Nick Draper and Keith McClelland, will build a systematic analysis of the economic, commercial, political, cultural, social and physical legacies of slave ownership.

"At the time of Emancipation under the 1833 Abolition Act, £20million – an enormous sum of money at that time – was paid as compensation to owners of the enslaved throughout the British colonies," explains Professor Hall. "The mechanisms set up by the British state to distribute these funds led to the creation of the first full census of colonial slave-ownership, and we've used these records to identify that over half of this compensation was paid to absentee owners and mortgagees in Britain itself. Our new study will focus on the contribution to the development of modern Britain of these men and women, their families and the firms and institutions which the slave-owners founded or financed, many of which are still identifiable in Britain today."

The study, funded by a £613,000 grant from the UK's Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), aims to produce a web-based encyclopaedia of slave ownership accessible to academic researchers and the general public. The team will co-operate with other scholars in Britain and abroad to pull together research on various aspects of slave ownership.

"The 2007 bicentenary stimulated many projects examining local and regional linkages with colonial slavery in metropolitan Britain," says Keith McClelland. "As yet, we don't have the big picture that would enable us to assess slave-ownership's national significance, but this is the project that will give us that overview."

Dr Nick Draper adds: "We're delighted to have won the support of the ERSC for a project that we believe will bring a much deeper understanding of the many ways in which slavery came home to Britain and allow us to map colonial slave-ownership on to the development of British metropolitan society." (source: EurekAlert!)

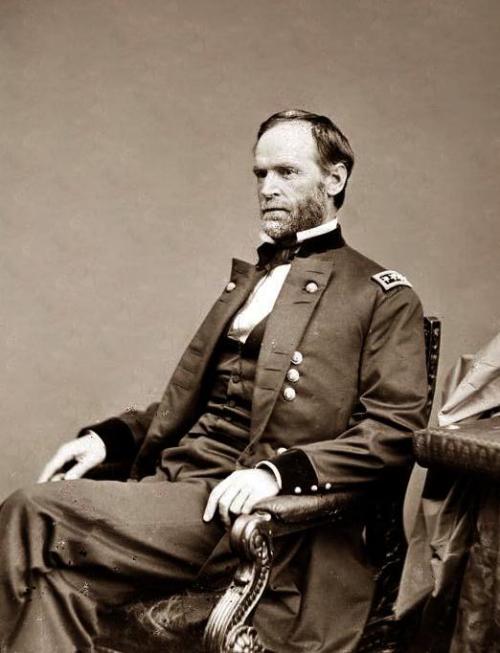

Dr Nick Draper (UCL History)

For Liverpool and Bristol much work has been done in tracing the role of the slave-trade and slavery in shaping the cities' histories, but the scale and complexity of London's growth in the 18th and 19th centuries has obscured the contribution of slavery to the formation of the modern capital. This lecture explores the evidence for the centrality of slavery in understanding how London became what we know it as today.

This lecture marks Black History Month.

What does London owe to slavery? (26 Oct 2010)